Содержание

- 2. Background: Gastroschisis and omphalocele are among the most frequently encountered congenital anomalies in pediatric surgery. Combined

- 3. Background: Many babies have correctable lesions and simply require routine pediatric care. For others, the abdominal

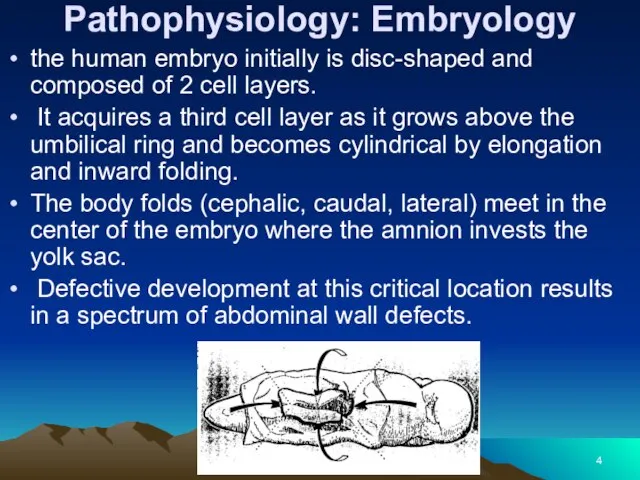

- 4. Pathophysiology: Embryology the human embryo initially is disc-shaped and composed of 2 cell layers. It acquires

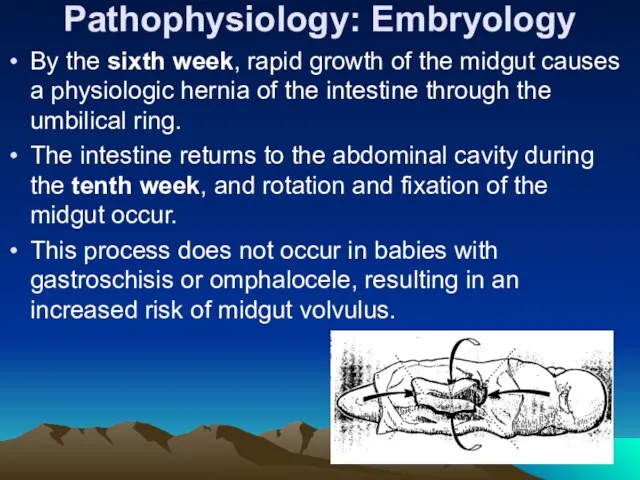

- 5. Pathophysiology: Embryology By the sixth week, rapid growth of the midgut causes a physiologic hernia of

- 6. Pathogenesis of omphalocele and gastroschisis Abdominal wall defects occur as a result of failure of the

- 7. Pathogenesis of Omphalocele In babies with omphalocele failure of central fusion at the umbilical ring by

- 8. Baby with an omphalocele.

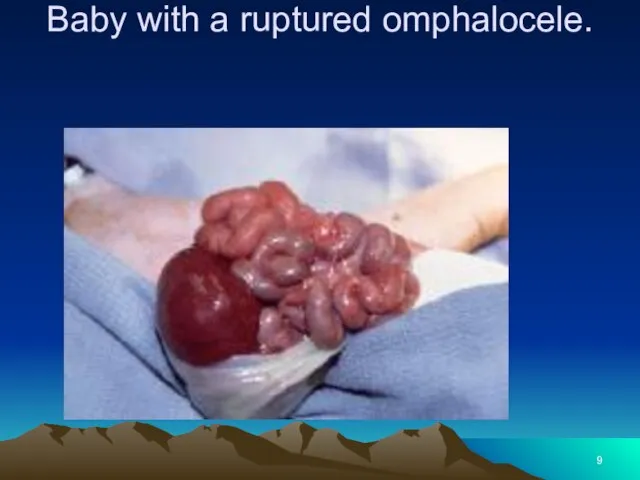

- 9. Baby with a ruptured omphalocele.

- 10. Pathogenesis of gastroschisis Possible explanations of the embryology of abdominal wall defect in gastroschisis include the

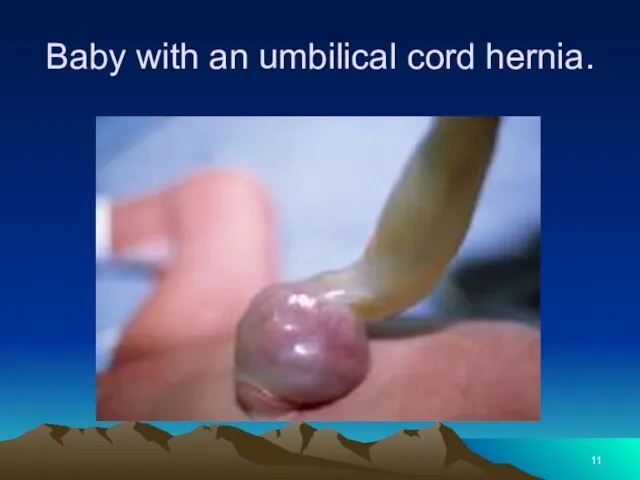

- 11. Baby with an umbilical cord hernia.

