Содержание

- 2. The Comintern: Institutions and people Dr Nikolaos Papadatos, University of Geneva Global Studies Institute Email: nikolaos.papadatos@unige.ch

- 3. INDEX 1 The formation of the Communist party of Yougoslavia (CPY) 2 Tito and Gorkic 3

- 4. The formation of the Communist party of Yougoslavia (CPY) The Bolshevik Revolution of November, 1917, found

- 5. In the elections for the Constituent Assembly on November 28, 1920, the CPY scored a notable

- 6. Sima Markovič, a teacher from Belgrade— the leading Serbian Communist—was known even by Stalin as “Comrade

- 7. Markovič finally capitulated at the Fourth Congress of the CPY held at Dresden, Germany, in November,

- 8. Tito and Gorkic The remaining leadership of the CPY fled the country and for years operated

- 9. It accepted, at Stalin’s orders, the Popular Front policy of collaborating with non-Communist and anti-Fascist parties.

- 10. At the end of 1937, Tito was given in Moscow the position of the General Secretary,

- 11. In the 1920s and 1930s the CPY was a byword for factional intrigue. Behind those clashes,

- 12. The May election was for many a moral victory for the opposition, despite the government's comfortable

- 13. The Comintern's decision to quash these resolutions of April 1936, and summon the leadership to Moscow

- 14. An agreement of some sort had to be achieved, whether officially or unofficially and no matter

- 15. At his first meeting with the Central Committee on returning from Moscow he called on all

- 16. Gorkic stuck to his guns and took a detailed statement on party reorganization when summoned to

- 17. Understandably, this enquiry gave new heart to those who had opposed Gorkic in 1935 and 1936

- 21. Labud Kusovac, the party’s representative on the committee for aid to republican Spain, stated that the

- 22. Apparently as a result of this visit the French Communist Party supported Maric in his job

- 23. The end of Gorkić’s era gave new possibilities to his opposition and Tito, as Gorkić’s man,

- 24. On his personal initiative this informal group constituted itself as the temporary leadership of the CPY,

- 25. When he left Moscow, he was once again supplied with imperative orders. He was supposed to

- 26. Once again Tito had to go through the same process of verification in Moscow. He wrote

- 27. This was the strategy known as “The Popular Front created from below”, that is to say

- 28. The CPY was told that it should in the first place explain to its members and

- 29. d. Finally, the conclusion was that the general crisis of capitalism would certainly became even more

- 30. These instructions, on each of the three occasions, were created during a process of consultation among

- 31. He gladly explained to Bozidar Adžija the concept of “Popular front from above”, that is to

- 32. For Tito, the succession of defeats of Norway, Holland and Belgium was a clear confirmation of

- 33. The radicalization of his strategy reached its peak after the defeat of France, when he declared

- 34. Moscow did not approve of this radical strategy of the CPY. On September 28th Tito was

- 35. The Conference was opened by Tito’s extensive report in his capacity of the acting head of

- 36. In October he arrived in Moscow, he was able to make an oral presentation on the

- 37. The Executive Committee addressed the issue of creating a people’s government: “In the present situation, the

- 38. Yet, the Party should not put forward the slogan on the defence of the frontiers of

- 39. After the defeat of France, and Hitler’s victory in Western Europe, the Nazi peril became real

- 40. In the meantime, the communication was ensured via radio operated by Tito’s friend Josip Kopinič, a

- 41. The only way to effectively defend its independence and keep the country out of the imperialist

- 42. In Croatia and in Bosnia-Herzegovina the Nazi’s established a puppet genocidal regime under the guidance of

- 43. “The struggle against reactionary governments which refused to grant the people their democratic rights and liberties

- 44. He made no reference to this possibility in his telegrams to Moscow. Kopinič transmitted only his

- 45. During this stage of combat the CPY should fight for the liberation from foreign occupation and

- 46. Tito’s actions from the moment he became the acting head of CPY in 1937 until June

- 47. Hitler’s attack and a series of defeats of the Red Army forced the Soviet government and

- 48. When eventually they entered small provincial towns in Serbia, the local partisan commanders started destroying all

- 49. The tasks of people’s councils were to provide food and material aid to partisans units, to

- 50. The theory of two phases called for an urgent alliance with all resistance groups and in

- 51. Mihailović could rely on the prestige of his rank and could benefit from the network of

- 52. Only by fighting the Germans, but primarily the entire local administration that was incorporated in the

- 53. Tito in fact mentioned Mihailović’s units only after he had met Colonel Mihailović and reached an

- 54. Dimitrov’s demand for clarification arrived in December 1941 at the time when the German offensive in

- 55. Tito failed to inform Moscow of his new strategy but the Yugoslav government in exile notified

- 56. Tito, however, continued his own agenda of denouncing Mihailović to Moscow and fighting his units in

- 57. Dimitrov’s response underlined the existing disagreements. He agreed with the creation of NKOJ, but he didn’t

- 58. Dimitrov’s evocation of the “present phase” was an explicit reference to the theory of “two phases”,

- 59. The fate of Yugoslavia was sealed when Stalin and Roosevelt agreed that there would be no

