- Главная

- Литература

- Georgi Dimitrov

Содержание

- 2. The Comintern: Institutions and people Dr Nikolaos Papadatos, University of Geneva Global Studies Institute Email: nikolaos.papadatos@unige.ch

- 3. INDEX 1 Georgi Dimitrov: Biography 2 Dimitrov and the Bulgarian Social Democratic Party 3 Dimitron and

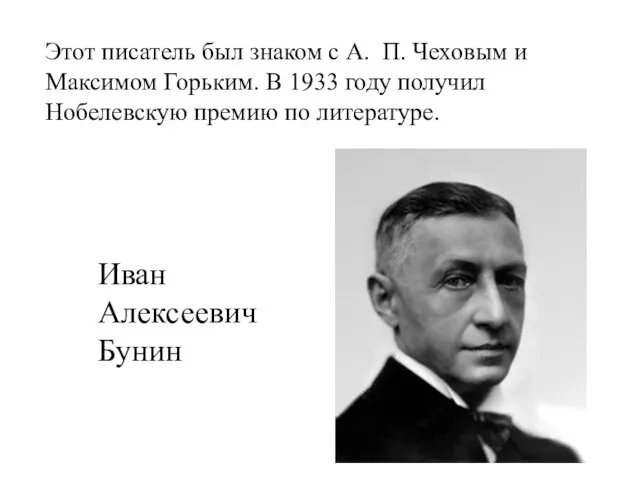

- 4. Georgi Dimitrov: Biography Georgi Dimitrov was born on 18 June 1882 (o.s.) in the village of

- 5. Macedonia was restored to the Ottomans, its Pirin area having been subdued after an uprising centered

- 6. Expelled two years later, Dimitrov then became an apprentice in the printing house of Ivan Tsutsev.

- 7. Dimitrov and the Bulgarian Social Democratic Party Dimitrov soon fell under the sway of Bulgarian Social

- 8. They where expressing mainly three different approaches: Blagoev distrusted the peasantry as a dangerous petit bourgeois

- 9. He was a secretary at the ORSS founding congress, served on its General Workers’ Council, and

- 10. Dimitron and the Balkan wars In October 1908 Bulgaria proclaimed its independence from the Ottoman Empire.

- 11. The tesniaks put up a determined campaign for peace and a Balkan federation. Dimitrov, who had

- 12. Dimitrov and the other tesniak deputies repeatedly voted against the war credits. The party joined the

- 13. Taking on the assignment, Stamboliski nevertheless formed a common cause with Blagoev, on the argument that

- 14. Dimitrov was elected to the Communist CC. The party’s program, for all its Leninist overtones, remained

- 15. Dimitrov, during the strike action of 1919–1920, he went underground with the BKP leadership. In June

- 16. In February 1921 Dimitrov finally made it to Moscow, where he met Lenin and represented the

- 17. Given Blagoev’s illness and advanced age and Kolarov’s absence in Moscow, it was Kabakchiev and Dimitrov

- 18. After news of the planned insurgency was leaked to the Tsankov government, it ordered the arrest,

- 19. Moreover, the exiled leadership of Kolarov and Dimitrov— the Foreign Committee, which soon removed to Vienna—

- 20. He represented the BKP and the Balkan Communist Federation at the Fifth Congress of the Comintern

- 21. When the Foreign Bureau of the BKP was reconstituted in Moscow, in August 1930, Dimitrov was

- 22. It was under these circumstances that the ECCI sent Dimitrov to Germany, where he acted as

- 23. More precisely: On 27 February 1933, in the midst of a violent election campaign, the Reichstag

- 24. Meanwhile, Dimitrov, two other Bulgarian Communists (Blagoi Popov and Vasil Tanev), as well as the principal

- 25. Dimitrov’s defense had four important elements. despite enormous obstacles placed in his way by the judges,

- 26. Finally, he criticized the Social Democratic leaders, Dimitrov exacted from Goebbels the admission that the Nazis

- 27. In fact, by 1 April Stalin was already encouraging him to strike against the “incorrect” views

- 28. Germany’s growing strength and aggressiveness—her denunciation of the disarmament clauses in the Versailles treaty and Hitler’s

- 29. Dimitrov stressed that fascism was a “substitution of one state form of class domination of the

- 30. Dimitrov dominated the congress so thoroughly that his elevation to the position of the Comintern’s secretary-general

- 32. Comintern: between internationalism and “nationalism” Stalin freely expressed a hierarchy of nationality preferences. He argued that

- 33. Under the circumstances, it is not unusual to encounter certain lesser Communists promoting specific national aspirations

- 34. According to one letter sent by Dimitrov to Stalin on 1 July 1934: “III. Regarding the

- 35. The decision of Comintern’s dissolution was taken as early as April 1941, when the USSR was

- 36. Dimitrov immediately took Stalin’s idea “of discontinuing the activities of the ECCI as a leadership body

- 37. The German attack on the Soviet Union appeared to give the Comintern a new lease on

- 38. The Soviet agencies were taking over parts of the Comintern operations, Stalin initially being more worries

- 39. Likewise, the Red Army Intelligence Directorate took its cut a day later. But the unkindest cut

