Содержание

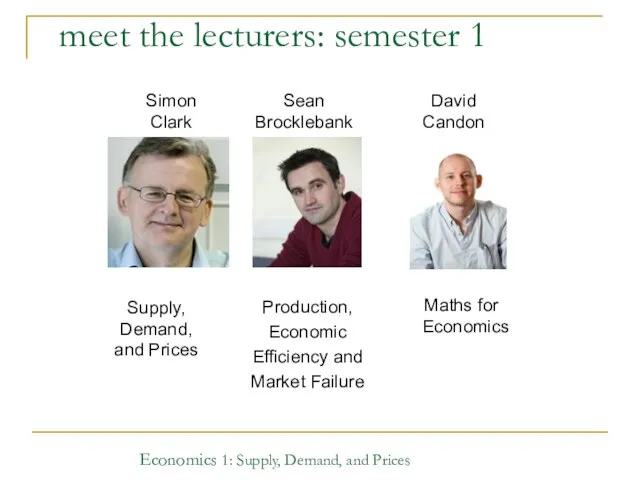

- 2. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices meet the lecturers: semester 1 Simon Clark Supply, Demand, and

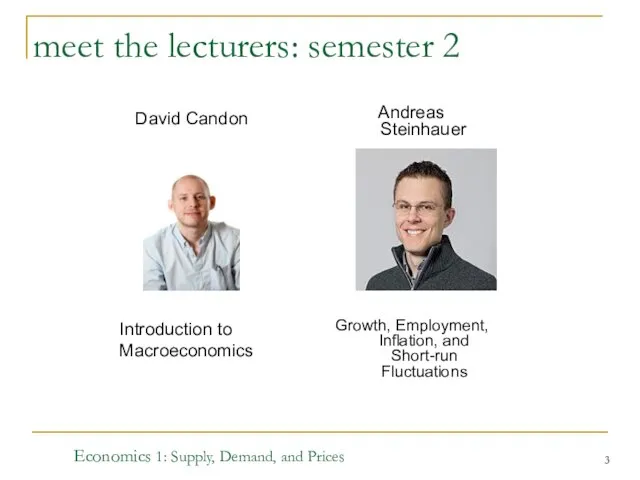

- 3. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices meet the lecturers: semester 2 Growth, Employment, Inflation, and Short-run

- 4. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices Before we start… Is Economics 1 the right course for

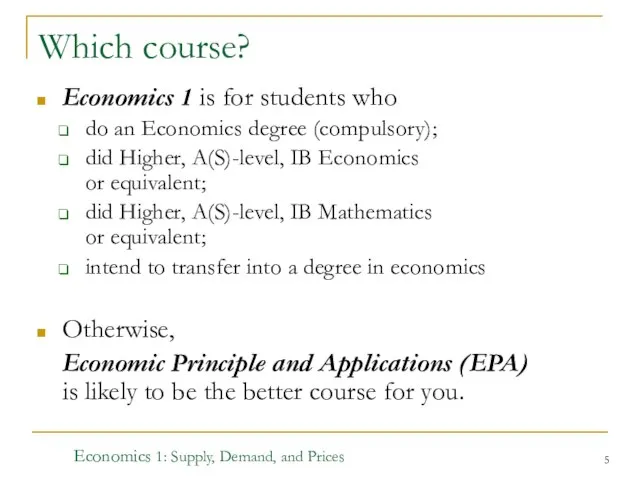

- 5. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices Which course? Economics 1 is for students who do an

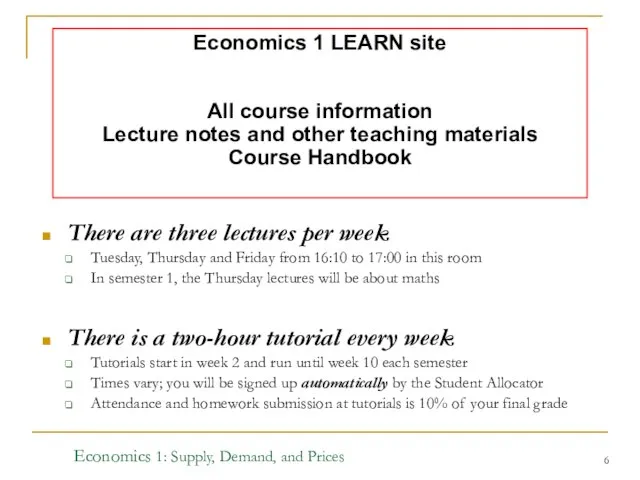

- 6. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices There are three lectures per week Tuesday, Thursday and Friday