- 60. The second session of the AVNO J, held in the town of Jajce on the night

- 61. Churchill wrote a personal letter to Tito in January 1944. In his letter the British Prime

- 62. The only solution possible was, as Anthony Eden, British Minister of Foreign Affairs explained to Tito

- 63. Therefore, in the beginning of 1944 in direct contacts with Western Allies Tito imposed his solution

- 64. The Tehran decisions thus were realized and the decisive Partisan victory in Serbia in the fall

- 65. Tito’s Yugoslavia almost singlehandedly defied the West on the issue of Trieste and Venezia-Guilia. The USSR

- 66. The Yugoslav-Soviet crisis was presented as a political top-level conflict within the Cominform. In fact, the

- 67. “This controversy was a matter of great importance for the internal development of our country because

- 68. The Yugoslav-Soviet conflict was not provoked by ideological differences. It was purely a matter of state

- 69. The German attack on Yugoslavia did not incite Tito to act, but Hitler’s attack on the

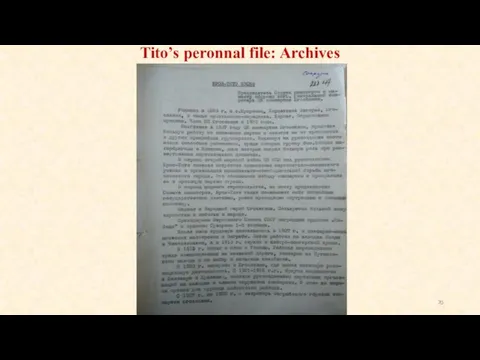

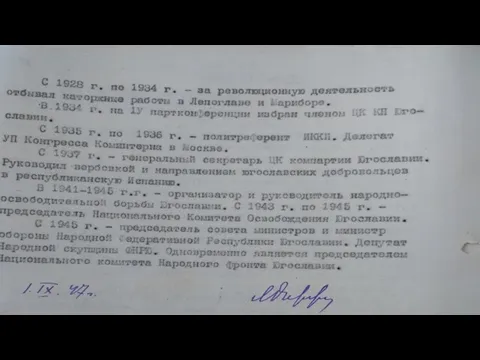

- 70. Tito’s peronnal file: Archives

- 80. Скачать презентацию

The Comintern: Institutions and people

Dr Nikolaos Papadatos, University of Geneva

Global Studies

The Comintern: Institutions and people

Dr Nikolaos Papadatos, University of Geneva

Global Studies

Email: nikolaos.papadatos@unige.ch

INDEX

1 The formation of the Communist party of Yougoslavia (CPY)

2

INDEX

1 The formation of the Communist party of Yougoslavia (CPY)

2

3 Tito and the Comintern

4 Tito Kusovac and Maric

5 Tito and his leadership within the CPY

6 Tito as Secretary-General

7 Tito and his partisans

8 Titos’s road to power

9 Conclusion: The Stalin-Tito split

10 Tito’s peronnal file: Archives

The formation of the Communist party of Yougoslavia (CPY)

The Bolshevik Revolution

The formation of the Communist party of Yougoslavia (CPY)

The Bolshevik Revolution

The national and religious animosities contributed to the temporary rise of Communism. The Socialist Workers’ Party of Yugoslavia (Communists) was founded in Belgrade in late April, 1919. Its initiators were from all provinces. The Second Party Congress was held in Vukovar, Croatia, during June 20-24, 1920. The Party now accepted the “ Conditions of Admission” to the Comintern and joined it. Its membership was about 65,000, and its new name the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. A revolutionary program along the Leninist lines was adopted, following the directives of the Soviet-sponsored Balkan Communist Federation.

In the elections for the Constituent Assembly on November 28, 1920,

In the elections for the Constituent Assembly on November 28, 1920,

A month later the Government outlawed the CPY. Responding to the subsequent Communist terrorism by a special Law for the Defense of the State, the Government in Belgrade inaugurated a real reign of terror against the Communist movement. Worse than persecutions that seriously depleted the ranks of the CPY was the internal strife within the Party.

Sima Markovič, a teacher from Belgrade— the leading Serbian Communist—was known

Sima Markovič, a teacher from Belgrade— the leading Serbian Communist—was known

Comintern itself intervened. The refusal of Markovič to discard his views almost completely destroyed the CPY. By January, 1924, the CPY had only about a thousand members. The Fifth Congress of the Comintern (June 17 -July 8, 1924) rebuked Markovič and its resolution explicitly stated that Croatia, Slovenia and “Macedonia” had the right to secede from Yugoslavia. Stalin himself, who was the foremost Soviet authority on the national question, delivered a speech during a session of the Yugoslav Commission of the Comintern on March 30, 1925. He confirmed the right of nations in Yugoslavia to “self-determination, including the right to secession.”

Markovič finally capitulated at the Fourth Congress of the CPY held

Markovič finally capitulated at the Fourth Congress of the CPY held

Following the assassination of the Croatian deputies and the death of Stjepan Radić, the President of the Croatian Peasant Party, in the summer of 1928, King Alexander introduced a dictatorship in January, 1929. A wave of persecutions of all opponents of the regime set in. Among numerous Communists who were sent to prison was also Josip Broz, a prominent leader in the Communist-led labor unions and a well-known member of the local Party organization in Zagreb.