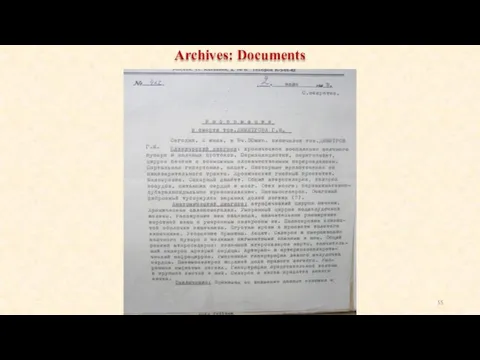

- 40. An example of this policy: Let’s see the archives “STRICTLY SECRET SUBJECT TO RETURN WITHIN 48

- 41. A group of Iranian Communists, former political prisoners, has begun to revive the Communist Party of

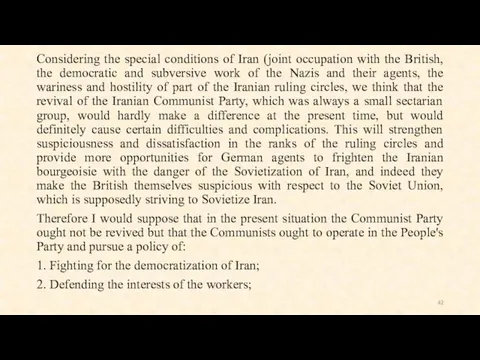

- 42. Considering the special conditions of Iran (joint occupation with the British, the democratic and subversive work

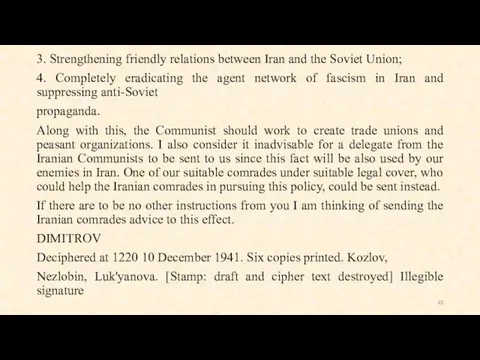

- 43. 3. Strengthening friendly relations between Iran and the Soviet Union; 4. Completely eradicating the agent network

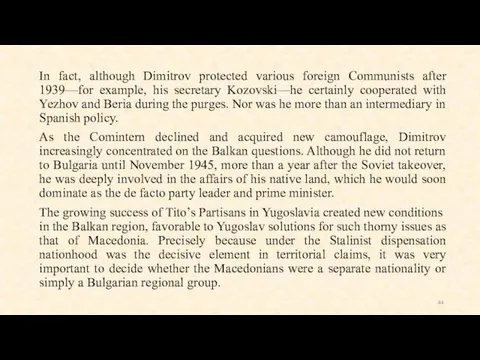

- 44. In fact, although Dimitrov protected various foreign Communists after 1939—for example, his secretary Kozovski—he certainly cooperated

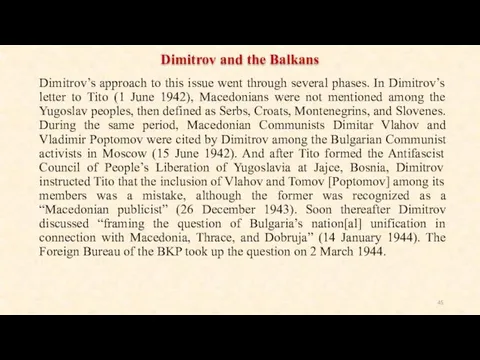

- 45. Dimitrov’s approach to this issue went through several phases. In Dimitrov’s letter to Tito (1 June

- 46. In the spring of 1944 Dimitrov maintained that the Macedonians were a populace (население), an ethnic

- 47. Tito “to explain to the Maced[onian] comrades that to all intents and purposes they ought not

- 48. They want Albania, too, and even parts of Austria and Hungary. This is unreasonable. I do

- 49. The Yugoslavs kept pursuing the exchange of Pirin Macedonia for the “western borderlands,” that is, the

- 50. The Soviet party organ Pravda publicly disavowed Dimitrov’s remarks on 29 January. Stalin now argued, albeit

- 51. Dimitrov certainly smarted from Stalin’s lashes of February 1948. This was the lowest point in his

- 52. His most obvious human failing was a curiously discreet sort of vainglory that promoted his historical

- 53. Back in Moscow in 1934, he seems to have broken up with Kiti Jovanovic´, an emigre

- 54. Georgi Dimitrov died in Moscow on 2 July 1949. He was succeeded in his duties by

- 55. Archives: Documents

- 60. Скачать презентацию

The Comintern: Institutions and people

Dr Nikolaos Papadatos, University of Geneva

Global Studies

The Comintern: Institutions and people

Dr Nikolaos Papadatos, University of Geneva

Global Studies

Email: nikolaos.papadatos@unige.ch

INDEX

1 Georgi Dimitrov: Biography

2 Dimitrov and the Bulgarian Social Democratic Party

3

INDEX

1 Georgi Dimitrov: Biography

2 Dimitrov and the Bulgarian Social Democratic Party

3

4 Dimitrov and the Komintern

5 Dimitrov in Germany

6 Dimitrov and the popular front

7 Comintern: between internationalism and nationalism

8 The last period of the Comintern

9 Dimitrov and the Balkans

10 Conclusion

11 Archives: Documents

Georgi Dimitrov: Biography

Georgi Dimitrov was born on 18 June 1882 (o.s.)

