Содержание

- 2. THE FIRST CANADIAN CULTURES ARE CONSIDERED TO BE THE DORSET AND THULE CULTURES (THESE ARE ARCHAEOLOGICAL

- 3. DORSET CULTURE The Dorset was a Paleo-Eskimo culture, lasting from 500 BC to between AD 1000

- 4. The Dorset were first identified as a separate culture in 1925. The Dorset appear to have

- 5. In 1925 anthropologist Diamond Jenness received some odd artifacts from Cape Dorset. As they were quite

- 6. HISTORY The origins of the Dorset people are not well understood. They may have developed from

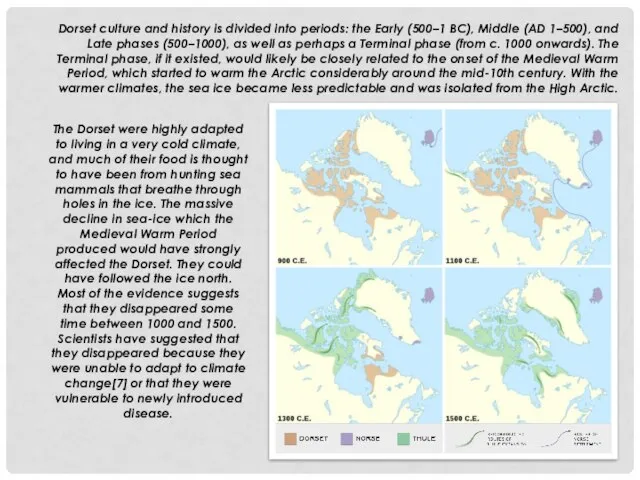

- 7. Dorset culture and history is divided into periods: the Early (500–1 BC), Middle (AD 1–500), and

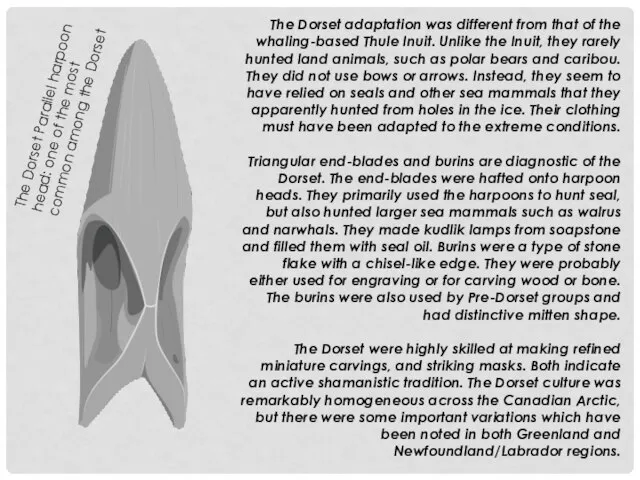

- 8. The Dorset adaptation was different from that of the whaling-based Thule Inuit. Unlike the Inuit, they

- 9. There appears to be no genetic connection between the Dorset and the Thule who replaced them.

- 10. THULE CULTURE Thule culture, prehistoric culture that developed along the Arctic coast in northern Alaska, possibly

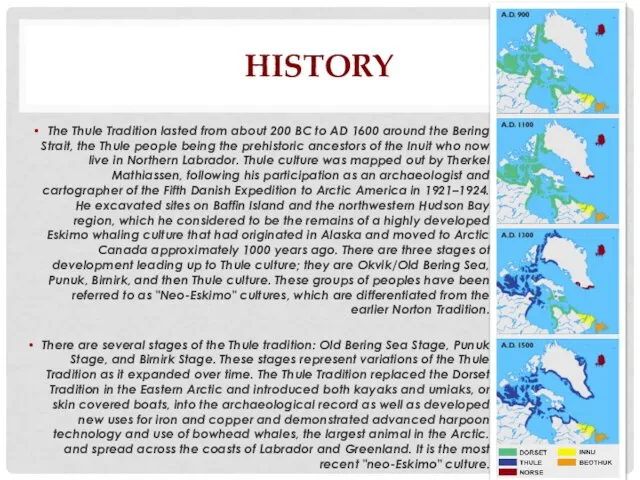

- 11. HISTORY The Thule Tradition lasted from about 200 BC to AD 1600 around the Bering Strait,