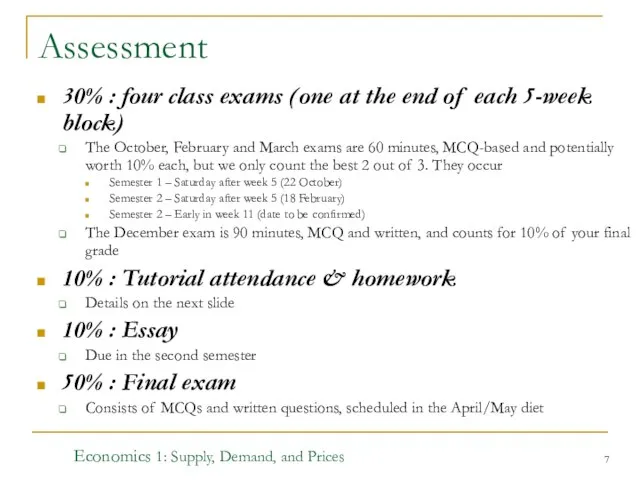

- 7. Assessment 30% : four class exams (one at the end of each 5-week block) The October,

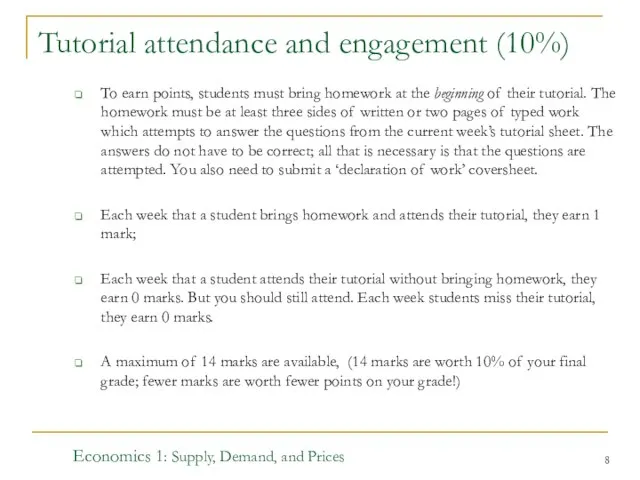

- 8. Tutorial attendance and engagement (10%) To earn points, students must bring homework at the beginning of

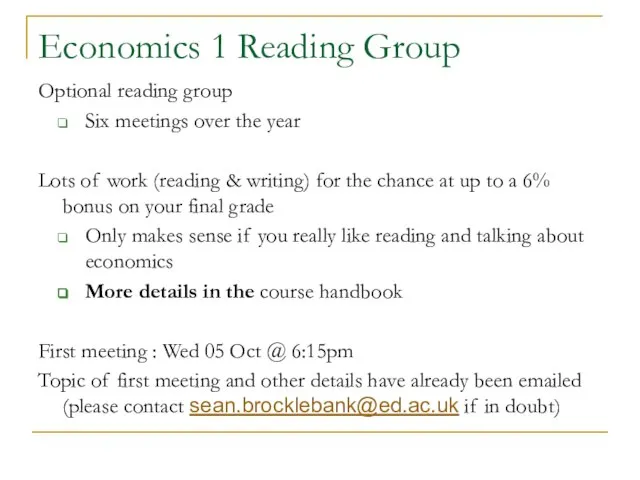

- 9. Economics 1 Reading Group Optional reading group Six meetings over the year Lots of work (reading

- 10. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices Textbooks There are two core textbooks One for micro in

- 11. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices Math textbook There is a suggested math text Most of

- 12. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices Helpdesks Twice-weekly Economics 1-only helpdesk staffed by some of the

- 13. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices maths in economics: why? Many economic magnitudes are inherently numerical

