Содержание

- 2. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Externalities, Open Access, and Public Goods In this chapter,

- 3. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Externalities Externality The direct effect of the actions of

- 4. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Externalities Externalities may either help or harm others. An

- 5. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. The inefficiency of competition with externalities Competitive firms and

- 6. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. The inefficiency of competition with externalities Private cost The

- 7. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Supply-and-Demand Analysis We use a supply-and-demand diagram to illustrate

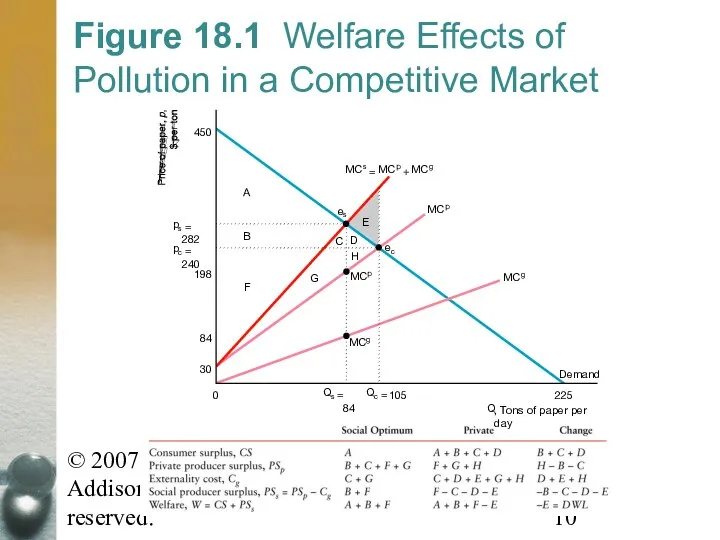

- 8. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.1 Welfare Effects of Pollution in a Competitive

- 9. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.1 Welfare Effects of Pollution in a Competitive

- 10. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.1 Welfare Effects of Pollution in a Competitive

- 11. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Supply-and-Demand Analysis The figure illustrates two main results with

- 12. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Reducing Externalities Because competitive markets produce too many negative

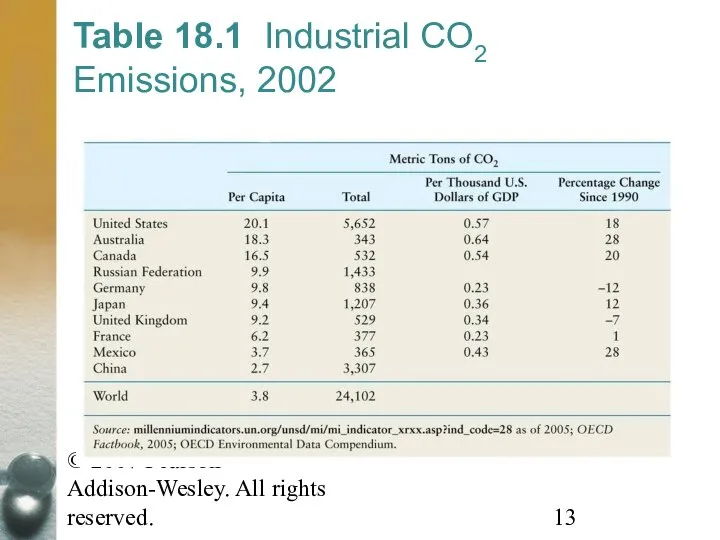

- 13. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Table 18.1 Industrial CO2 Emissions, 2002

- 14. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Reducing Externalities If a government has sufficient knowledge about

- 15. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Reducing Externalities A governmental limit on the amount of

- 16. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Reducing Externalities Internalize the externality To bear the cost