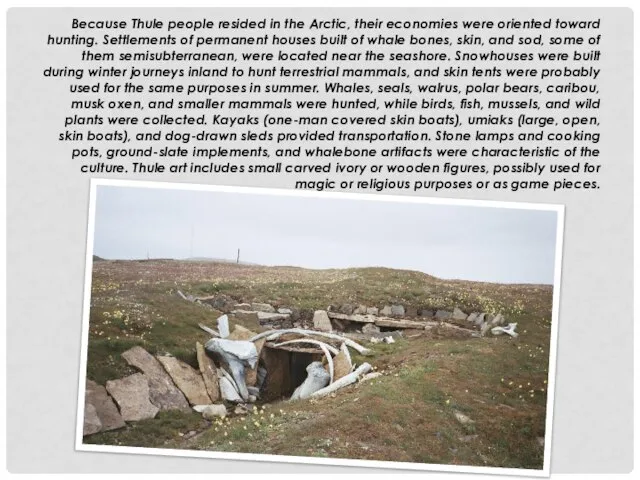

- 12. Because Thule people resided in the Arctic, their economies were oriented toward hunting. Settlements of permanent

- 14. Скачать презентацию

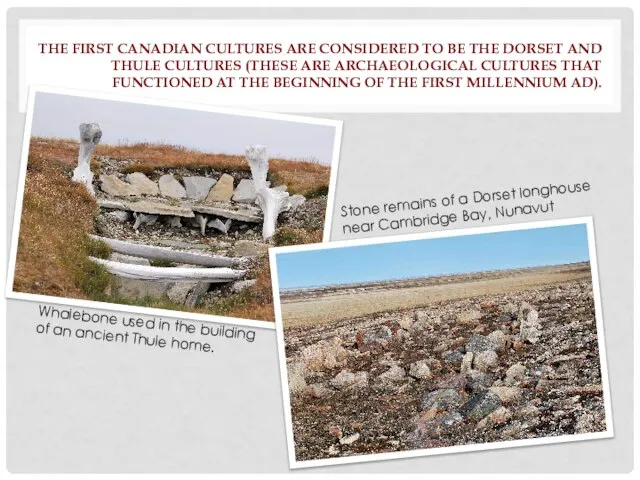

THE FIRST CANADIAN CULTURES ARE CONSIDERED TO BE THE DORSET AND

THE FIRST CANADIAN CULTURES ARE CONSIDERED TO BE THE DORSET AND

Whalebone used in the building of an ancient Thule home.

Stone remains of a Dorset longhouse near Cambridge Bay, Nunavut

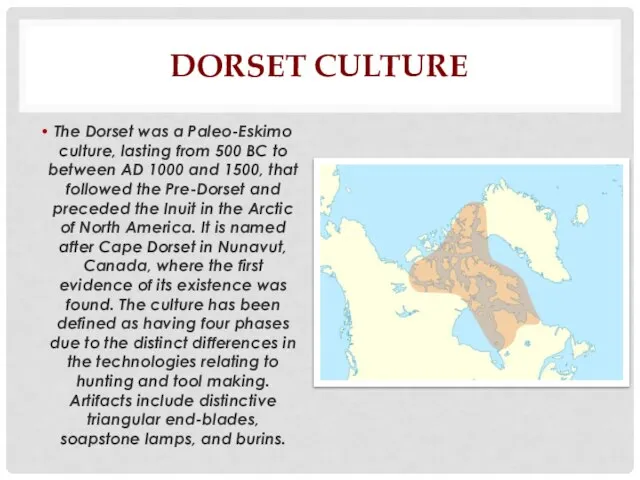

DORSET CULTURE

The Dorset was a Paleo-Eskimo culture, lasting from 500 BC

DORSET CULTURE

The Dorset was a Paleo-Eskimo culture, lasting from 500 BC

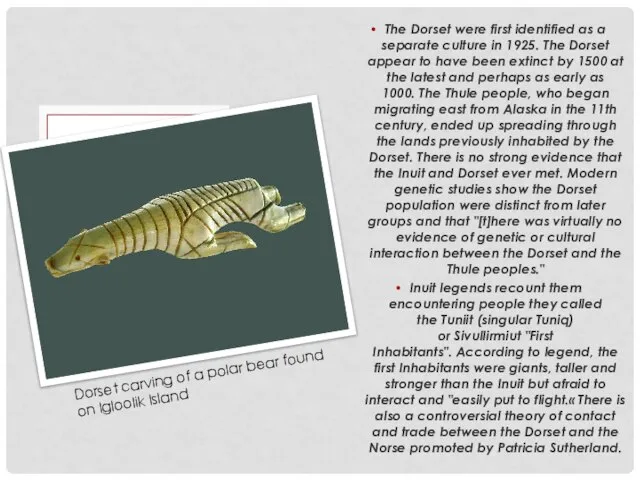

The Dorset were first identified as a separate culture in 1925. The

The Dorset were first identified as a separate culture in 1925. The

Inuit legends recount them encountering people they called the Tuniit (singular Tuniq) or Sivullirmiut "First Inhabitants". According to legend, the first Inhabitants were giants, taller and stronger than the Inuit but afraid to interact and "easily put to flight.« There is also a controversial theory of contact and trade between the Dorset and the Norse promoted by Patricia Sutherland.