- 14. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices what maths do we use in Economics 1? basic algebra

- 15. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices Outline of weeks 1 - 5 Frank & Cartwright Thinking

- 16. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices some things to note these lectures will not be repeating

- 17. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices to illustrate the economic approach, consider some interesting problems: the

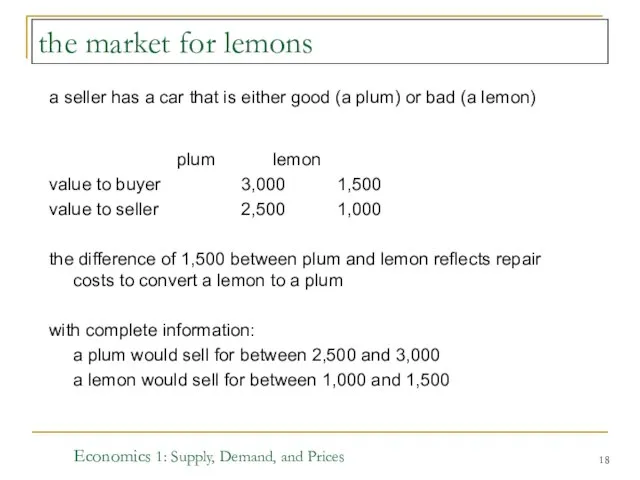

- 18. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices the market for lemons a seller has a car that

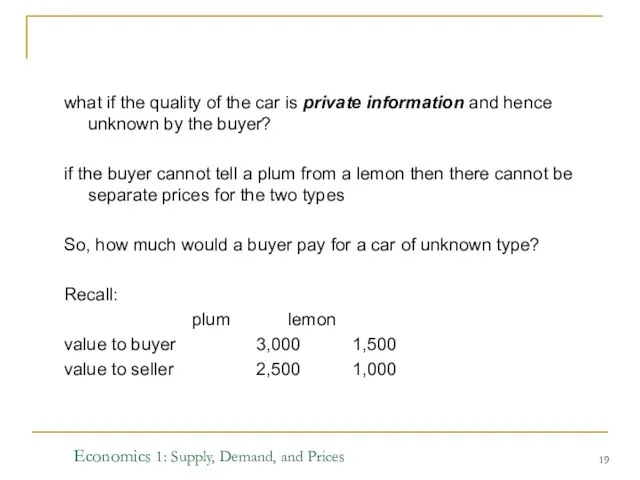

- 19. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices what if the quality of the car is private information

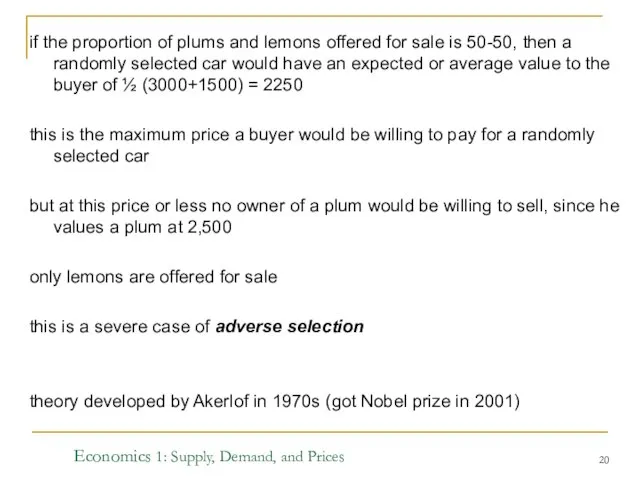

- 20. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices if the proportion of plums and lemons offered for sale

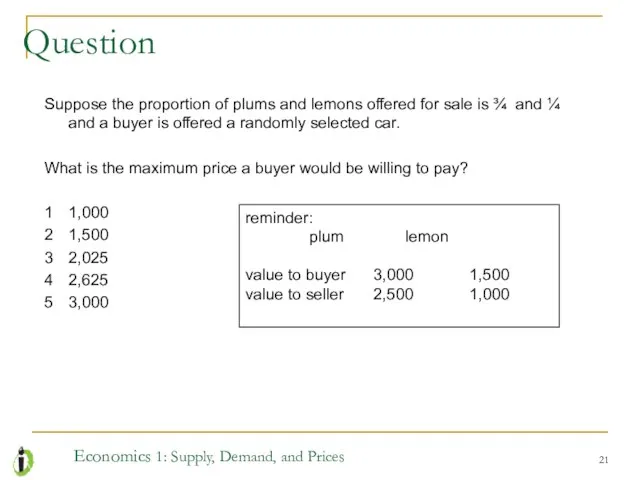

- 21. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices Suppose the proportion of plums and lemons offered for sale