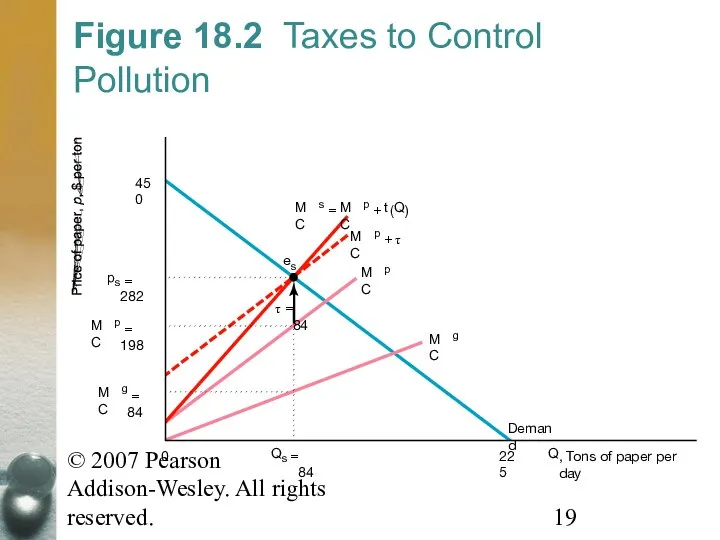

- 17. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.2 Taxes to Control Pollution Placing a tax

- 18. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.2 Taxes to Control Pollution Alternatively, applying a

- 19. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.2 Taxes to Control Pollution Demand MC p

- 20. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Cost-Benefit Analysis By using a cost-benefit analysis, we obtain

- 21. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Cost-Benefit Analysis Welfare is maximized by reducing output and

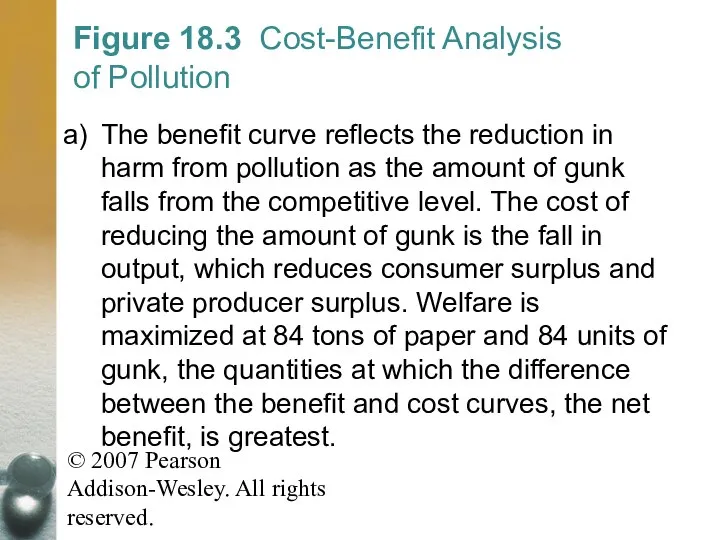

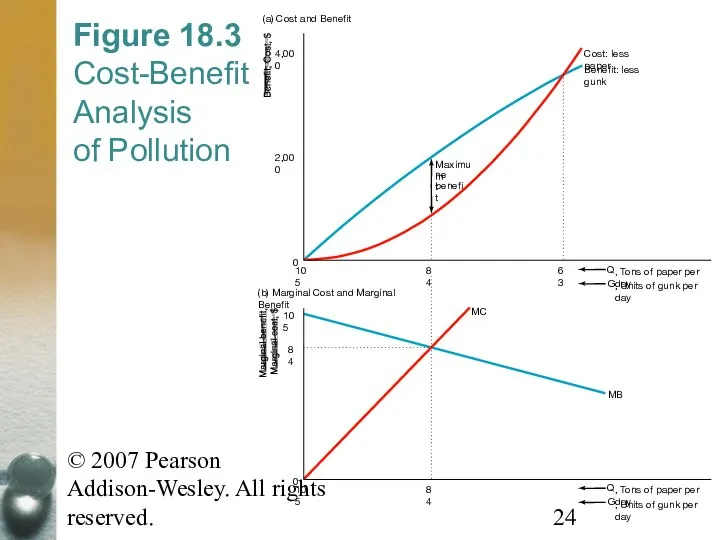

- 22. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.3 Cost-Benefit Analysis of Pollution The benefit curve

- 23. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.3 Cost-Benefit Analysis of Pollution The net benefit

