Содержание

- 2. Introduction A little exercise in interviewing Please interview your neighbour about the issues, and then introduce

- 3. Qualitative and Quantitative Research “There's no such thing as qualitative data. Everything is either 1 or

- 4. Quantitative and Qualitative „In many social sciences, quantitative orientations are often given more respect. This may

- 5. Some aspects of Qualitative Research Qualitative research is concerned with developing explanations of social phenomena. It

- 6. Some misperceptions about qualitative research Misperceptions Qualitative research means you just interview people. Qualitative research is

- 7. What are the learning goals of this module?

- 8. Learning goals of this module This module aims to enable you to understand the theoretical foundations

- 9. Qualitative Research in Practice Case of wildlife conservation in Jammu and Kashmir, India Doctoral Research by

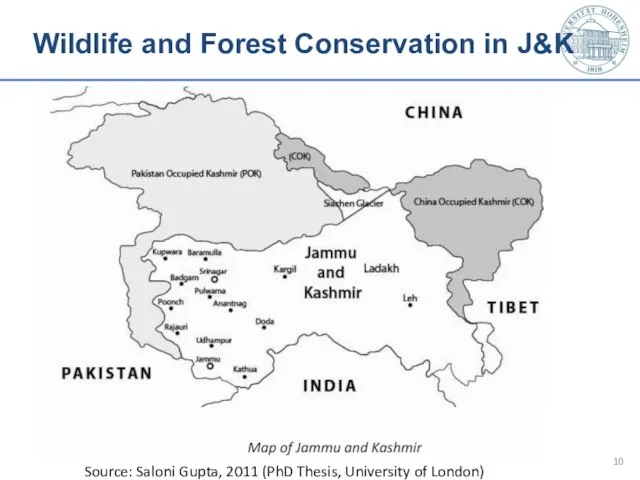

- 10. Wildlife and Forest Conservation in J&K Source: Saloni Gupta, 2011 (PhD Thesis, University of London)

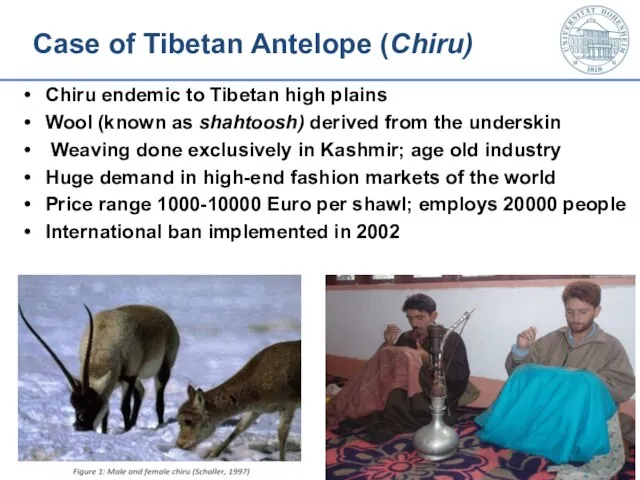

- 11. Case of Tibetan Antelope (Chiru) Chiru endemic to Tibetan high plains Wool (known as shahtoosh) derived