- 22. if the proportion of plums and lemons offered for sale is ¾ and ¼ , then

- 23. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices market failure if the maximum price a buyer is willing

- 24. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices the ubiquity of (possible) adverse selection insurance markets careful/reckless drivers

- 25. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices adverse selection and liquidity banks selling bundles of debt (CDOs)

- 26. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices signalling: one way to overcome adverse selection an informative signal

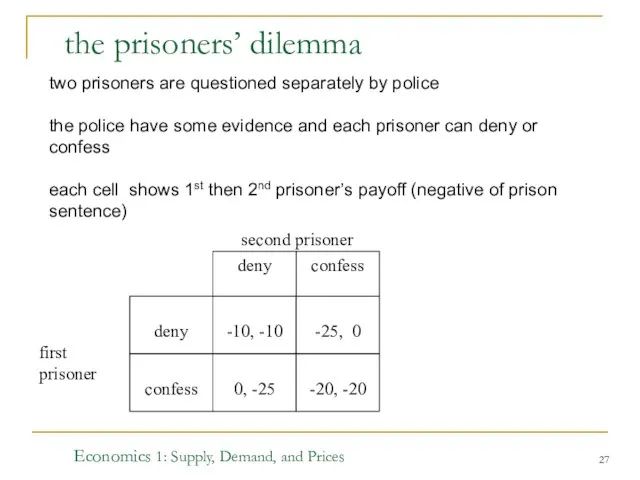

- 27. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices the prisoners’ dilemma deny -10, -10 0, -25 confess -25,

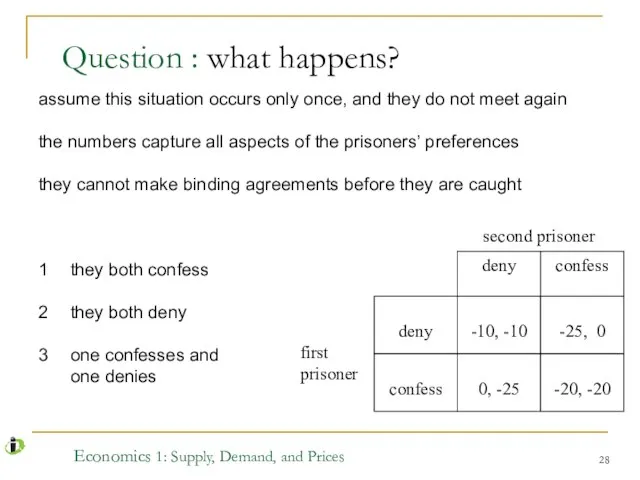

- 28. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices Question : what happens? deny -10, -10 0, -25 confess

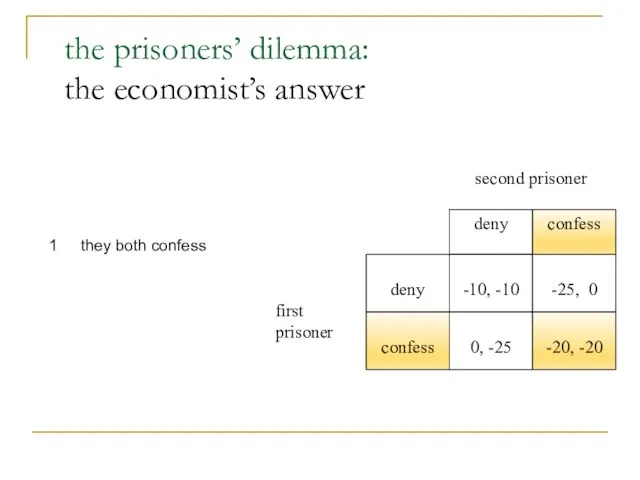

- 29. the prisoners’ dilemma: the economist’s answer deny -10, -10 0, -25 confess -25, 0 -20, -20