- 24. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.3 Cost-Benefit Analysis of Pollution Cost: less paper

- 25. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Market Structure and Externalities Two of our main results

- 26. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Monopoly and Externalities Although the competitive market with an

- 27. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Monopoly and Externalities Which effect dominates depends on the

- 28. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Monopoly Versus Competitive Welfare with Externalities In the absence

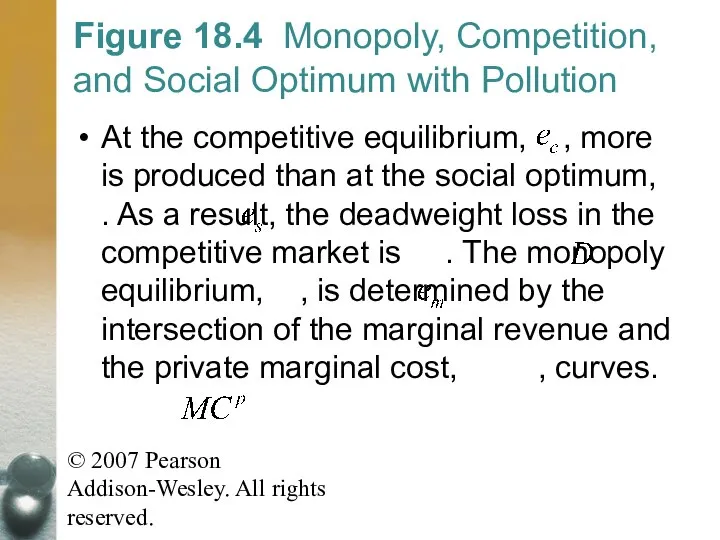

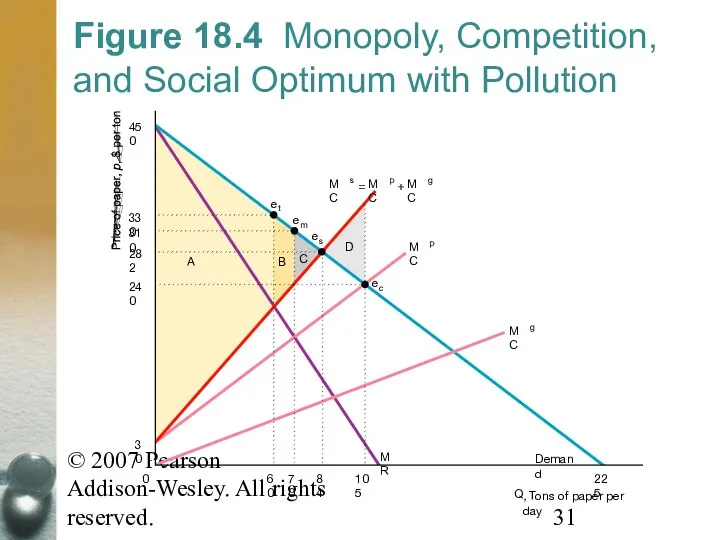

- 29. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.4 Monopoly, Competition, and Social Optimum with Pollution

- 30. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.4 Monopoly, Competition, and Social Optimum with Pollution

- 31. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.4 Monopoly, Competition, and Social Optimum with Pollution

- 32. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Taxing Externalities in Noncompetitive Markets Trying to solve a

- 33. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Taxing Externalities in Noncompetitive Markets To achieve a social

- 34. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Allocating Property Rights to Reduce Externalities Instead of controlling

- 35. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Allocating Property Rights to Reduce Externalities If no one

- 36. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Allocating Property Rights to Reduce Externalities For many bads,

- 37. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Coase Theorem According to the Coase Theorem (Coase, 1960),