Tito and Gorkic

The remaining leadership of the CPY fled the country

Tito and Gorkic

The remaining leadership of the CPY fled the country

Following the assassination of King Alexander in October, 1934, in Marseilles, France, and the downfall of the dictatorship, the Communists started to emerge as a new active political force. In December, 1934, Josip Broz became the member of the Central Committee of the CPY. After fourteen years at home, Broz went to Moscow in early 1935. Here he worked in the Balkan Secretariat of the Comintern under Georgi Dimitrov, the famous Bulgarian Communist. While Broz was in Moscow, the Seventh Congress of the Comintern took place from July 25 to August 21, 1935.

It accepted, at Stalin’s orders, the Popular Front policy of collaborating

It accepted, at Stalin’s orders, the Popular Front policy of collaborating

Absolutely loyal to Stalin and Comintern, Tito, as he was by now known among the Communists, gradually emerged as the new leader of Yugoslav Communism. During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) Tito spent a great deal of time in Paris where the Central Committee of the CPY was then located. He and Gorkič were dispatching hundreds of Yugoslav Communists to the International Brigade in Spain. In the summer of 1937, Gorkič was called to Moscow, removed as the General Secretary, and subsequently liquidated.

At the end of 1937, Tito was given in Moscow the

At the end of 1937, Tito was given in Moscow the

Tito was a determined revolutionary and succeeded in building a unified, fighting revolutionary organization. Although confused by the Nazi-Soviet Agreement of late August, 1939, the Communists were the only political organization in Yugoslavia well prepared for the events after the outbreak of World War II. At the time of the Fifth Land Conference of the CPY that met in Zagreb in October, 1940, the movement could boast of approximately 12,000 disciplined party members and some 30,000 Communists youth.

In the 1920s and 1930s the CPY was a byword for

In the 1920s and 1930s the CPY was a byword for

Liquidationism was the ideology espoused by Milan Gorkic, who preceded Tito as party leader. Under his leadership, in the shadow of developments in France, the party sought a popular front style agreement with the socialist party. Of course, at first sight there were few similarities between the situation in France, where both the communist and socialist parties were legal, and Yugoslavia, where both were illegal. However, the Comintern line required all parties to follow broadly the same policy, and ever since the assassination of King Alexander on 9 October 1934 there had been signs that the dictatorial regime established in 1929 was beginning to weaken. The censorship was relaxed, prominent political prisoners were released, and in February 1935 elections were promised for the following May.

Tito and the Comintern

The May election was for many a moral victory for the

The May election was for many a moral victory for the

When prospects for an alliance improved in the autumn, after the socialists had adopted a new radical program, Gorkic was sent to Yugoslavia in October 1935 to try to finalize these negotiations: again he had no success. Mass arrests during the winter of 1935-1936 showed the clear limits to Stojadinovic's liberalism and revived opposition to Gorkic's tactics. He was forced to summon a meeting of the CPY Central Committee in April 1936, without the prior agreement of the Comintern, and agree to the adoption of a series of resolutions critical of all the attempts at negotiating an alliance with the socialists.

The Comintern's decision to quash these resolutions of April 1936, and

The Comintern's decision to quash these resolutions of April 1936, and

Again negotiations began with the socialists, and again Gorkic stressed the single opposition tactic. Discussions started in Zagreb in autumn 1936 about an agreement for the December 1936 local elections. A joint platform was drafted and sent to the Central Committee for comments and the party's November report to the Comintern was upbeat and optimistic, as was a Gorkic letter to Tito. Once again Gorkic was convinced of the need for agreement at any cost.

An agreement of some sort had to be achieved, whether officially

An agreement of some sort had to be achieved, whether officially

That Gorkic was a Liquidationist there can be no doubt. Not only did he call for a united opposition, but he wanted to facilitate this by legalizing the communist party and thus overcoming the socialists' fear of association with an illegal organization. To this end, he drew up lengthy proposals aimed at completely transforming the party's organizational structure.

At his first meeting with the Central Committee on returning from

At his first meeting with the Central Committee on returning from

The starting point for Gorkic's analysis of the failings of the party were the constant arrests. He therefore proposed legalizing as many party leaders as possible by involving them in the legal and semi-legal trade union work so essential for working class unity. This would inevitably mean the demise of "deep underground commanding committees", which showed little activity and were increasingly irrelevant. "We must be brave enough to recognize this", he wrote in January 1937, "and draw the logical conclusions, which are not", he insisted, "Liquidationist". The old technical apparatus should be abolished, the party rebuilt from below, and the party leadership legalized in Yugoslavia.

Gorkic stuck to his guns and took a detailed statement on

Gorkic stuck to his guns and took a detailed statement on

Gorkic never returned from that visit to Moscow, one of the many victims of Stalin's purges, and at a meeting on 17 August 1937 Tito took over as interim party secretary. His position as interim party leader was automatically endorsed by Moscow. Gorkic had been arrested by the NKVD, not for the ideological sin of Liquidationism, but as a British spy. As a result, the Comintern began a lengthy investigation into the CPY to establish whether Gorkicites existed among the remaining leadership.