- 30. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices the payoffs in the prisoners dilemma have a very particular

- 31. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices the Prisoner’s dilemma is a metaphor for a wide range

- 32. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices What if the situation is repeated? Does cooperation emerge? How

- 33. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices ice cream wars 2 ice-cream sellers simultaneously choose a location

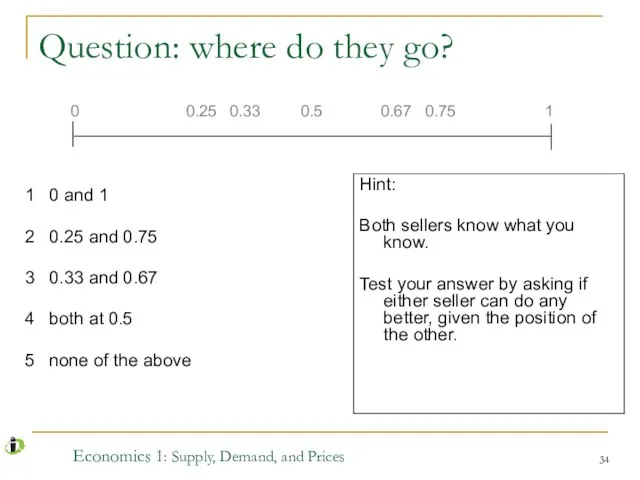

- 34. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices Question: where do they go? 1 0 and 1 2

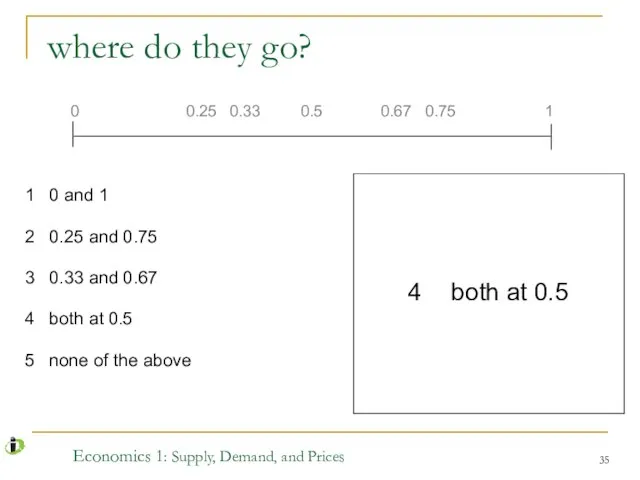

- 35. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices where do they go? 1 0 and 1 2 0.25

- 36. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices again, this can be seen as a metaphor for many

- 37. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices some interesting extensions to consider what if there are 3

- 38. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices the demand for things without a market a common problem

- 39. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices hedonic pricing people are prepared to pay more for goods

- 40. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices using house prices a house: price reflects size, style, number

- 41. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices house prices and school quality Cheshire and Sheppard, (Economic Journal

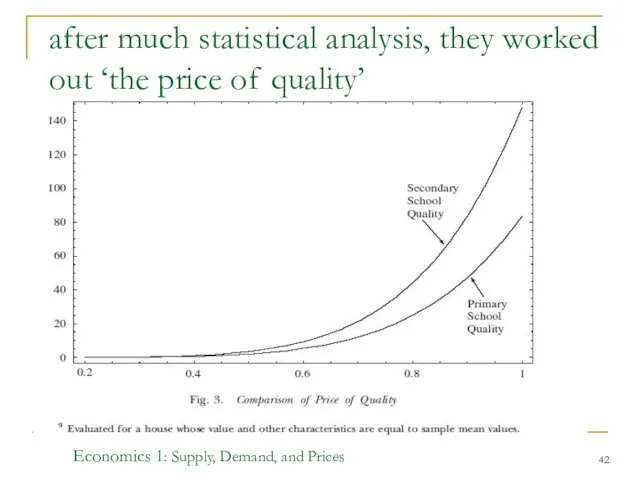

- 42. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices after much statistical analysis, they worked out ‘the price of