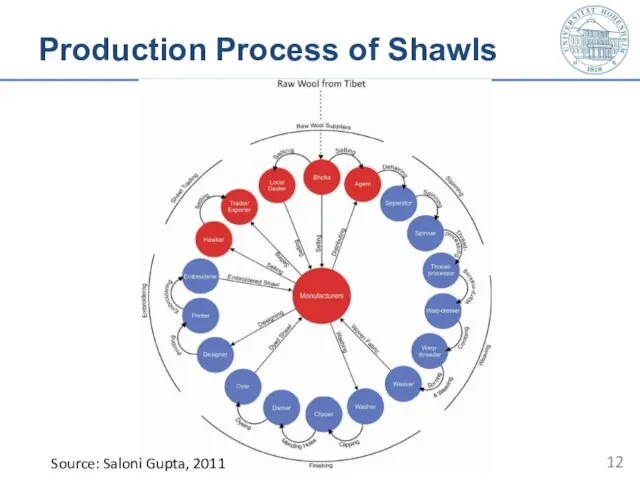

- 12. Production Process of Shawls Source: Saloni Gupta, 2011

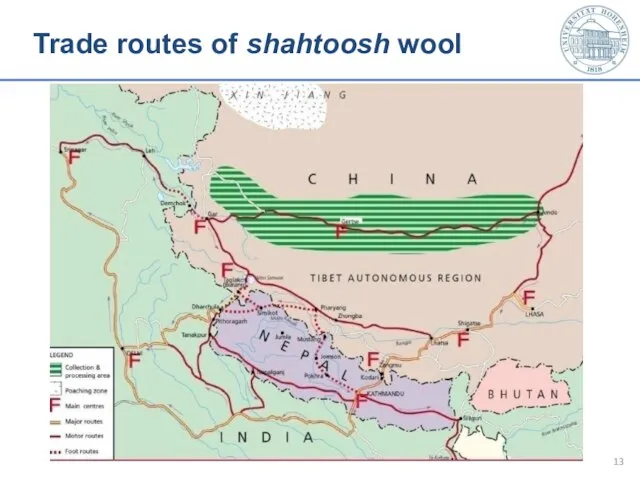

- 13. Trade routes of shahtoosh wool

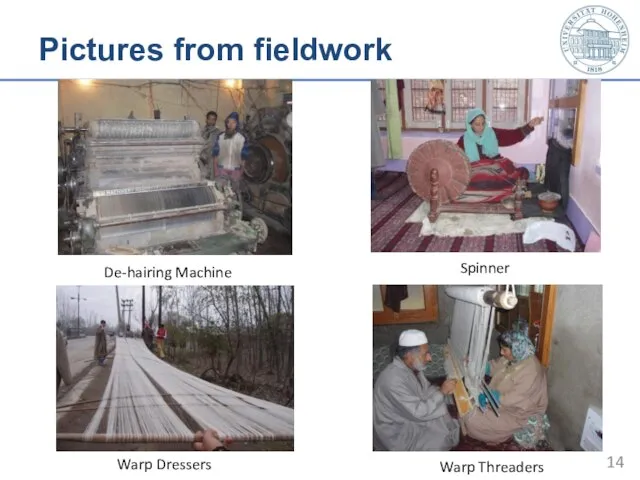

- 14. Pictures from fieldwork De-hairing Machine Spinner Warp Threaders Warp Dressers

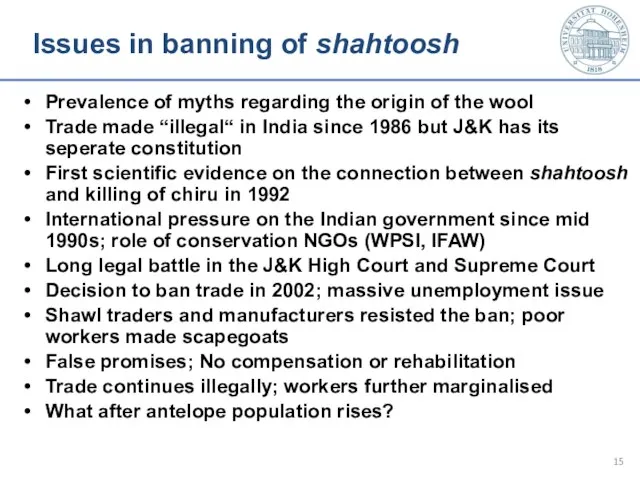

- 15. Issues in banning of shahtoosh Prevalence of myths regarding the origin of the wool Trade made

- 16. Some questions for discussion... The research objective is to understand the process of banning of Shahtoosh,

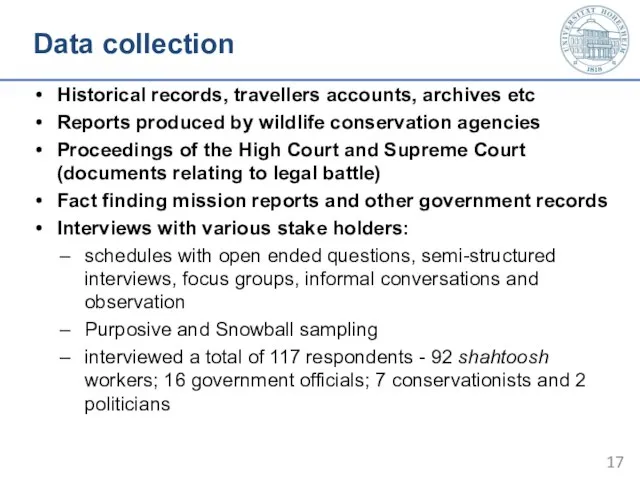

- 17. Data collection Historical records, travellers accounts, archives etc Reports produced by wildlife conservation agencies Proceedings of

- 18. Description of fieldwork period Stage 1: Building up contacts, personal setup and initial interviews with workers