Understandably, this enquiry gave new heart to those who had opposed

Understandably, this enquiry gave new heart to those who had opposed

From the start of Tito's period as de facto party leader he began to explore the nature of his dependency on Moscow: a sort of sparring began through which he sought to establish the limitations on independent action. He was determined to act, rather than simply await instructions. To justify such initiatives he was concerned to keep the Comintern informed in detail of what was happening; however, much of what he told the Comintern was highly selective, often glossing over controversial issues.

Labud Kusovac, the party’s representative on the committee for aid to

Labud Kusovac, the party’s representative on the committee for aid to

Kusovac, a former member of the Profintern apparatus and the man responsible for handling Yugoslav volunteers bound for the Spanish civil war, where opposition to Gorkic was widespread, had good contacts with the Comintern and the NKVD. He was visited in Paris by the Comintern emissary Golubovic early in 1938 although no contact was made with Tito who was in the French capital at the same time.

Tito Kusovac and Maric

Apparently as a result of this visit the French Communist Party

Apparently as a result of this visit the French Communist Party

In this dispute, Tito was appealing always for the Comintern to conclude its enquiry rapidly and prevent the party disintegrating. However, far from waiting patiently for a decision, Tito took a series of initiatives to reinforce his position and by-pass the restrictions coming from Moscow. The Comintern enquiry meant that all financial support from Moscow ended and the party journal Proleter had to cease publication. Tito looked to other means of support and first sought to divert money being used to send volunteers to Spain for the more mundane task of keeping the party press operating. Frustrated in this by the opposition of Kusovac, whom he tried to sack as Spanish agent in March 1938, Tito had to appeal for funds to Yugoslavs living abroad.

The end of Gorkić’s era gave new possibilities to his opposition

The end of Gorkić’s era gave new possibilities to his opposition

Tito and his leadership within the CPY

On his personal initiative this informal group constituted itself as the

On his personal initiative this informal group constituted itself as the

Upon his arrival, he first had to justify his actions, and those of the CPY. In the meantime, a whole generation of previous leaders of the CPY had perished in Stalinist purges. Gorkić and his adversaries were eliminated in the same way. They perished in a process of security-inspired folly, supposed to rid the Soviet Union of all unwelcome foreigners, and everything that presented any kind of risk to the survival of the homeland of communism. During his stay in Moscow, from August 1938 to January 1939, Tito managed to obtain approval for his new leadership, and more importantly, for his actions in Gorkić’s era and afterwards.

When he left Moscow, he was once again supplied with imperative

When he left Moscow, he was once again supplied with imperative

Once again Tito had to go through the same process of

Once again Tito had to go through the same process of

This was the strategy known as “The Popular Front created from

This was the strategy known as “The Popular Front created from

The new strategy was presented to the CPY in the Instruction of the Executive Committee of Comintern, dated 29 October 1939, which Tito took with him when he left Moscow on 26 November 1939. The Instruction was partly based on the information he brought from Yugoslavia. He was present at the sitting of the Committee. The Instruction was in fact a precise agenda for the CPY that gave answers to very important issues, such as how to address the situation created by the outbreak of the War.

The CPY was told that it should in the first place

The CPY was told that it should in the first place

Furthermore, the USSR was the only power that followed a peaceful policy of aiding the nations that were fighting for their independence.

England and France were spreading false propaganda by saying that they were fighting for peace and freedom of nations, or they were trying the spread the War by dragging other countries into it.

Therefore, the CPY must oppose any attempt of the ruling bourgeoisie to draw Yugoslavia in the War. Instead, the CPY must fight for the conclusion of a treaty on friendship and mutual aid with the USSR, which is the best guarantee of the freedom and independence of Yugoslav nations.

d. Finally, the conclusion was that the general crisis of capitalism

d. Finally, the conclusion was that the general crisis of capitalism

These were the final instructions that Tito brought with him when he left Moscow for the third and last time in November 1939. On three occasions, during his stays in Moscow, Tito received written instructions which represented the essence of his domestic and foreign policy. The main points were:

The Yugoslav federation, the Popular Front as the essence of the political strategy from either above or below,

the Treaty on friendship with the USSR, keeping Yugoslavia out of the War, and last but not the least,

the prospect of the downfall of capitalism during the imperialist War.

These instructions, on each of the three occasions, were created during

These instructions, on each of the three occasions, were created during

For a party leader with a limited educational background such as Tito, these rather simple concepts, contained in the series of instructions he got in Moscow, represented the sum total of his political ideas. He learned his Moscow lessons well and was never troubled by any kind of intellectual doubt. His political skill and acumen consisted of finding ways to put in practice the strategy that Moscow decided upon in any given moment.

He gladly explained to Bozidar Adžija the concept of “Popular front

He gladly explained to Bozidar Adžija the concept of “Popular front

For Tito, the succession of defeats of Norway, Holland and Belgium

For Tito, the succession of defeats of Norway, Holland and Belgium

In the same time he started purging the Party from all who were still in favour of a “Popular front from above”, that is to say for collaborating with other left-wing parties. The title of Tito’s article announced his strategy and his intentions: For the purity and the bolshevisation of the Party”. As for his attitude towards the Social Democrats, the titles of his articles speak for themselves: Against the revolutionary leaders of the Social Democrats as warmongers and leaders of the anti-Soviet campaign, written in June 1940; and The Unity of Bosses, Police, and Social democrat traitors in the struggle against the workers, written in July 1940.

