Содержание

- 2. Vocabulary Intermittent adj \ ˌintərˈmitᵊnt \ — occurring at irregular intervals; not continuous or steady; прерывистый

- 3. Date:1337 - 1453 Hundred Years’ War, intermittent struggle between England and France in the 14th–15th century

- 4. In the first half of the 14th century, France was the richest, largest, and most populous

- 5. Origins of the Hundred Years War When Edward III of England came to blows with David

- 6. Edward III, the Black Prince and English Victories Edward III pursued a twofold attack on France.

- 7. French Ascendance and a Pause Tensions rose again as England and France patronized opposing sides in

- 8. By 1380, the year both Charles V and du Guesclin died, both sides were growing tired

- 9. French Division and Henry V In the early decades of the fifteenth-century tensions rose again, but

- 10. The Treaty of Troyes and an English King of France The struggles between the houses of

- 11. The Treaty was accepted in English and Burgundian held lands—largely the north of France—but not in

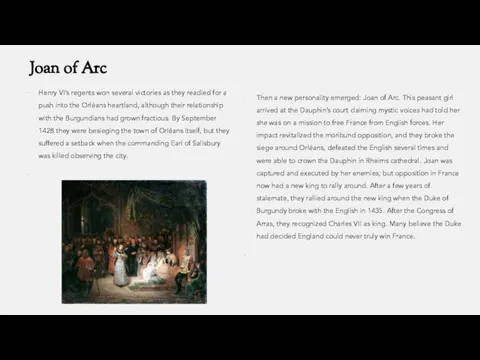

- 12. Joan of Arc Henry VI’s regents won several victories as they readied for a push into

- 13. French and Valois Victory The unification of Orléans and Burgundy under the Valois crown made an

- 14. Significance of the Hundred Years’ War The Hundred Years’ War, begun on the pretext of an

- 15. The initial claim to the French throne can be explained only by Edward III’s strong ties

- 16. The 14th and 15th centuries marked, both in France and in England, a prolonged struggle for

- 18. Скачать презентацию

Vocabulary

Intermittent adj \ ˌintərˈmitᵊnt \ — occurring at irregular intervals; not continuous or steady; прерывистый

legitimate adj \ liˈjitəmət \

Vocabulary

Intermittent adj \ ˌintərˈmitᵊnt \ — occurring at irregular intervals; not continuous or steady; прерывистый legitimate adj \ liˈjitəmət \

Date:1337 - 1453

Hundred Years’ War, intermittent struggle between England and France

Date:1337 - 1453

Hundred Years’ War, intermittent struggle between England and France

Participants: France, England

Location: Europe, Flanders, France, Spain, Kingdom of Navarre

In the first half of the 14th century, France was the

In the first half of the 14th century, France was the

Origins of the Hundred Years War

When Edward III of England came

Origins of the Hundred Years War

When Edward III of England came

Edward III, the Black Prince and English Victories

Edward III pursued a

Edward III, the Black Prince and English Victories

Edward III pursued a

With France leaderless, with large parts in rebellion and the rest plagued by mercenary armies, Edward attempted to seize Paris and Rheims, perhaps for a royal coronation. He took neither but brought the "Dauphin"—the name for the French heir to the throne - to the negotiating table. The Treaty of Brétigny was signed in 1360 after further invasions: in return for dropping his claim on the throne. Edward won a large and independent Aquitaine, other land and a substantial sum of money. But complications in the text of this agreement allowed both sides to renew their claims later on.

French Ascendance and a Pause

Tensions rose again as England and France

French Ascendance and a Pause

Tensions rose again as England and France

By 1380, the year both Charles V and du Guesclin died,

By 1380, the year both Charles V and du Guesclin died,

French Division and Henry V

In the early decades of the fifteenth-century

French Division and Henry V

In the early decades of the fifteenth-century

After a misstep where a treaty was signed between the rebels and England, only for peace to break out in France when the English attacked, in 1415 a new English king seized the opportunity to intervene. This was Henry V, and his first campaign culminated in the most famous battle in English history: Agincourt. Critics might attack Henry for poor decisions which forced him to fight a larger pursing French force, but he won the battle. While this had little immediate effect on his plans for conquering France, the massive boost to his reputation allowed Henry to raise further funds for the war and made him a legend in British history. Henry returned again to France, this time aiming to take and hold land instead of carrying out chevauchées; he soon had Normandy back under control.