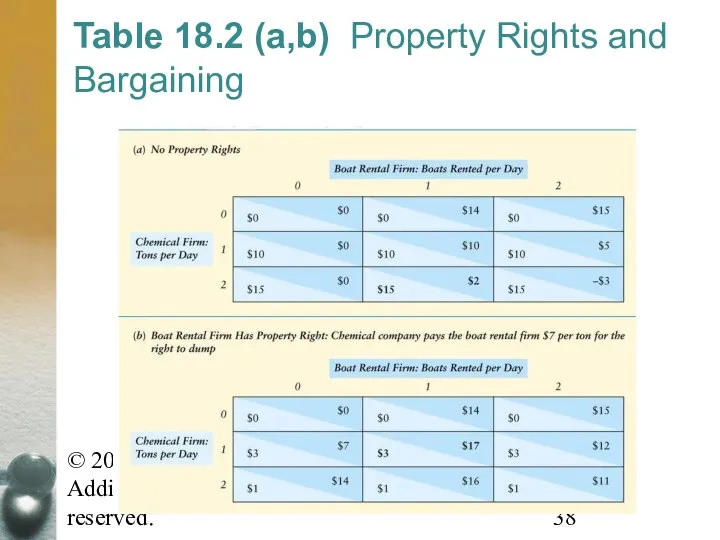

- 38. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Table 18.2 (a,b) Property Rights and Bargaining

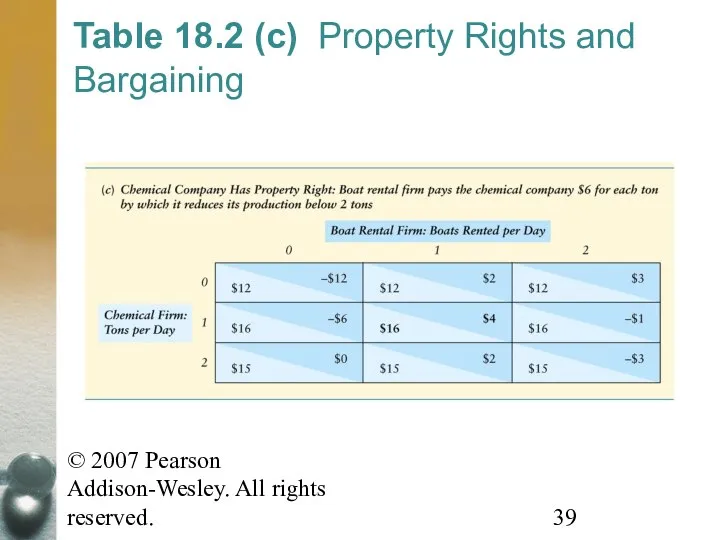

- 39. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Table 18.2 (c) Property Rights and Bargaining

- 40. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Coase Theorem If there are no impediments to bargaining,

- 41. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Coase Theorem Who gets the property rights affects the

- 42. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Problems with the Coase Approach First, if transaction costs

- 43. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Markets for Pollution If high transaction costs preclude bargaining,

- 44. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Markets for Pollution Under this cap and trade system,

- 45. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Markets for Pollution Bu using a market, the government

- 46. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Open-Access Common Property Open-Access Common Property Resources to which

- 47. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Overuse of Open-Access Common Property Because people do not

- 48. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Solving the Commons Problem Government Regulation of Commons Overuse

- 49. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Solving the Commons Problem Government Regulation of Commons Alternatively,

- 50. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Solving the Commons Problem Assigning Property Rights An alternative

- 51. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Public Goods Public Good A commodity or service whose

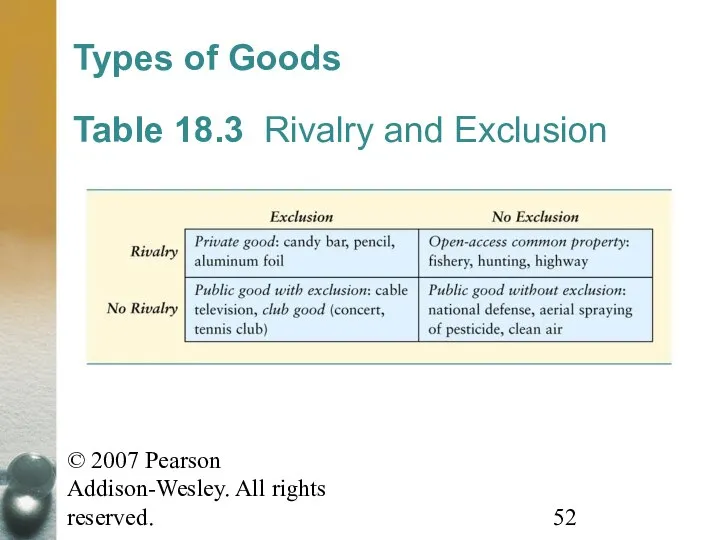

- 52. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Table 18.3 Rivalry and Exclusion Types of Goods