Georgi Dimitrov: Biography

Georgi Dimitrov was born on 18 June 1882 (o.s.)

Macedonia was restored to the Ottomans, its Pirin area having been

Macedonia was restored to the Ottomans, its Pirin area having been

Dimitur Mikhailov learned the hat-making trade from his brother in-law, who, like Doseva, belonged to a small group of Bulgarians that had been won over to Protestantism by American missionaries. The Protestant ethic evidently determined the life of the hatter’s family, which drew a modest income from Dimitur’s fur-hat shop. That ethic also figured in Georgi’s initial rebellion. His mother wanted him to become a pastor and in 1892 had him attend Sunday school classes at the missionary chapel.

Expelled two years later, Dimitrov then became an apprentice in the

Expelled two years later, Dimitrov then became an apprentice in the

The Dimitrovs, a family of working-class militants, seem to have had an affinity for printers’ ink. Konstantin, like his older brother Georgi, was a printer by trade and a union activist. Nikola, who moved to Russia, was a member of the Bolshevik Odessa organization and died in exile in Siberia in 1916.

Todor, an underground activist of the BKP Sofia organization, was arrested and killed by the royal police in 1925. The elder of his two sisters, Magdalina (Lina), was married to the printer Stefan Hristov Baruˇmov. The younger, Elena (Lena), followed Dimitrov into exile, where she married another exiled Bulgarian Communist, Vulko Chervenkov, Dimitrov’s successor at the helm of the BKP.

Dimitrov and the Bulgarian Social Democratic Party

Dimitrov soon fell under the

Dimitrov and the Bulgarian Social Democratic Party

Dimitrov soon fell under the

The Bulgarian Social Democratic Party, established in 1901, soon became a battlefield for fractional interests. The pursuit of purely proletarian class politics was difficult in an agrarian country whose margin of industrial workers would rise to no more than twenty thousand by 1909.

The two factions of the party: Dimitur Blagoev’s (tesniaks) against the (shiroki) led by Yanko Sakuzov.

They where expressing mainly three different approaches:

Blagoev distrusted the peasantry as

They where expressing mainly three different approaches:

Blagoev distrusted the peasantry as

Blagoev opposed the idea that the trade unions could be independent of the party and pursue purely economic goals. He argued for the political nature of trade union struggle and party control.

Blagoev rejected the idea of coalitions with nonsocialist parties, including the newly formed Bulgarian Agrarian National Union (BZNS).

Dimitrov was received into the party in the spring of 1902 and from the beginning identified with the tesniak faction. Dimitrov was a delegate to the BRSDP(t.s.) congress (July 1904) at Plovdiv, where it was decided to form the party-affiliated General Federation of Trade Unions (ORSS).

He was a secretary at the ORSS founding congress, served on

He was a secretary at the ORSS founding congress, served on

Active in the tesniak operations against the “anarcho-liberals”—the party faction that resisted Blagoev’s “bureaucratic centralism”—he was arrested in the course of the Pernik miners’ strike (June–July 1906). At this time he married Ljubica (Ljuba) Ivosˇevic´ (1880–1933), a Serbian seamstress, proletarian poet, and trade union activist, whom Dimitrov met at Sliven in 1903.

Dimitron and the Balkan wars

In October 1908 Bulgaria proclaimed its independence

Dimitron and the Balkan wars

In October 1908 Bulgaria proclaimed its independence

In 1912, Serbia and Bulgaria joined Greece and Montenegro in a war against the Turks (October 1912–May 1913). The Balkan allies scored a convincing victory but then fell out among themselves over the division of Ottoman possessions in Europe. In the Second Balkan War (June –July 1913), the bulk of the allies, now joined by Romania and Turkey, attacked Bulgaria and, after a series of debilitating defeats, wrested from it portions of newly acquired territories in Macedonia and Thrace, as well as parts of Bulgarian Dobruja. In these two wars Bulgaria lost 58,000 soldiers, an additional 105,000 being wounded.

The tesniaks put up a determined campaign for peace and a

The tesniaks put up a determined campaign for peace and a

At the beginning of the First World War the Bulgarian government carefully weighed the prospects of the warring alliances, in hopes of siding with the winner and thereby regaining the territories lost in the Second Balkan War and, if possible, to increasing them. In September 1915 Tsar Ferdinand finally became convinced that the Central Powers would prevail. Bulgaria mobilized and attacked Serbia within a month. The BRSDP(t.s.) took a consistently antiwar stance throughout the hostilities.

Dimitrov and the other tesniak deputies repeatedly voted against the war

Dimitrov and the other tesniak deputies repeatedly voted against the war

By September 1918, as soldiers started agitating for the cessation of hostilities, the Allies breached the Salonika front and crushed the Bulgarian defenses in Macedonia. In the ensuing stampede the retreating soldiers, calling for peace and a new government, proceeded to Sofia. Ferdinand called upon the Agrarian leader Aleksandur Stamboliski (1879–1923), whom he released from prison, to pacify the approaching mutineers.