The Treaty of Troyes and an English King of France

The struggles

The Treaty of Troyes and an English King of France

The struggles

The Treaty was accepted in English and Burgundian held lands—largely the

The Treaty was accepted in English and Burgundian held lands—largely the

Joan of Arc

Henry VI’s regents won several victories as they readied

Joan of Arc

Henry VI’s regents won several victories as they readied

Then a new personality emerged: Joan of Arc. This peasant girl arrived at the Dauphin’s court claiming mystic voices had told her she was on a mission to free France from English forces. Her impact revitalized the moribund opposition, and they broke the siege around Orléans, defeated the English several times and were able to crown the Dauphin in Rheims cathedral. Joan was captured and executed by her enemies, but opposition in France now had a new king to rally around. After a few years of stalemate, they rallied around the new king when the Duke of Burgundy broke with the English in 1435. After the Congress of Arras, they recognized Charles VII as king. Many believe the Duke had decided England could never truly win France.

French and Valois Victory

The unification of Orléans and Burgundy under the

French and Valois Victory

The unification of Orléans and Burgundy under the

War soon began again when the English broke the truce. Charles VII had used the peace to reform the French army, and this new model made great advances against English lands on the continent and won the Battle of Formigny in 1450. By the end of 1453, after all, English land bar Calais had been retaken and feared English commander John Talbot had been killed at the Battle of Castillon, the war was effectively over.

Significance of the Hundred Years’ War

The Hundred Years’ War, begun on

Significance of the Hundred Years’ War

The Hundred Years’ War, begun on

The initial claim to the French throne can be explained only

The initial claim to the French throne can be explained only

The 14th and 15th centuries marked, both in France and in

The 14th and 15th centuries marked, both in France and in

Первые попытки реформ и XX съезд КПСС

Первые попытки реформ и XX съезд КПСС Периодизация всемирной истории. Первобытная эпоха.

Периодизация всемирной истории. Первобытная эпоха. 20140108_drevniy_gorod_tanais

20140108_drevniy_gorod_tanais История балов в России / Танцевальная культура России в XIX веке _

История балов в России / Танцевальная культура России в XIX веке _ Театр «Березіль»

Театр «Березіль»  Советское общество в первые послевоенные десятилетия (1945-1964 гг.)

Советское общество в первые послевоенные десятилетия (1945-1964 гг.) ФРАНКО – ПРУССКАЯ ВОЙНА Объединение Германии.

ФРАНКО – ПРУССКАЯ ВОЙНА Объединение Германии.  Они служили в Афганистане

Они служили в Афганистане К 9 мая. Родина у нас одна

К 9 мая. Родина у нас одна Решите тест

Решите тест  Памятники советским воинам в Европе

Памятники советским воинам в Европе Политический кризис 1993 года

Политический кризис 1993 года Мы объединены желанием рассказать стране о своих предках

Мы объединены желанием рассказать стране о своих предках Наши прадеды - Шакиров Габдрафик Шакирович, Фазылов Мингаж Нажмутдинович

Наши прадеды - Шакиров Габдрафик Шакирович, Фазылов Мингаж Нажмутдинович Иван Грозный Презентация студента МЭСИ А.Карапетяна

Иван Грозный Презентация студента МЭСИ А.Карапетяна <<9мая – День победы >> Гвазава Кристина 7Б класс, школа 345 ,2010 год

<<9мая – День победы >> Гвазава Кристина 7Б класс, школа 345 ,2010 год Презентация на тему "Итоговый тест" - презентации по Истории скачать бесплатно

Презентация на тему "Итоговый тест" - презентации по Истории скачать бесплатно Neatkarīgas Latvijas valsts veidošanās

Neatkarīgas Latvijas valsts veidošanās Формирование средневековых городов

Формирование средневековых городов История создания Вооружённых Сил Российской Федерации

История создания Вооружённых Сил Российской Федерации Районная научно – практическая конференция исследовательских работ учащихся ТЕМА: « Дети во время Великой Отечественной войны»

Районная научно – практическая конференция исследовательских работ учащихся ТЕМА: « Дети во время Великой Отечественной войны» Историко-архитектурные памятники усадьбы Царицыно

Историко-архитектурные памятники усадьбы Царицыно Федеративный договор. Антитеррористическая кампания в Чечне

Федеративный договор. Антитеррористическая кампания в Чечне Россия в 1991 – 2020 гг

Россия в 1991 – 2020 гг Битва за Москву. 30 сентября 1941 - 20 апреля 1942 «Велика Россия, а отступать некуда- позади Москва!»

Битва за Москву. 30 сентября 1941 - 20 апреля 1942 «Велика Россия, а отступать некуда- позади Москва!» Мир без интернета

Мир без интернета Внутренняя и внешняя политика преемников Петра I

Внутренняя и внешняя политика преемников Петра I Презентация на тему "Подготовка крестьянской реформы" - презентации по Истории скачать

Презентация на тему "Подготовка крестьянской реформы" - презентации по Истории скачать