- 12. Frequency: In the US: Combined incidence of omphalocele and gastroschisis is 1 in 2000 births. Incidence

- 13. Mortality/Morbidity: Over the past 30 years, the survival rate of babies with gastroschisis and omphalocele has

- 14. Mortality/Morbidity: Long-term morbidity from gastroschisis is related to intestinal dysfunction and wound problems. Short gut syndrome

- 15. Mortality/Morbidity: Management of babies with short gut syndrome also has improved significantly as a result of

- 16. Mortality/Morbidity: Poor healing of the abdominal wound usually results in a ventral hernia, which may require

- 17. Mortality/Morbidity: Even with successful repair, which usually requires a synthetic patch, and good clinical outcome, the

- 18. CLINICAL Physical: Omphalocele In babies with omphaloceles, the size of the abdominal wall defect ranges from

- 19. CLINICAL Babies with the Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (ie, macroglossia, gigantism) have large, rounded facial features, hypoglycemia from

- 20. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome

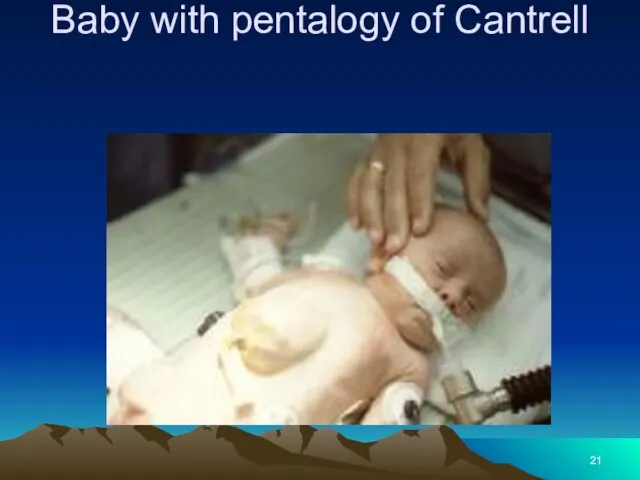

- 21. Baby with pentalogy of Cantrell

- 22. CLINICAL- Gastroschisis The defect is fairly uniform in size and location; a 5-cm vertical opening to

- 23. Baby with gastroschisis and associated intestinal atresia.

- 24. baby with gastroschisis and colon atresia.

- 25. Causes: Factors associated with high-risk pregnancies, such as maternal illness and infection, drug use, smoking, and

- 26. DIFFERENTIALS Other Problems to be Considered: In babies with omphalocele, a 35-80% incidence of other clinical

- 27. WORKUP Lab Studies: Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein Prenatal diagnosis of abdominal wall defects can be made by

- 28. WORKUP Imaging Studies: Fetal sonography may detect a genetic abnormality, with identification of a structural marker

- 29. TREATMENT Medical Care: Intestinal inflammation Intestinal inflammation may occur with either gastroschisis or ruptured omphalocele. The

- 30. TREATMENT Intact omphalocele Usually, neonates with intact omphalocele are in no distress, unless associated pulmonary hypoplasia

- 31. TREATMENT The omphalocele should be supported to avoid excessive traction to the mesentery. Give prophylactic antibiotics

- 32. TREATMENT Gastroschisis Respiratory distress in neonates with gastroschisis may respond to gastric decompression, although endotracheal intubation

- 33. TREATMENT-Surgical Care: Omphalocele Ambroise Pare, the 17th-century French surgeon, accurately described omphalocele and the dire consequences

- 34. TREATMENT-Surgical Care: Healing may be hastened by surgically mobilizing skin flaps sufficient to cover the omphalocele

- 35. TREATMENT-Surgical Care Gastroschisis In 1969, Allen and Wrenn adapted Schuster’s technique for treatment of gastroschisis. Silastic

- 36. TREATMENT-Surgical Care In addition, tight closure of the abdominal cavity impedes venous return to the heart,

- 37. Consultations: Neonatologists and pediatric surgeons usually care for babies with these anomalies. Consult with cardiology, pulmonology,

- 38. Diet: Babies with omphalocele usually do not require special formulas; their intestines are typically normal, with

- 39. Activity: A child with a repaired giant omphalocele has an epigastric liver. In this location, the

- 40. FOLLOW-UP Further Inpatient Care: Omphalocele Babies with omphalocele usually have rapid return of intestinal function after