- 53. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Markets for public goods exist only if nonpurchasers can

- 54. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Demand for Public Goods Because a public good lacks

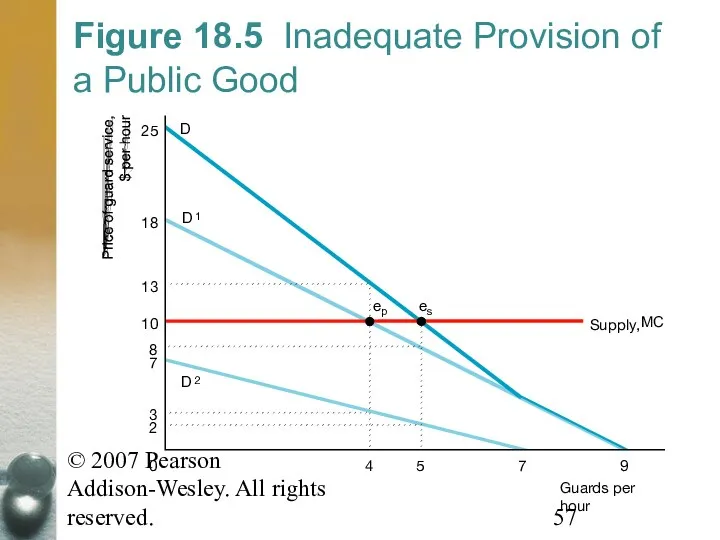

- 55. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.5 Inadequate Provision of a Public Good Security

- 56. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.5 Inadequate Provision of a Public Good Thus

- 57. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Figure 18.5 Inadequate Provision of a Public Good Guards

- 58. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Free Riding Many people are unwilling to pay for

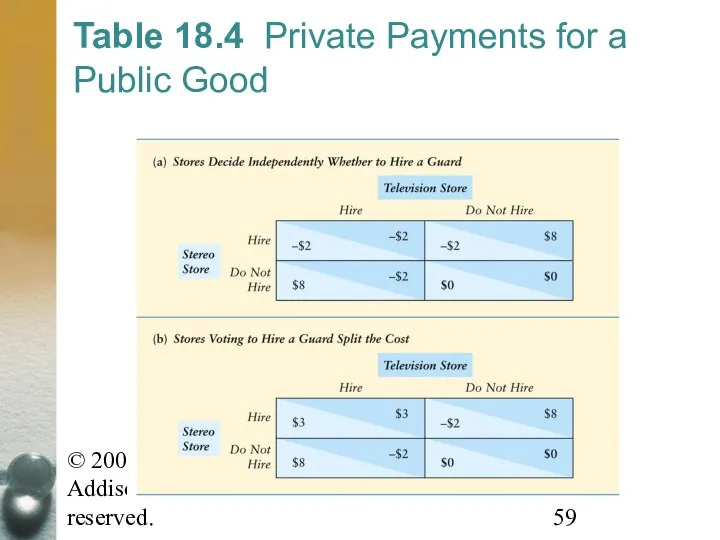

- 59. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Table 18.4 Private Payments for a Public Good

- 60. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Free Riding In each of these games, the Nash

- 61. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Reducing Free Riding Governmental or other collective actions can

- 62. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Valuing Public Goods To ensure that a nonexclusive public