Taking on the assignment, Stamboliski nevertheless formed a common cause with

Taking on the assignment, Stamboliski nevertheless formed a common cause with

The Radomir republic ended almost as soon as it started. On 28 September Bulgaria sued for peace, armistice was signed, and Ferdinand was obliged to abdicate, to be succeeded by his son, Boris III (1894–1943). The imprisoned Dimitrov was uninvolved in these decisions. It was later claimed that he had transmitted a written recommendation to the BRSDP CC that favored unwavering involvement in the uprising. Not that the Radomir incident hurt the tesniaks. The party renamed itself the Bulgarian Communist Party (Narrow Socialists), or BKP(t.s.), in May 1919 and then made its peace with the Comintern.

Dimitrov was elected to the Communist CC. The party’s program, for

Dimitrov was elected to the Communist CC. The party’s program, for

The Communists did not accept Stamboliski’s invitation to join a coalition government. Nor did they support the Treaty of Neuilly (27 November 1919), the peace agreement signed by Stamboliski that deprived Bulgaria of considerable territory (Thrace, pivots on the Yugoslav border) and imposed heavy reparations on the country. After the strikes of 1919–1920, the Communists eyed Stamboliski’s government with increased distaste. Stamboliski, who admittedly relied on a club-wielding peasant paramilitary force, the Orange Guard, was called the Balkan Mussolini.

On 9 June 1923, the anti-Stamboliski coalition of right-wing officers moved against the government to overthrow it and then murdered the prime minister. The BKP CC, in an official proclamation, called the putsch “an armed struggle . . . between the urban and rural bourgeoisies.”

Dimitrov, during the strike action of 1919–1920, he went underground with

Dimitrov, during the strike action of 1919–1920, he went underground with

Released in July, he made a second attempt in December 1920, this time by way of Vienna. Obliged to wait for passage to Moscow, he went to Livorno, Italy, to attend the congress of the Italian Socialist Party (15 January 1921), where he observed the Comintern’s splittist strategy against the Socialist leadership.

Dimitrov’s colleague Hristo Kabakchiev (1878–1940), the leading intellectual of the BKP, represented the Comintern at Livorno. His efforts and those of the Italian leftists produced a split and the emergence of the Italian Communist Party (PCI).

In February 1921 Dimitrov finally made it to Moscow, where he

In February 1921 Dimitrov finally made it to Moscow, where he

Having been elected to the Executive Committee of the Profintern, his primary preoccupation continued to be the Bulgarian Communist trade unions, which he helped build to a force of thirty-five thousand by April 1924.

During the Bulgarian coup d’Etat (June 1923) Aleksabdar Stamboliyski’s government and the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union in general were replaced by Aleksandar Tsankov.

Dimitrov and the Komintern

Given Blagoev’s illness and advanced age and Kolarov’s absence in Moscow,

Given Blagoev’s illness and advanced age and Kolarov’s absence in Moscow,

In May 1934 Dimitron declared that he had made a fatal error. “On June 9, 1923”, he stated, “after the Fascist coup d’Etat, a so called, “neutral” policy was adopted which did not intent to take part in the struggle of the Bulgarian fascist reaction against the Stambouliski government whose peasants took the defense. (RGASPI, 495/195/1, f.22).

In his report (23 June 1923) to a plenum of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI), Karl Radek condemned the spinelessness of the BKP that had led to “the greatest defeat ever suffered by a Communist Party.”

After news of the planned insurgency was leaked to the Tsankov

After news of the planned insurgency was leaked to the Tsankov

The authorities relied on the White Russian emigres (Wrangelites) and the Macedonian irregulars. By 28 September Kolarov and Dimitrov ordered a retreat into Yugoslavia, where they led some two thousand Communist insurgents.

The defeat of the September uprising contributed to the growing fractionalism in the BKP but did not unduly harm Communist standing in Bulgaria.

Moreover, the exiled leadership of Kolarov and Dimitrov— the Foreign Committee,

Moreover, the exiled leadership of Kolarov and Dimitrov— the Foreign Committee,

In February 1924 the Comintern endorsed the conduct of Kolarov and Dimitrov, and in May 1924 the underground BKP conference at Vitosha seconded the Comintern’s endorsement.

During this period Dimitrov traveled to Moscow on several occasions. He represented the BKP in the ECCI delegation that escorted Lenin’s coffin from Gorky to Moscow in January 1924.

Back in Vienna at the end of February 1924, he headed the emigre BKP apparatus, directed the work of the Balkan Communist Federation (BCF), the coordinating body of the Comintern Balkan sections that cultivated the various Balkan national-liberation and minority movements, and served as the ECCI emissary to the Communist Party of Austria (KPO).

He represented the BKP and the Balkan Communist Federation at the

He represented the BKP and the Balkan Communist Federation at the

Already in December 1927 and January 1928, at the BKP conference at Berlin, the delegates of the Young Communist League—Georgi Lambrev, Iliya Vasilev, and Petur Iskrov—started attacking the 1923 leadership. By May 1929, following the Sixth Congress of the Comintern (July–September 1928) with its line of “class against class,” the leftist youth leaders started taking over the BKP.

When the Foreign Bureau of the BKP was reconstituted in Moscow,

When the Foreign Bureau of the BKP was reconstituted in Moscow,

Remember: This party of Tesniek became in 1919 the Bulgarian Communist Party.