Dorset carving of a polar bear found on Igloolik Island

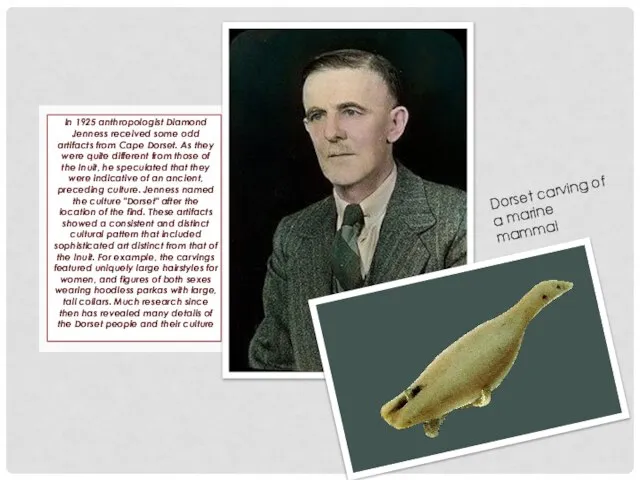

In 1925 anthropologist Diamond Jenness received some odd artifacts from Cape

In 1925 anthropologist Diamond Jenness received some odd artifacts from Cape

Dorset carving of a marine mammal

HISTORY

The origins of the Dorset people are not well understood. They

HISTORY

The origins of the Dorset people are not well understood. They

Stylized ivory amulet from the Dorset culture, found in Labrador or Quebec, Canada

Dorset culture and history is divided into periods: the Early (500–1

Dorset culture and history is divided into periods: the Early (500–1

The Dorset were highly adapted to living in a very cold climate, and much of their food is thought to have been from hunting sea mammals that breathe through holes in the ice. The massive decline in sea-ice which the Medieval Warm Period produced would have strongly affected the Dorset. They could have followed the ice north. Most of the evidence suggests that they disappeared some time between 1000 and 1500. Scientists have suggested that they disappeared because they were unable to adapt to climate change[7] or that they were vulnerable to newly introduced disease.

The Dorset adaptation was different from that of the whaling-based Thule

The Dorset adaptation was different from that of the whaling-based Thule

Triangular end-blades and burins are diagnostic of the Dorset. The end-blades were hafted onto harpoon heads. They primarily used the harpoons to hunt seal, but also hunted larger sea mammals such as walrus and narwhals. They made kudlik lamps from soapstone and filled them with seal oil. Burins were a type of stone flake with a chisel-like edge. They were probably either used for engraving or for carving wood or bone. The burins were also used by Pre-Dorset groups and had distinctive mitten shape.

The Dorset were highly skilled at making refined miniature carvings, and striking masks. Both indicate an active shamanistic tradition. The Dorset culture was remarkably homogeneous across the Canadian Arctic, but there were some important variations which have been noted in both Greenland and Newfoundland/Labrador regions.

The Dorset Parallel harpoon head: one of the most common among the Dorset

There appears to be no genetic connection between the Dorset and

There appears to be no genetic connection between the Dorset and

Archaeological and legendary evidence is often thought to support some cultural contact, but this has been questioned. The Thule, for instance, engaged in seal-hole hunting, a method which requires several steps and includes the use of dogs. The Thule apparently did not use this technique in the time they had previously spent in Alaska. Settlement pattern data has been used to claim that the Dorset also extensively used a breathing-hole sealing technique and perhaps they would have taught this to the Inuit. But this has been questioned on the grounds that there is no evidence that the Dorset had dogs.

Some elders describe peace with an ancient group of people, while others describe conflict.

The Sadlermiut were a people living in near isolation mainly on and around Coats Island, Walrus Island, and Southampton Island in Hudson Bay up until 1902–03. Encounters with Europeans and exposure to infectious disease caused the deaths of the last members of the Sadlermiut.

However a subsequent 2012 genetic analysis showed no genetic link between the Sadlermiut and the Dorset.