- 41. FOLLOW-UP Gastroschisis Even if primary closure of the abdominal wall defect is obtained, a period of

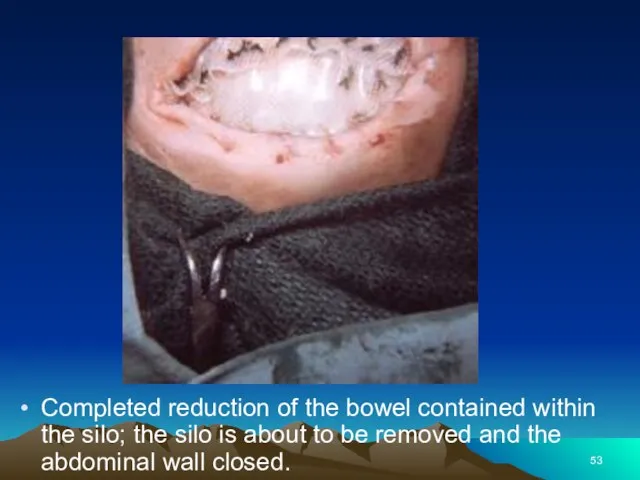

- 42. Silo closure of a baby with gastroschisis.

- 43. FOLLOW-UP Further Outpatient Care: After hospital discharge, babies require close follow-up care to assess growth and

- 44. FOLLOW-UP Transfer: The best way to treat the exposed intestines of a baby with gastroschisis who

- 45. The patient’s condition improved dramatically once closure of the abdominal cavity was achieved. Again, the author

- 46. Prognosis: Omphalocele Prognosis is dependent upon the severity of the associated problems. Babies with omphalocele are

- 47. Prognosis Gastroschisis Prognosis is dependent mainly upon severity of associated problems, including prematurity, intestinal atresia, short

- 48. Patient Education: Instruct parents regarding the significance of bilious (green) vomiting, since these babies may develop

- 49. Special Concerns: Prenatal care and planning With increased availability of sonography, prenatal diagnosis is more frequent.

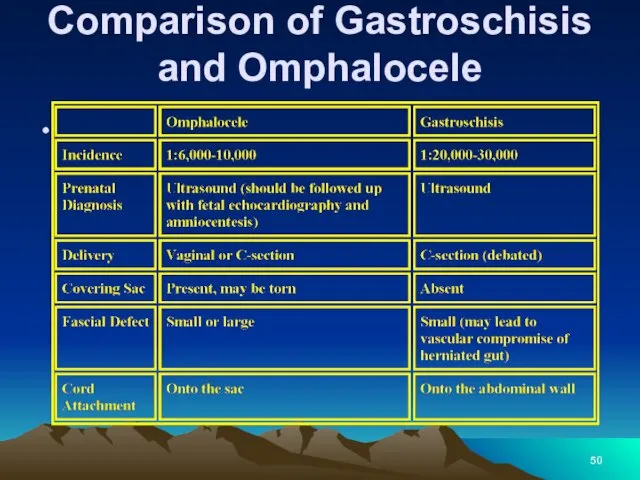

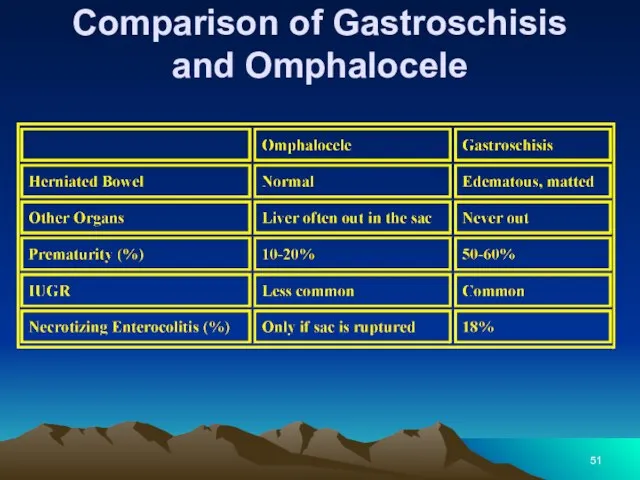

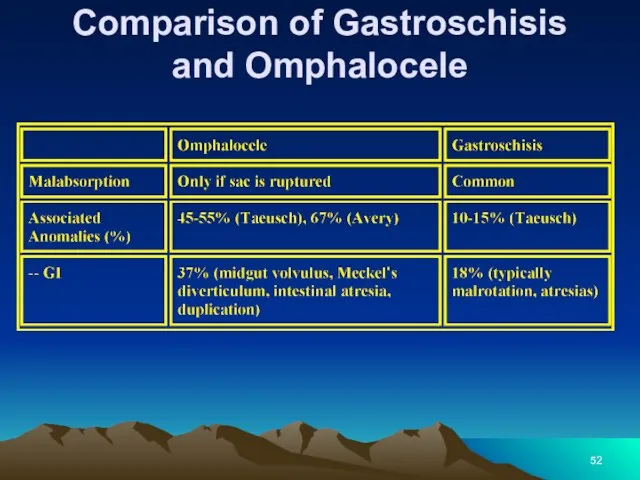

- 50. Comparison of Gastroschisis and Omphalocele

- 51. Comparison of Gastroschisis and Omphalocele

- 52. Comparison of Gastroschisis and Omphalocele

- 53. Completed reduction of the bowel contained within the silo; the silo is about to be removed