“The Tesnieks expressed, according Dimitrov, an intransigent policy towards the social-democratic parties and the absolute and complete subordination of private life, personal and individual interests to the interests of the proletariat”.

It was under these circumstances that the ECCI sent Dimitrov to

It was under these circumstances that the ECCI sent Dimitrov to

Dimitrov in Germany

More precisely:

On 27 February 1933, in the midst of a

More precisely:

On 27 February 1933, in the midst of a

Meanwhile, Dimitrov, two other Bulgarian Communists (Blagoi Popov and Vasil Tanev),

Meanwhile, Dimitrov, two other Bulgarian Communists (Blagoi Popov and Vasil Tanev),

Dimitrov’s defense had four important elements.

despite enormous obstacles placed in

Dimitrov’s defense had four important elements.

despite enormous obstacles placed in

Dimitrov boldly defended “Communist ideology, my ideals,” as well as the Communist International and its program of proletarian dictatorship and the “World Union of Soviet Republics.”

He presented himself as a patriotic Bulgarian Communist who resented the racialist Nazi charge that he hailed from a “savage and barbarous” country: “It is true that Bulgarian fascism is savage and barbarous. But the Bulgarian workers and peasants, the Bulgarian people’s intelligentsia are by no means savage and barbarous.”

Finally, he criticized the Social Democratic leaders, Dimitrov exacted from Goebbels

Finally, he criticized the Social Democratic leaders, Dimitrov exacted from Goebbels

The fact that this admission was exacted from Goebbels, that Dimitrov paid compliments to the Anarchists (while disclaiming that van der Lubbe could be a “genuine” Anarchist), that he provoked Goring into making threats once Dimitrov was “out of the courtroom,” still received far greater attention in the West than in the councils of the Comintern. The court sentenced van der Lubbe to death on 23 December 1933, after having simultaneously acquitted Dimitrov, Popov, Tanev, and Torgler for lack of evidence.

Dimitrov’s returned to Moscow on 27 February 1934 as was granted Soviet citizenship by the USSR in order to avoid the death sentence.

In fact, by 1 April Stalin was already encouraging him to

In fact, by 1 April Stalin was already encouraging him to

Remember: The Communist attitude, emerged from the early Communist view that fascism was evidence of capitalism’s decay. The defense of the capitalist order through terror was evidence of the coming revolutionary dawn. This policy was pursued even after Hitler banned the KPD, Communist statements continuing to portray Nazism as a passing phenomenon well into the fall of 1933. And when armed resistance against fascism commenced—in Austria (February 1934), it was the Social Democrats, not the Communists, who took up arms against Chancellor Dollfuss’s fascist dictatorship. In this context, Dimitrov’s militancy in the Leipzig dock represented a significant departure from the simplicity of the above declarations and was a major contribution against fascism .

Germany’s growing strength and aggressiveness—her denunciation of the disarmament clauses in

Germany’s growing strength and aggressiveness—her denunciation of the disarmament clauses in

The Franco-Soviet alliance (May 1935) and the earlier entrance of the USSR into the League of Nations represented an important success of M. Litvinov’s Foreign Commissariat over the revolutionary aspirations of the Comintern.

In this decisive change—which increasingly transformed the Communist International from the headquarters of world revolution to an auxiliary in the struggle against fascism—Dimitrov played a leading role—hence his central function at the Seventh World Congress of the Comintern (July–August 1935).

There is little doubt that the Comintern’s about-face of 1935 represented the most momentous change in the history of Stalinized communism.

Dimitrov stressed that fascism was a “substitution of one state form

Dimitrov stressed that fascism was a “substitution of one state form

Dimitrov proposed new negotiations with the Social Democrats, his aims (and those of the Soviet leadership and the Comintern) were significantly broader. He was proposing an opening to all enemies of fascism, beyond the working class and its parties—including peasants, liberal elements, and the confessional groups.

Nor did he fail to chastise the Communists for their inattention to the motifs of patriotism and national pride, which became successful recruiting themes for the fascist upsurge in many countries.

Dimitrov and the popular front

Dimitrov dominated the congress so thoroughly that his elevation to the

Dimitrov dominated the congress so thoroughly that his elevation to the

Dimitrov’s speech had the effect of cadence breaking on a militant organization whose rank and file clearly craved some way out of their isolation. The Popular Front strategy, with its stress on combat against fascism and its war preparations, necessarily softened the struggle against capitalism and hence diluted the Comintern’s raison d’être of class war and world revolution, hence the Comintern transformed into a coalition controlled by the USSR.

This paradox is explained by the emergency the new definitions of Soviet state interest, not necessarily that of the Comintern member parties that were now obliged to abandon the search for revolutionary opportunities.

Comintern: between internationalism and “nationalism”

Stalin freely expressed a hierarchy of

Comintern: between internationalism and “nationalism”

Stalin freely expressed a hierarchy of

The same approach was expressed about Turkey: “We shall drive the Turks into Asia. What is Turkey? There are two million Georgians there, one and a half million Armenians, a million Kurds, and so forth. The Turks amount to only six or seven million” (25 November 1940).

These aspects, established “ideologically” after the VII Congress of the Comintern, where the outcome of Stalin’s thinking on Russia’s international role. It was marked by a certain “nationalism”. Moreover, the period of the nonaggression pact with Germany, led to a “healthy nationalism”. The question is “nationalism or state interests”?