The radicalization of his strategy reached its peak after the defeat

The radicalization of his strategy reached its peak after the defeat

“The united working class in alliance with the peasantry and with the rest of the working population of Yugoslavia should prepare itself, under the guidance of the CPY, to carry out a struggle against the merciless exploitation of the workers by the capitalists and to lead a decisive battle to preserve the independence of Yugoslavia. The necessary condition for achieving these goals is to overthrow the existing regime and to create a real people’s government; a government of workers and peasants which will rule in the interest of working class, give the people their rights, and ensure the independence of the country by cooperation with the USSR, the country of workers and peasants, a state of gigantic progress and wellbeing, the protector of small nations and the most consistent partisan of peace”. (Tito, Sabrana djela, vol. V, 119-120, “Radnom Narodu Jugoslavije”, Proleter, 3-4, 1940).

Moscow did not approve of this radical strategy of the CPY.

Moscow did not approve of this radical strategy of the CPY.

The culmination of Tito’s radical rhetoric was reached during his introductory speech on the 5th Conference of the CPY, which was secretly organized in October 1940 in Zagreb. He was still just the acting head of him as such, since only the Congress of the CPY could appoint a new Secretary-General. Therefore he wanted to organize a Party congress in Zagreb in the fall of 1940. Moscow did not approve of organizing the Congress because there was a risk that the confidentiality of the Congress could be breached and the Party leadership might end up in Yugoslav prisons. Thus Tito was forced to rename the meeting of 108 delegates from all regional organizations of the CPY as the 5th Conference of the CPY.

The Conference was opened by Tito’s extensive report in his capacity

The Conference was opened by Tito’s extensive report in his capacity

“All activity and efforts of the Party should have an exclusively class basis. We have to put an end to all projects and agreements with the leaderships of various bourgeois, so-called “democratic” parties, which have become more reactionary, genuine agencies of the secret services of French and British instigators of the War. Our Party and all sections of the Comintern must undertake the following tasks: the struggle to win over the working class for the creation of a Popular front from below, by organizing and leading everyday struggle for satisfying everyday needs of the working class, such as the struggle against the costs of everyday existence, the struggle against the war, struggle for the freedom and democratic and national rights of the nationally oppressed working class of Yugoslavia”.

In October he arrived in Moscow, he was able to make

In October he arrived in Moscow, he was able to make

Pieck advised caution, repeating that the creation of a people’s government was impossible in the actual situation in the Balkans. Instead he pressed Tito to create a large movement capable of defending the independence of Yugoslavia and the right to self-determination of Yugoslav nations. On the other hand, the CPY should not advocate the defense of the present borders of Yugoslavia. Pieck suggested that Tito try to reach an agreement with bourgeois groups such as the Agrarian Party led by Dragoljub Jovanović.

He encouraged Tito to think about creating a large political movement against the war, for the defense of the independence of Yugoslavia and for good relations with theUSSR

Tito as Secretary-General

The Executive Committee addressed the issue of creating a people’s government:

“In

The Executive Committee addressed the issue of creating a people’s government:

“In

As for the strategy regarding the war in Europe, the position of the Comintern was shaped as follows :

“Under the action slogan of independence for the peoples of Yugoslavia, their right of self-determination and their mutual aid against any violence, the Party should develop propaganda in the masses and among citizens against the readiness of the bourgeoisie and the government to capitulate before the projects of German and Italian imperialism to dismantle Yugoslavia.

Yet, the Party should not put forward the slogan on the

Yet, the Party should not put forward the slogan on the

The Comintern position on the issue of the Popular Front strategy was rather more precise:

“The Party must make use of all occasions for cooperation with the elements of opposition and groups of opposition in the small bourgeoisie parties and with the forces inside the Social Democratic parties in order to widen, temporarily at least, the unified front against the reaction and for respecting the demands of the masses, as well as for the defence of the independence of Yugoslavia”.

After the defeat of France, and Hitler’s victory in Western Europe,

After the defeat of France, and Hitler’s victory in Western Europe,

Petrović was the last member of the CPY who went to Moscow to present the situation in Yugoslavia and subsequently bring back from Moscow instructions for the CPY. In the spring of 1944, Milovan Djilas was at last given the opportunity to travel to Moscow and establish direct contact with the Soviet leadership.

In the meantime, the communication was ensured via radio operated by

In the meantime, the communication was ensured via radio operated by

“The preservation of peace, the defense of national liberty and independence of Yugoslav peoples against the entrance of the said peoples in the war on the side of any belligerent imperialist party, because any link with any of the imperialist groups meant abandoning Yugoslavia’s independence.

The only way to effectively defend its independence and keep the

The only way to effectively defend its independence and keep the

Therefore the CPY was just a spectator when an officers’ coup overthrew the Cvetković-Maček government after it had joined the Tripartite Pact (agreement between Germany, Italy and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940) . The great demonstrations of March 27th in support of the coup were organized without any knowledge of the CPY. When late in the day its members joined the movement, the only slogan they put forth called for an alliance with the USSR. Not even the mass demonstrations provoked any changes in Tito’s strategy.