- 19. Description of fieldwork period Stage 2: Interviews with state actors and local NGOs Understanding the ´´split´´

- 20. History of Shawl Industry Origin of shawl industry (14th century) State owned workshops (karkhanas) developed under

- 21. Legal Status of Chiru Listed in Appendix 1 of CITES, making trade illegal Listed as “endangered”

- 22. Ban on Shahtoosh: chronology of events Late 1980s: CITES and wildlife conservation NGOs began creating awareness

- 23. Split role of the state? Party politics being played by two important political outfits in Kashmir

- 24. Excerpts from interviews: politics of banning “As long as I am the Chief Minister, shahtoosh will

- 25. Perpetuation of myths post-ban Excerpts from interviews: “Ban on shahtoosh is not justifiable as it based

- 26. Differential Impact of Ban Different categories of workers have experienced differential impacts Shahtoosh workers are left

- 27. Excerpts from interviews: Differential Impact of Ban “Before the ban, I was respected in my locality.

- 28. ‘Delegated Illegality’ Poverty and lack of alternative employment opportunities are not the only determining factors for

- 29. Excerpts from interviews: rehabilitation “I have heard that the School is providing training to the shawl

- 30. Conclusions Global concern for wildlife conservation is justifiable but matching accountability towards affected communities is missing

- 31. Conclusions Political climate of state largely shapes manner in which nature conservation interventions experienced by affected

- 32. Categories and concepts emerging from data Sustainability for whom? Split role of the state Differential impact

- 33. Second Example Joint Forest Management in Jammu and Kashmir

- 34. Joint Forest Management (JFM) in J&K Rationale: Forest conservation can not be undertaken without support and

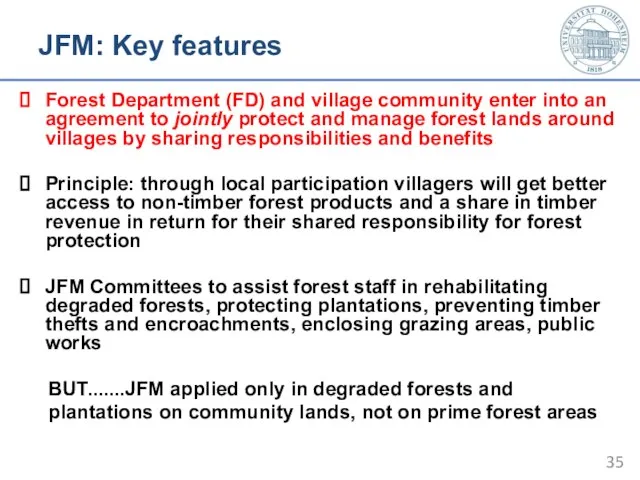

- 35. JFM: Key features Forest Department (FD) and village community enter into an agreement to jointly protect

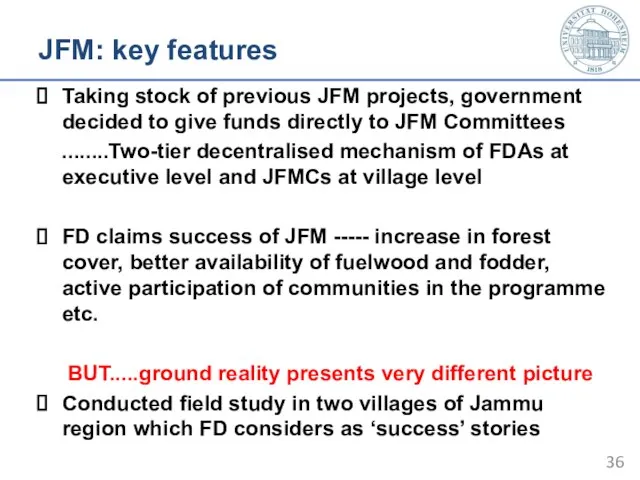

- 36. JFM: key features Taking stock of previous JFM projects, government decided to give funds directly to