Under the circumstances, it is not unusual to encounter certain lesser

Under the circumstances, it is not unusual to encounter certain lesser

Hungarian leader Matyas Rakosi hoped that after the war Hungary would retain Transylvania and Carpatho-Ukraine.

Czech Communist Zdenek Nejedly probably was not pleased to learn that his Polish comrades wanted to retain Tetschen.

Nor was it pleasing that the Czechoslovak leadership evidently wanted to expel the Hungarian minority after the war.

These political problems were connected to the organisational problems of the Comintern.

According to one letter sent by Dimitrov to Stalin on 1

According to one letter sent by Dimitrov to Stalin on 1

“III. Regarding the Comintern Leadership

It is essential to change the methods of work and leadership in the Comintern, taking into account that it is impossible effectively to oversee from Moscow every detail of life of all 65 sections of the Comintern, which find themselves in very different conditions (parties in the metropolis and parties in the colonies, parties in highly developed industrial countries and in the predominantly peasant countries, legal and illegal parties, etc).

It is necessary to concentrate on the general political guidance of the Communist movement, on assistance to the parties in basic political and tactical questions, on creating a solid Bolshevik leadership in the local Communist parties, and on strengthening the Communist parties with workers while reducing the heavy bureaucratic apparatus of the ECCI.

It is essential to further promote Bolshevik self-criticism. Fear of this [self-criticism] has at times led to failure to clarify important political problems (questions of the current stage of the crisis and of the so-called military-inflationary juncture, the assessment and lessons of the Austrian events, etc.).

It is impossible to change the methods of leadership and work in the Comintern without partially renewing the cadres of the Comintern workers.

It is especially essential to secure close ties between the Comintern leadership and the Politburo of the VKP(b)”.

The decision of Comintern’s dissolution was taken as early as April

The decision of Comintern’s dissolution was taken as early as April

The Comintern, too, was formed in such a period in Lenin’s time. “Today”, stated Stalin, “the national tasks of the various countries stand in the forefront. But the position of the Com[munist] parties as sections of an international organization, subordinated to the Executive Committee of the CI, is an obstacle” (20 April 1941).

The last period of the Comintern

Dimitrov immediately took Stalin’s idea “of discontinuing the activities of the

Dimitrov immediately took Stalin’s idea “of discontinuing the activities of the

By 12 May 1941 Zhdanov told Dimitrov that the resolution on discontinuing the activities of the Comintern, which was being prepared, “must be grounded in principle,” as hostile interpretations would have to be parried. In any case, “our argumentation should evoke enthusiasm in the Com[munist] parties, rather than create a funereal mood and dismay,” but again, the “matter is not so urgent: there is no need to rush; instead, discuss the matter seriously and prepare.”

The German attack on the Soviet Union appeared to give the

The German attack on the Soviet Union appeared to give the

Dimitrov felt these changes quite directly after the removal of the Comintern staff to Kuibyshev and Ufa in the fall of 1941. He noted that the Comintern and he himself were not in evidence at public occasions. For the first time in many years he was not on the Moscow honor presidium on the anniversary of the revolution. Generally, he accepted that there was “no need to emphasize the Comintern!” (7 November 1941).

The Soviet agencies were taking over parts of the Comintern operations,

The Soviet agencies were taking over parts of the Comintern operations,

The figure of P. M. Fitin, the chief of the Fifth (Intelligence) Directorate of the NKVD (1940–1946), increasingly loomed large in Comintern operations, not only because his network serviced (and controlled) many of the Comintern’s communications. In 1943, when Stalin finally dissolved the Comintern, Fitin went to see Dimitrov “about using our [Comintern] radio communications and their technical base in the future for the needs” of the NKVD (11 June 1943).

Likewise, the Red Army Intelligence Directorate took its cut a day

Likewise, the Red Army Intelligence Directorate took its cut a day

Stalin’s decision to dissolve the Comintern came at the end of the organization’s steady decline. The purges played an important part, Dimitrov himself having offered no resistance to Stalin’s suggestions that he lure the “Trotskyist” Willi Munzenberg back to Moscow or to the arrests of Moskvin, Knorin, and the other leading Comintern officials.

An example of this policy: Let’s see the archives

“STRICTLY SECRET

SUBJECT TO

An example of this policy: Let’s see the archives

“STRICTLY SECRET

SUBJECT TO

Reproduction prohibited TO THE 4TH PART OF THE SPECIAL SECTOR

OF THE VKP(b) CC, MOSCOW, THE KREMLIN

[Handwritten across the top of the text: "I agree with Cde. Dimitrov

[V]/ Molotov 10 December

Cde. Stalin agrees. I sent to Cde. Dimitrov. Molotov"]

CABLE

from KUYBYSHEV sent at 2325 9 December 1941

arrived at the VKP(b) CC for decipherment at 0730 10 December 1941

Incoming Nº 4202/sh

MOSCOW, VKP(b) CC, to Cdes. STALIN, MOLOTOV, BERIA, and MALENKOV.

A group of Iranian Communists, former political prisoners, has begun to

A group of Iranian Communists, former political prisoners, has begun to

At the same time a People's Party with a democratic program has been created in Iran by a democratic figure Suleiman Mirza. Mirza has been fighting for democratic reform in Iran for 30 years now. Some Iranian Communists also participate in this People's Party.