- 54. Baby with a giant omphalocele.

- 55. Same patient as in slide 54. Closure of the giant omphalocele using a synthetic patch.

- 56. Same patient as in slides 54-55. Tightening the abdominal wall closure

- 57. Same patient as in slides 54-56. Flank flaps were used to close the giant omphalocele in

- 59. Скачать презентацию

Основы помповой инсулинотерапии

Основы помповой инсулинотерапии Острый аппендицит у детей

Острый аппендицит у детей Наследственные болезни человека

Наследственные болезни человека Диагноз: вторичное частичное отсутствие зубов

Диагноз: вторичное частичное отсутствие зубов Зарядка для глаз

Зарядка для глаз Заболевания мочевыводящих путей у беременных

Заболевания мочевыводящих путей у беременных Нарушения внимания при локальных поражениях мозга

Нарушения внимания при локальных поражениях мозга Бешенство. Вирус бешенства

Бешенство. Вирус бешенства Reflexes

Reflexes Хронический фиброзный периодонтит. Особенности клинического течения и диагностики

Хронический фиброзный периодонтит. Особенности клинического течения и диагностики ВІЛ-інфекція Історія відкриття. Етіологія. Епідеміологія. Патогенез. Клінічні прояви

ВІЛ-інфекція Історія відкриття. Етіологія. Епідеміологія. Патогенез. Клінічні прояви Эндовидеохирургия

Эндовидеохирургия Созылмалы өкпе текті жүрек

Созылмалы өкпе текті жүрек Малярия

Малярия Уақытша еңбекке жарамсыздық

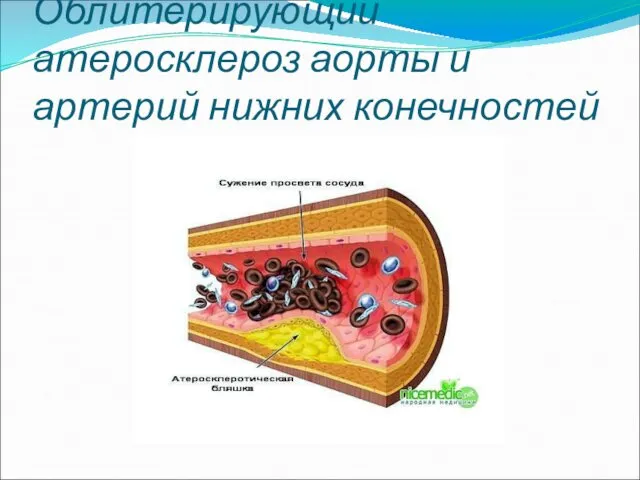

Уақытша еңбекке жарамсыздық Облитерирующий атеросклероз аорты и артерий нижних конечностей

Облитерирующий атеросклероз аорты и артерий нижних конечностей Остановка сердца

Остановка сердца Становление естественнонаучных знаний в эпоху Возрождения

Становление естественнонаучных знаний в эпоху Возрождения Лекарственные средства, влияющие на функции органов дыхания

Лекарственные средства, влияющие на функции органов дыхания Охрана окружающей среды как мера профилактики заболеваний органов дыхания

Охрана окружающей среды как мера профилактики заболеваний органов дыхания Неврологиялық қарау әдістері

Неврологиялық қарау әдістері Идиопатический анкилозирующий спондилоартрит (болезнь Бехтерева)

Идиопатический анкилозирующий спондилоартрит (болезнь Бехтерева) Тератогенные факторы. Фармакологические тератогенны

Тератогенные факторы. Фармакологические тератогенны Развитие гемоперикарда при чрескожном коронарном вмешательстве

Развитие гемоперикарда при чрескожном коронарном вмешательстве Физическое воспитание ребенка первого года жизни

Физическое воспитание ребенка первого года жизни Методы лучевой диагностики в неврологии

Методы лучевой диагностики в неврологии Жатырдың тусуі

Жатырдың тусуі Реанимация новорожденных (программа реанимации новорожденных)

Реанимация новорожденных (программа реанимации новорожденных)