On the following day he wrote to the Comintern that the CPY would organize the people to resist German and Italian armed attack but would also fight against any British action that could induce Yugoslavia to join the war on its side. The CPY wanted the new government led by General Dušan Simović to quit the Pact and to conclude an alliance with the USSR.

In Croatia and in Bosnia-Herzegovina the Nazi’s established a puppet genocidal

In Croatia and in Bosnia-Herzegovina the Nazi’s established a puppet genocidal

Before the outbreak of the war, the Party had 8000 members and 30 000 members in the Communist Youth. One of the major elements of the CPY strategy in the preceding months was presented as follows:

“The struggle against reactionary governments which refused to grant the people

“The struggle against reactionary governments which refused to grant the people

In his article written in June 1941, Tito said that at the May meeting it was concluded that in the country existed a “revolutionary energy of the masses”; that was provoked by:

“Brutal occupation regime and the spoliation of the people; even more brutal oppression of certain nations and the hatred it provoked against its perpetrators; the treason of the ex-governing circles recruited from the bourgeoisie; the evidence of the criminal national and social policy of the defunct regime…”

The evocation of the need for a people’s government and of the existence of revolutionary energy showed that Tito began to think that the occupation may present an opportunity to use the imperialist war for starting a revolutionary movement that could bring about a people’s government.

He made no reference to this possibility in his telegrams to

He made no reference to this possibility in his telegrams to

The message that came from Moscow on the same day was urgent and perfectly clear. The CPY as well as other communist parties should create a single national Popular front and a common international Front to fight against German and Italian invaders since the attack on the USSR was not only a blow to the first Socialist country, but also an attack on the liberty and independence of all nations. The priorities ware also clearly defined.

During this stage of combat the CPY should fight for the

During this stage of combat the CPY should fight for the

Tito’s actions from the moment he became the acting head of

Tito’s actions from the moment he became the acting head of

The CPY was a section of the Comintern and acted as such as long as contact with Moscow existed. Tito and the CPY demonstrated a tendency to take initiative was the creation of a people’s government, that is to say an armed uprising against the Constitutional government of Yugoslavia. The will to take the power by arms was omnipresent in Tito’s thoughts even though he abandoned his plans each time Moscow told him to do so.

Tito and his partisans

Hitler’s attack and a series of defeats of the Red Army

Hitler’s attack and a series of defeats of the Red Army

Tito and the rank and file of the CPY were both convinced that the issue of the war would be solved by a victorious advance of the Red Army, which would triumphantly march into Yugoslavia. Therefore the real task of the CPY was to solve the issue of power and social revolution before its arrival. The war against Germany could not be won without the help of the Red Army, but the CPY had to win the fight for power in Yugoslavia on its own. Therefore, when in July the first partisan squads started operating in Serbia, their goal was to fight the occupying German troops and the local Serbian gendarmerie, but most of all to demonstrate that the Kingdom of Yugoslavia had disappeared once for all.

When eventually they entered small provincial towns in Serbia, the local

When eventually they entered small provincial towns in Serbia, the local

The purpose of this campaign was in fact to create people’s councils on the local level. Edward Kardelj, a Slovene communist and Tito’s second, explained in October 1941 that the Partisans had to replace the existing local administration because it served as loyal transmission of the occupation authorities. New forms of local administration were needed to mobilize the population for the fight against the Germans.

The tasks of people’s councils were to provide food and material

The tasks of people’s councils were to provide food and material

The new forms of local administration were not united in any sort of Partisans’ pyramid of power in 1941. Long after the end of the War, Tito explained that he had abstained from organizing local people’s councils into any sort of representative body on national level to avoid making problems for the USSR. In September 1941, he was informed that Moscow had re-established diplomatic relations with the Yugoslav government which had been exiled to London. Thus he abstained from forming a representative body, a sort of people’s government in Yugoslavia. Tito was aware that Moscow had in mind another policy when the Comintern invited the CPY to organize an armed uprising in Yugoslavia.

The theory of two phases called for an urgent alliance with

The theory of two phases called for an urgent alliance with

Mihailović could rely on the prestige of his rank and could

Mihailović could rely on the prestige of his rank and could

On the other hand, Tito’s partisans had virtually no political legitimacy because the presence of the CPY in the political life of Yugoslavia had been more than limited before the war. The only way Tito’s Partisans could gain credibility and political legitimacy was to be at the forefront of the battle with Germans.

Only by fighting the Germans, but primarily the entire local administration

Only by fighting the Germans, but primarily the entire local administration

Before they met for the first time in September 1941, Tito intentionally ignored all activity of Mihailović’s units in his reports to Moscow. He related only the operations of his troops, and stigmatized the collaboration of the volunteer units of Kosta Pećanac, who signed an agreement with local occupation authority. The first time Tito informed Moscow that Mihailović’s units were fighting the Germans was on 28 September, but he called them military Tchetniks without naming Mihailović.