Considering the special conditions of Iran (joint occupation with the British,

Considering the special conditions of Iran (joint occupation with the British,

Therefore I would suppose that in the present situation the Communist Party ought not be revived but that the Communists ought to operate in the People's Party and pursue a policy of:

1. Fighting for the democratization of Iran;

2. Defending the interests of the workers;

3. Strengthening friendly relations between Iran and the Soviet Union;

4. Completely

3. Strengthening friendly relations between Iran and the Soviet Union;

4. Completely

propaganda.

Along with this, the Communist should work to create trade unions and peasant organizations. I also consider it inadvisable for a delegate from the Iranian Communists to be sent to us since this fact will be also used by our enemies in Iran. One of our suitable comrades under suitable legal cover, who could help the Iranian comrades in pursuing this policy, could be sent instead.

If there are to be no other instructions from you I am thinking of sending the Iranian comrades advice to this effect.

DIMITROV

Deciphered at 1220 10 December 1941. Six copies printed. Kozlov,

Nezlobin, Luk'yanova. [Stamp: draft and cipher text destroyed] Illegible signature

In fact, although Dimitrov protected various foreign Communists after 1939—for example,

In fact, although Dimitrov protected various foreign Communists after 1939—for example,

As the Comintern declined and acquired new camouflage, Dimitrov increasingly concentrated on the Balkan questions. Although he did not return to Bulgaria until November 1945, more than a year after the Soviet takeover, he was deeply involved in the affairs of his native land, which he would soon dominate as the de facto party leader and prime minister.

The growing success of Tito’s Partisans in Yugoslavia created new conditions in the Balkan region, favorable to Yugoslav solutions for such thorny issues as that of Macedonia. Precisely because under the Stalinist dispensation nationhood was the decisive element in territorial claims, it was very important to decide whether the Macedonians were a separate nationality or simply a Bulgarian regional group.

Dimitrov’s approach to this issue went through several phases. In Dimitrov’s

Dimitrov’s approach to this issue went through several phases. In Dimitrov’s

Dimitrov and the Balkans

In the spring of 1944 Dimitrov maintained that the Macedonians were

In the spring of 1944 Dimitrov maintained that the Macedonians were

Since Dimitrov envisioned the “ethnic” federation only within the dualist scheme, and since Bulgaria, as a defeated Axis country, really needed Yugoslavia’s international sponsorship, his thinking on Macedonia evolved following 27 October 1944, when he was still entreating.

Tito “to explain to the Maced[onian] comrades that to all intents

Tito “to explain to the Maced[onian] comrades that to all intents

Stalin, however, was opposed to the “ethnic” federation, which he saw as a Yugoslav attempt at “absorption of Bulgaria.” He favored a dualist federation, “something along the lines of the former Austria- Hungary.” In any case, being increasingly suspicious of Tito’s intention he saw Yugoslav policy as excessive: “The Yugoslavs want to take Greek Macedonia”.

They want Albania, too, and even parts of Austria and Hungary.

They want Albania, too, and even parts of Austria and Hungary.

The federative schemes soured thereafter. Dimitrov quickly detected the prevailing mood with Stalin against the “unhealthy sentiments” of the Yugoslavs, who were subject to a “certain degree of ‘dizziness with success’ and an inappropriate, condescending attitude toward Bulgaria and even toward the Bulg[arian] Com[munist] Party” (8 April 1945). And by the fall of 1945 there were irritations with the Yugoslav introduction into Pirin Macedonia of the new Macedonian linguistic standard, which was regarded as “Serbianization”— and in part certainly was.

The Yugoslavs kept pursuing the exchange of Pirin Macedonia for the

The Yugoslavs kept pursuing the exchange of Pirin Macedonia for the

At the meeting, Dimitrov was the whipping boy in Stalin’s outbursts against Tito. On 24 January Stalin sent Dimitrov a sharp letter questioning his statements at a Bucharest press conference, where Dimitrov had spoken about the inevitability of a federation that would unite all East European people’s democracies, including Greece.

The Soviet party organ Pravda publicly disavowed Dimitrov’s remarks on 29

The Soviet party organ Pravda publicly disavowed Dimitrov’s remarks on 29

Under the circumstances, the Yugoslavs were duty-bound to “restrict” the Greek partisan movement. “We are not bound by any ‘categorical imperatives.”

Stalin argued: “The key issue is the balance of forces” (10 February 1948).

And Dimitrov replied:

- Dimitrov certainly.

Dimitrov certainly smarted from Stalin’s lashes of February 1948. This was

Dimitrov certainly smarted from Stalin’s lashes of February 1948. This was

His most obvious human failing was a curiously discreet sort of

His most obvious human failing was a curiously discreet sort of

Dimitrov was a deeply emotional man. He gloried in natural beauty, as during his treatments in southern Crimea in 1938. His personal life was complicated and full of tragedies. His first wife, Ljubica Ivosevic Dimitrova, who suffered from incurable mental disease, committed suicide in Moscow on 27 May 1933, while he was in the Moabit prison in Berlin. After he visited her resting place at the Moscow crematorium on 28 May 1934, he wrote, in a cri de coeur, that he felt “so lonely, so terribly personally unhappy”.