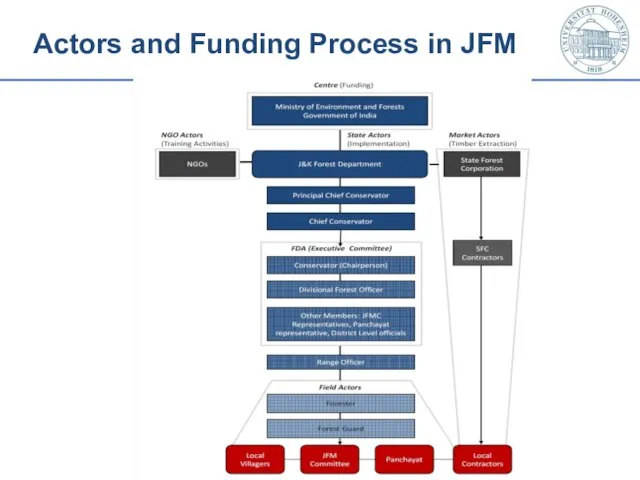

- 37. Actors and Funding Process in JFM

- 38. Ground reality of JFM From Centralisation to Decentralisation: Do blockages disappear? JFM Committees not elected but

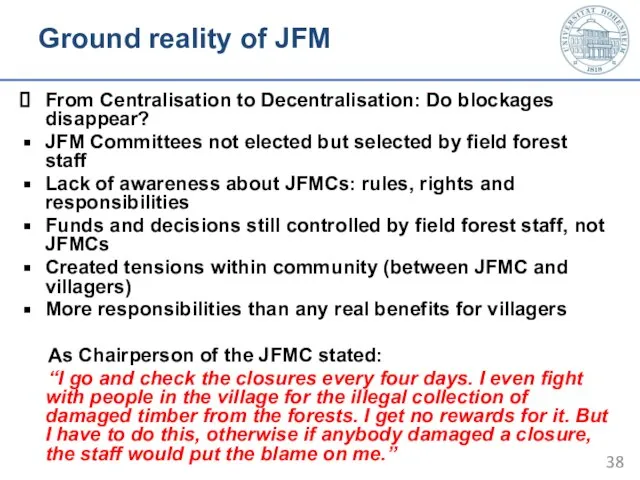

- 39. Increased Biomass, Reduced Access FD mainly grows timber species rather than those more useful for villagers

- 40. Information asymmetries and corruption Information asymmetries between FD and villagers ------ opportunity for field-staff to bolster

- 41. Split-role of Field-staff Dilemmas faced by forest guard with regard to Forest regulations vis-a-vis local needs

- 42. Illegal Timber Felling An interview with forest guard: “In Mantalai, a few months back, BSF personnel

- 43. Illegal Timber Felling An interview with a village resident: “Most of our forests are being destroyed

- 45. Скачать презентацию

Токарно-винторезный станок 250 АТ.Ф1

Токарно-винторезный станок 250 АТ.Ф1 Для Нади

Для Нади Стратегия_инвестирования_в_криптовалюты_часть_2

Стратегия_инвестирования_в_криптовалюты_часть_2 Презентация Русские народные инструменты

Презентация Русские народные инструменты Современный клиент

Современный клиент С новым годом, ти- трейд

С новым годом, ти- трейд Результат

Результат Узоры на крыльях бабочки

Узоры на крыльях бабочки Monster high. Монстры

Monster high. Монстры Презентация1

Презентация1 Афиша на А 3 (для редактирования)

Афиша на А 3 (для редактирования) Вход Господень в Иерусалим. (Вербное воскресение)

Вход Господень в Иерусалим. (Вербное воскресение) ВАЗОНЫ 2022 (1)

ВАЗОНЫ 2022 (1) Фасад ресторана

Фасад ресторана Мультимедийное оборудование в профессиональной деятельности

Мультимедийное оборудование в профессиональной деятельности Кинокомпания - Ты и Я. Личный фотоальбом

Кинокомпания - Ты и Я. Личный фотоальбом Форсунки паровых котлов

Форсунки паровых котлов Ручные швейные работы

Ручные швейные работы Физкультминутка: Морское путешествие

Физкультминутка: Морское путешествие Космические коммунисты.1 этап

Космические коммунисты.1 этап Vebinar_Proekt_vnedrenia_ERP_-_rerayt_2

Vebinar_Proekt_vnedrenia_ERP_-_rerayt_2 Вимірювання потужності i напруженості поля надзвичайно високочастотних (НВЧ) сигналів. (Тема 12.2)

Вимірювання потужності i напруженості поля надзвичайно високочастотних (НВЧ) сигналів. (Тема 12.2) Книга рекордов факультета

Книга рекордов факультета Управдом. Предложения по упорядочиванию оказания услуг по отоплению

Управдом. Предложения по упорядочиванию оказания услуг по отоплению Microsoft PowerPoint Presentation (1)

Microsoft PowerPoint Presentation (1) Прицепы и полуприцепы тракторные

Прицепы и полуприцепы тракторные Германия

Германия Профессия писатель

Профессия писатель