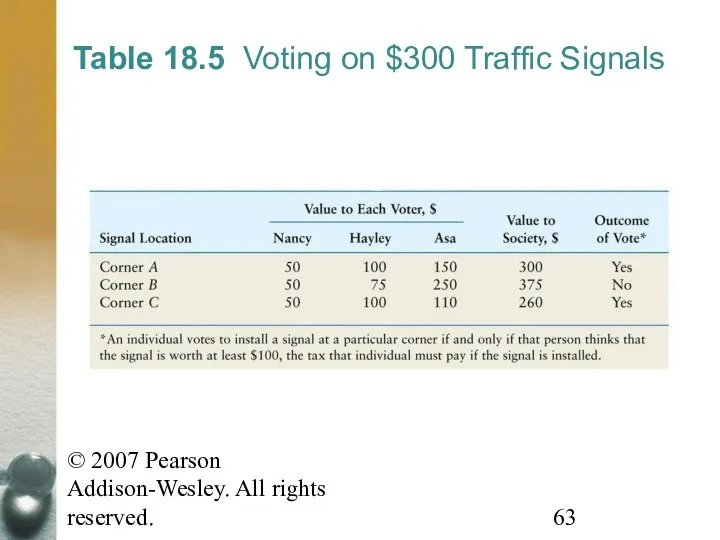

- 63. © 2007 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. Table 18.5 Voting on $300 Traffic Signals

- 65. Скачать презентацию

Внешнеторговая политика и роль государства в ее регулировании

Внешнеторговая политика и роль государства в ее регулировании Человек и техника. Проблемы и перспективы взаимодействия

Человек и техника. Проблемы и перспективы взаимодействия Теория предельных предельных продуктов и микроэкономическая модель предприятия. Издержки производства и прибыль

Теория предельных предельных продуктов и микроэкономическая модель предприятия. Издержки производства и прибыль Производственная и организационная структуры предприятия. (Тема 2)

Производственная и организационная структуры предприятия. (Тема 2) Теория прав собственности

Теория прав собственности Обмен, торговля, реклама

Обмен, торговля, реклама Российская империя

Российская империя Информационное обеспечение комплексного экономического анализа

Информационное обеспечение комплексного экономического анализа Глобальные проблемы человечества и геополитические процессы

Глобальные проблемы человечества и геополитические процессы Занятость и безработица

Занятость и безработица Человек и экономика. Ограниченность и выбор как основные понятия экономической науки

Человек и экономика. Ограниченность и выбор как основные понятия экономической науки Экономика. Теория отраслевых рынков

Экономика. Теория отраслевых рынков Разработка и внедрение системы учета количественно-качественных характеристик продукции ЗАО «Содружество-Соя»

Разработка и внедрение системы учета количественно-качественных характеристик продукции ЗАО «Содружество-Соя» Теория организации

Теория организации Территориальный орган Федеральной службы государственной статистики по Курской области

Территориальный орган Федеральной службы государственной статистики по Курской области Конвент. Роль учёта, анализа и аудита в защите Public Interest

Конвент. Роль учёта, анализа и аудита в защите Public Interest Экономика России в ситеме международного разделения труда

Экономика России в ситеме международного разделения труда Собственность и ее место в экономической системе. Модели экономических систем. Рыночная экономика

Собственность и ее место в экономической системе. Модели экономических систем. Рыночная экономика Anticrisis organization

Anticrisis organization Экономическая социализация молодежи

Экономическая социализация молодежи Управление государственными финансами и регулирование финансовых рынков

Управление государственными финансами и регулирование финансовых рынков Tasks Forcasting methods. The rule of min costs

Tasks Forcasting methods. The rule of min costs Объединенное народнохозяйственное товарищество

Объединенное народнохозяйственное товарищество Анализ персонала, заработной платы и производительности труда на предприятии

Анализ персонала, заработной платы и производительности труда на предприятии Анализ национальной и конфессиональной политики в Республике Коми

Анализ национальной и конфессиональной политики в Республике Коми Рыночная экономика. Рыночные отношения в экономике

Рыночная экономика. Рыночные отношения в экономике მენეჯერული სტატისტიკა. შერჩევა და შერჩევის განაწილება. თავი 7

მენეჯერული სტატისტიკა. შერჩევა და შერჩევის განაწილება. თავი 7 Экономика отрасли

Экономика отрасли