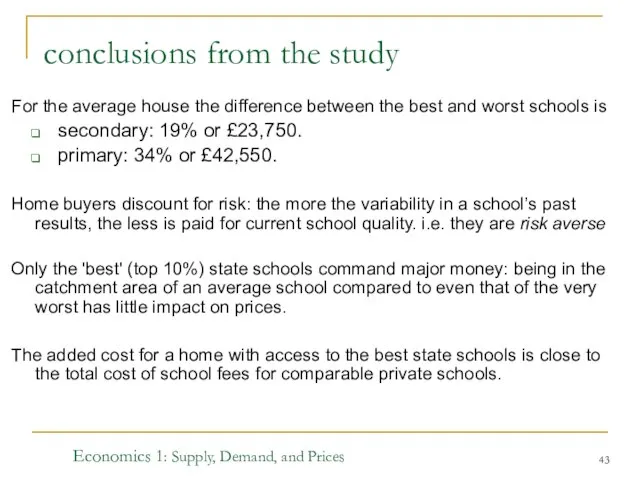

- 43. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices conclusions from the study For the average house the difference

- 44. Economics 1: Supply, Demand, and Prices conclusions from these problems simple numerical examples can be very

- 46. Скачать презентацию

Бережливое предприятие. Чем является Бережливое предприятие

Бережливое предприятие. Чем является Бережливое предприятие Три модели экономики. 9 класс

Три модели экономики. 9 класс Презентация Экспортоориентированный сектор экономики с позиций обеспечения экономической безопасности

Презентация Экспортоориентированный сектор экономики с позиций обеспечения экономической безопасности  Рыночные отношения в экономике

Рыночные отношения в экономике Глобализация и глобальные вызовы человеческой цивилизации, мировая политика

Глобализация и глобальные вызовы человеческой цивилизации, мировая политика История экономических учений. Этапы становления экономической науки

История экономических учений. Этапы становления экономической науки Міжнародна конкурентоспроможність підприємства

Міжнародна конкурентоспроможність підприємства Analiza PEST

Analiza PEST Рынок и рыночный механизм

Рынок и рыночный механизм Производство экономических благ. Издержки производства. (Тема 4)

Производство экономических благ. Издержки производства. (Тема 4) «Великая трансформация» Карла Поланьи: прошлое, настоящее, будущее

«Великая трансформация» Карла Поланьи: прошлое, настоящее, будущее Общественное производство. Блага и их классификация

Общественное производство. Блага и их классификация Барьеры входа на отраслевые рынки. (Лекция 3)

Барьеры входа на отраслевые рынки. (Лекция 3) Акция Поезд будущего: вклад представителей разных национальностей в социально-экономическое развитие и культурное наследие Дона

Акция Поезд будущего: вклад представителей разных национальностей в социально-экономическое развитие и культурное наследие Дона Управление повышением производительности труда

Управление повышением производительности труда Предмет и метод экономической теории. Понятие общественного производства

Предмет и метод экономической теории. Понятие общественного производства Соглашение о единых правилах определения страны происхождения товаров

Соглашение о единых правилах определения страны происхождения товаров Решение задач

Решение задач Экономическая социология

Экономическая социология Экономические идеи монетаризма

Экономические идеи монетаризма Префектура Канагава

Префектура Канагава Анализ безубыточности предприятия

Анализ безубыточности предприятия Профессия экономиста и как открыть свое дело. (Раздел 6)

Профессия экономиста и как открыть свое дело. (Раздел 6) Анализ и оценка инновационного развития Республики Башкортостан

Анализ и оценка инновационного развития Республики Башкортостан Механизм образования и развития кластера хозяйствующих субъектов за счет hi-tech маркетинга

Механизм образования и развития кластера хозяйствующих субъектов за счет hi-tech маркетинга Матрицы. Матричные модели в экономике,

Матрицы. Матричные модели в экономике, Фирмы в экономике

Фирмы в экономике История экономической мысли. Феномен Карла Маркса. (Лекция 3)

История экономической мысли. Феномен Карла Маркса. (Лекция 3)