Conclusion

Back in Moscow in 1934, he seems to have broken up

Back in Moscow in 1934, he seems to have broken up

Illness accompanied Dimitrov in his last decades. He suffered from diabetes, chronic gastritis, a diseased gall bladder, and a variety of other ailments. Although he had to go to hospitals and health spas at some very trying periods of Soviet history, these were no mere political illnesses—“No luck!” he wrote after another painful bout of illness on 11 October 1943—but his chief malady was the inability to offer resistance to Stalin.

Georgi Dimitrov died in Moscow on 2 July 1949. He was

Georgi Dimitrov died in Moscow on 2 July 1949. He was

Archives: Documents

Archives: Documents

![Tito “to explain to the Maced[onian] comrades that to all intents](/_ipx/f_webp&q_80&fit_contain&s_1440x1080/imagesDir/jpg/478057/slide-46.jpg)

1811 - 1817

1811 - 1817 Летописец войны - презентация к 105-летию со дня рождения русского советского поэта, прозаика К.М. Симонова (1915-1979)

Летописец войны - презентация к 105-летию со дня рождения русского советского поэта, прозаика К.М. Симонова (1915-1979) «СВИДАНИЕ С МАСТЕРОМ» Литературная игра по роману М. А. Булгакова "Мастер и Маргарита“ Учитель: Шишкина Алена Викторовна

«СВИДАНИЕ С МАСТЕРОМ» Литературная игра по роману М. А. Булгакова "Мастер и Маргарита“ Учитель: Шишкина Алена Викторовна Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Чувашева С.В.,учитель русского языка и литературы филиала МОУСОШ п.Октябрьский в д.Городище

Чувашева С.В.,учитель русского языка и литературы филиала МОУСОШ п.Октябрьский в д.Городище Свиридов Георгий Васильевич - музыкально общественный деятель

Свиридов Георгий Васильевич - музыкально общественный деятель Нил Гейман – популярный английский автор современной прозы. Роман «Американские боги» (2001 г.) ввёл его в число наиболее маститых ав

Нил Гейман – популярный английский автор современной прозы. Роман «Американские боги» (2001 г.) ввёл его в число наиболее маститых ав Пространственная организация рассказа И. Бунина Чистый понедельник

Пространственная организация рассказа И. Бунина Чистый понедельник ПО ПРОИЗВЕДЕНИЮ С.Т. АКСАКОВА «БУРАН»

ПО ПРОИЗВЕДЕНИЮ С.Т. АКСАКОВА «БУРАН» Анна Андреевна Ахматова Выполнила: Овчинникова. В. 9-в Проверила:

Анна Андреевна Ахматова Выполнила: Овчинникова. В. 9-в Проверила: Презентация на тему "А.Н. Островский – создатель русского театра" - скачать презентации по Литературе

Презентация на тему "А.Н. Островский – создатель русского театра" - скачать презентации по Литературе Цель: познакомить учащихся с основными этапами жизни писателя, сформировавшими его личность и отразившимися в творчестве.

Цель: познакомить учащихся с основными этапами жизни писателя, сформировавшими его личность и отразившимися в творчестве.  История создания и замысел повести Н.В.Гоголя “Шинель”. Выполнили работу: Самородов. А.А, Розин. М.А, Сиротинин.С.А.

История создания и замысел повести Н.В.Гоголя “Шинель”. Выполнили работу: Самородов. А.А, Розин. М.А, Сиротинин.С.А. Презентация на тему "Были дебри да леса, стали в дебрях чудеса" - скачать презентации по Литературе

Презентация на тему "Были дебри да леса, стали в дебрях чудеса" - скачать презентации по Литературе Шестидесятые годы ХХ века, оттепель. Отечественная музыка второй половины ХХ века. Родион Щедрин

Шестидесятые годы ХХ века, оттепель. Отечественная музыка второй половины ХХ века. Родион Щедрин Презентация на тему "Анализ текста О.Н.Безымянной «Орел и Воробьи»" - скачать презентации по Литературе

Презентация на тему "Анализ текста О.Н.Безымянной «Орел и Воробьи»" - скачать презентации по Литературе Презентация на тему Народный фольклор: потешки, считалки, колыбельные песенки, загадки…

Презентация на тему Народный фольклор: потешки, считалки, колыбельные песенки, загадки… Великая Отечественная война в истории моей семьи. Зайнуллина Ильвина

Великая Отечественная война в истории моей семьи. Зайнуллина Ильвина Джоэль Харрис. Проделки братца кролика

Джоэль Харрис. Проделки братца кролика Викторина на классный час

Викторина на классный час Сильнее смерти. К дню памяти Анны Франк

Сильнее смерти. К дню памяти Анны Франк День лермонтовской поэзии в библиотеке

День лермонтовской поэзии в библиотеке Агния Львовна Барто

Агния Львовна Барто Саманта Смит

Саманта Смит Макс Альперт

Макс Альперт А.П.ЧЕХОВ Творческая биография (1860 - 1904) .

А.П.ЧЕХОВ Творческая биография (1860 - 1904) . Бородино, М.Ю. Лермонтов (5 класс)

Бородино, М.Ю. Лермонтов (5 класс) Викторина Смех и горе у Бела моря

Викторина Смех и горе у Бела моря