Tito in fact mentioned Mihailović’s units only after he had met

Dimitrov’s demand for clarification arrived in December 1941 at the time

Dimitrov’s demand for clarification arrived in December 1941 at the time

Tito failed to inform Moscow of his new strategy but the

Tito failed to inform Moscow of his new strategy but the

The fundamental disagreement between Tito and his superiors in Moscow thus came to light. Tito refused to follow the strategy of “two phases”, since he broke off with Mihailović and started building his own political system. But the situation had changed because Moscow had no means of putting pressure to Tito. Their correspondence was filled with Moscow’s instructions to make peace with Mihailović so that the situation in Yugoslavia would not become an issue within the alliance with the US and UK.

Titos’s road to power

Tito, however, continued his own agenda of denouncing Mihailović to Moscow

Tito, however, continued his own agenda of denouncing Mihailović to Moscow

However, Tito’s refusal to follow the strategy of “two phases” remained an unresolved issue in Tito’s relations with Moscow. On 12 November 1942, Tito sent the following message to Moscow:

“We are now creating something like a government, and it will be called the National Committee for the Liberation of Yugoslavia (NKOJ). All Yugoslav nationalities and various ex-parties will take part in the Committee”.

Dimitrov’s response underlined the existing disagreements. He agreed with the creation

Dimitrov’s response underlined the existing disagreements. He agreed with the creation

“Do not confront it (NKOJ) with the Yugoslav government in London. At the present phase, you should not talk about abolishing the Monarchy. You should not put forward the slogan of creating a Republic. The issue of the political system in Yugoslavia, as you yourself understand, will be solved after the defeat of the Italo-German coalition and after the liberation of the country from occupation.... You should keep in mind that the USSR has established relations with the Yugoslav King and Government. Thus open confrontation with them would create difficulties for the common war effort of the USSR on one side and of the UK and US on the other side. You should consider the issue of your fight not only from the standpoint of your own national interest, but also in regard to the international Anglo-Soviet and American coalition”.

Dimitrov’s evocation of the “present phase” was an explicit reference to

Dimitrov’s evocation of the “present phase” was an explicit reference to

The scope of differences between Tito and the Soviet government was demonstrated by Moscow’s decision to dissolve the Comintern. In order to preserve the Alliance with Western powers, the Soviet government had put an end to the institution that governed the international communist movement. Nevertheless, Tito’s agenda remained the same, he still accorded overall priority to the communist conquest of power in Yugoslavia by fighting against Mihailović’s units. However, he managed to find another way of setting up a large antifascist front by establishing direct contact with the British Army. The first British liaison officers were parachuted to his Headquarters in May 1943. Tito regularly informed Dimitrov about his contacts with the British and later with American liaison officers too. Their reports heavily influenced the change of Allied strategy towards the Partisan movement.

The fate of Yugoslavia was sealed when Stalin and Roosevelt agreed

The fate of Yugoslavia was sealed when Stalin and Roosevelt agreed

Therefore Tito resolved the issue of anti-fascist front due to an US-Soviet agreement, and officially became the Allied Commander in Yugoslavia. Even before the decisions of the Tehran Conference reached Yugoslavia, he was confident enough to realize his project of creating of a people’s government.

The second session of the AVNO J, held in the town

The second session of the AVNO J, held in the town

Tito’s victory in the civil war in Yugoslavia had to be confirmed by replacement of the Royal Government in exile with NKOJ. That was the imperative condition for gaining international recognition for NKOJ and other institutions within the Partisan pyramid of power. During this process, the Soviet aid and counsel were of outmost importance. Moscow could not extend openly its political and diplomatic support to Partisans without provoking dissentions inside the Allied coalition. Nevertheless, the official Soviet propaganda and the Communist press in UK and US were openly militating in favour of Partisans. The issue of the political solution for the civil war in Yugoslavia had to be solved in direct contact between Tito and the UK and US governments.

Churchill wrote a personal letter to Tito in January 1944. In

Churchill wrote a personal letter to Tito in January 1944. In

Tito was not impressed by the contact on the highest level and repeated that the decisions of the Second meeting of Avnoj: the King cannot return in the country, the government in exile should be dissolved since NKOJ was the only legitimate government of Yugoslavia. His letter to Churchill was written on the same day he got instructions from Dimitrov saying that the Royal Government should be got rid of along with its Minister of War Mihailović. This kind of political solution of the Yugoslavia civil war was inacceptable for British government.

The only solution possible was, as Anthony Eden, British Minister of

The only solution possible was, as Anthony Eden, British Minister of

The stalemate was broken by the American proposal brought by Farish to Tito. The American intelligence service, OSS (Office of Secret Services) proposed the arrival of the Viceroy of Croatia, Ivan Šubašić, in Yugoslavia. He was supposed to facilitate the transfer of the majority of the members of the biggest Croatian pre-war party, Croatian Peasant party, to the Partisan side. This was the plan that Šubašić in the summer of 1943 proposed to OSS. It was now officially proposed to Tito, who made use of it in order to find a way out in his talks with British government. Tito already had information that Šubašić had approved off, on several occasion, the struggle of Partisans. This was the information that he got via Moscow from United States where Šubašić was living after the fall of Yugoslavia. Therefore Tito the creation of a transition government composed from Partisans representatives and some pre-war Yugoslav politicians, amongst which he proposed in the first place Šubašić.

Therefore, in the beginning of 1944 in direct contacts with Western

Therefore, in the beginning of 1944 in direct contacts with Western

The Tehran decisions thus were realized and the decisive Partisan victory

The Tehran decisions thus were realized and the decisive Partisan victory

Tito’s Yugoslavia almost singlehandedly defied the West on the issue of

Tito’s Yugoslavia almost singlehandedly defied the West on the issue of

The Yugoslav-Soviet crisis was presented as a political top-level conflict within

The Yugoslav-Soviet crisis was presented as a political top-level conflict within

Conclusion: The Stalin-Tito split

“This controversy was a matter of great importance for the internal

“This controversy was a matter of great importance for the internal

The Yugoslav-Soviet conflict was not provoked by ideological differences. It was

The Yugoslav-Soviet conflict was not provoked by ideological differences. It was

The explanations of the origins of Tito-Stalin split are to be found in the evolution of the CPY from 1937 onwards, and are intrinsically linked with the actions of Josip Broz Tito. He became a member of the Central Committee in 1934 and as such went to Moscow, only to inherit the actual leadership of the Party during the purges. He proved to be a true Stalinist leader since he never questioned any instructions he got from Moscow. If anything, he showed himself to be overzealous. On several occasions, Georgi Dimitrov had to explain to him that there was no chance a social revolution could successfully be carried out in Yugoslavia before the War.

The German attack on Yugoslavia did not incite Tito to act,

The German attack on Yugoslavia did not incite Tito to act,

Once they joined the war, Tito and the CPY started pursuing their own agenda – social revolution as a consequence of the victory in the Civil War they had waged against the Yugoslav King, the Royal Government, and their Minister of War in Yugoslavia – general Dragoljub, Draža, Mihailović. For Dimitrov and the Soviet authorities, Tito’s actions risked to provoke problems within the Allied coalition. Therefore he was reprimanded on several occasions, until the Partisan units under his command were recognized also by the Western Allies. The Partisan Army, and the state institutions that were created during the war gave his movement enough potential to be at the forefront of the conflicts in Trieste and in Greece which heralded in the Cold War. The conflict with Stalin was provoked by the same tendency of Tito’s to advance his own interests without consulting Moscow. The causes of the conflict were not ideological since Yugoslavia was the most faithful disciple of the USSR. They were in fact economic and geostrategic.

Tito’s peronnal file: Archives

Tito’s peronnal file: Archives

Мировой экономический кризис 1929 – 1933 гг. Пути выхода

Мировой экономический кризис 1929 – 1933 гг. Пути выхода Англия в XI-XIII вв.

Англия в XI-XIII вв.  Урок обществознания в 9 классе. Учитель – Зимин Дмитрий Николаевич, МБОУ СОШ №27, г. Новосибирск

Урок обществознания в 9 классе. Учитель – Зимин Дмитрий Николаевич, МБОУ СОШ №27, г. Новосибирск  Страны Восточной Европы после окончания второй мировой войны

Страны Восточной Европы после окончания второй мировой войны Царствование Николая I Павловича

Царствование Николая I Павловича Ледовое побоище

Ледовое побоище История как наука

История как наука Презентация Октябрьская революция 1917 года и её значение

Презентация Октябрьская революция 1917 года и её значение  Тема: «Русские земли под игом Золотой орды»

Тема: «Русские земли под игом Золотой орды» Трудом ковалась победа

Трудом ковалась победа Женщины, ковавшие Победу

Женщины, ковавшие Победу Повторительно-обобщающий урок: Становление Средневековой Европы

Повторительно-обобщающий урок: Становление Средневековой Европы 75 - летию Победы посвящается

75 - летию Победы посвящается Жены декабристов. Авторы презентации ученицы 10 класса МОУ СОШ №41 Ковальчук Мария, Кравцова Варвара. Руководитель проекта – Кор

Жены декабристов. Авторы презентации ученицы 10 класса МОУ СОШ №41 Ковальчук Мария, Кравцова Варвара. Руководитель проекта – Кор Александр Невский - к 800-летию со дня рождения

Александр Невский - к 800-летию со дня рождения Представление о Новейшей философии Шопенгауэр, Ницше

Представление о Новейшей философии Шопенгауэр, Ницше История театра: с древности до наших дней

История театра: с древности до наших дней Распространение Реформации в Европе

Распространение Реформации в Европе Пирамиды - тайна вечности

Пирамиды - тайна вечности Чухломичи - участники боевых действий в Афганистане

Чухломичи - участники боевых действий в Афганистане Холодная война

Холодная война Обряды и традиции русского народа

Обряды и традиции русского народа Радикальные политические партии России в начале ХХ века

Радикальные политические партии России в начале ХХ века Образование СССР. Национальная политика в 1920-е гг

Образование СССР. Национальная политика в 1920-е гг Іван Грозний

Іван Грозний Культурно-исторические аспекты сексуальности

Культурно-исторические аспекты сексуальности Культура Древней Греции

Культура Древней Греции Власть и общество в 1725-1800 гг

Власть и общество в 1725-1800 гг