THULE CULTURE

Thule culture, prehistoric culture that developed along the Arctic coast

THULE CULTURE

Thule culture, prehistoric culture that developed along the Arctic coast

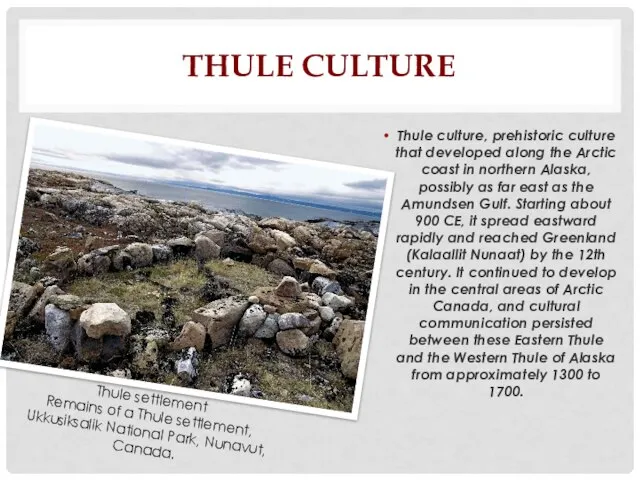

Thule settlement

Remains of a Thule settlement, Ukkusiksalik National Park, Nunavut, Canada.

HISTORY

The Thule Tradition lasted from about 200 BC to AD 1600

HISTORY

The Thule Tradition lasted from about 200 BC to AD 1600

There are several stages of the Thule tradition: Old Bering Sea Stage, Punuk Stage, and Birnirk Stage. These stages represent variations of the Thule Tradition as it expanded over time. The Thule Tradition replaced the Dorset Tradition in the Eastern Arctic and introduced both kayaks and umiaks, or skin covered boats, into the archaeological record as well as developed new uses for iron and copper and demonstrated advanced harpoon technology and use of bowhead whales, the largest animal in the Arctic. and spread across the coasts of Labrador and Greenland. It is the most recent "neo-Eskimo" culture.

Because Thule people resided in the Arctic, their economies were oriented

Because Thule people resided in the Arctic, their economies were oriented

Основные приёмы резания тонколистового металла и проволоки

Основные приёмы резания тонколистового металла и проволоки Разработка технологии производства анизотропной стали

Разработка технологии производства анизотропной стали Lektsia_2015_2

Lektsia_2015_2 джотто

джотто Котоматограф или Синемяу

Котоматограф или Синемяу 20161112_literaturnoe_kraevedenie

20161112_literaturnoe_kraevedenie Женский день

Женский день 20170131_master-klass_na_konkurs

20170131_master-klass_na_konkurs Marktwirtschaft

Marktwirtschaft Цеосит

Цеосит 20161204_prezentatsiya_vavilon

20161204_prezentatsiya_vavilon Справочная система нормативно- правовых, нормативно-технических документов

Справочная система нормативно- правовых, нормативно-технических документов ИЖ - город новых стандартов. Архитектурно-градостроительная концепция

ИЖ - город новых стандартов. Архитектурно-градостроительная концепция Челябинская готеприимность

Челябинская готеприимность О нас. С любовью. Феррари. Фото

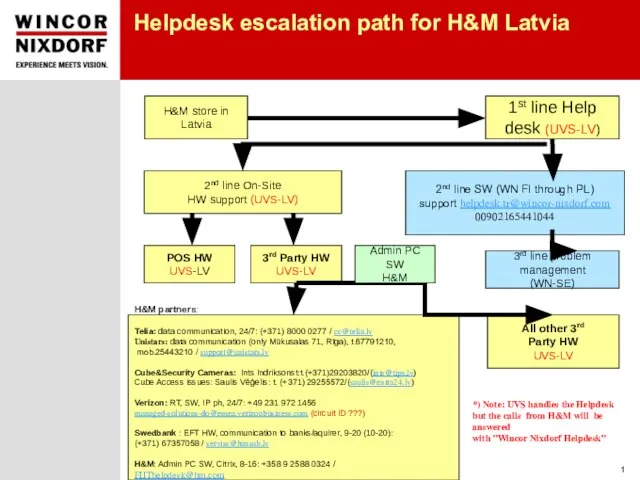

О нас. С любовью. Феррари. Фото HM_LV_EscalationPaths

HM_LV_EscalationPaths Влажно - тепловая обработка швейных изделий

Влажно - тепловая обработка швейных изделий श्री रुद्रम् Sri Rudram, ведический гимн, посвящённый Рудре

श्री रुद्रम् Sri Rudram, ведический гимн, посвящённый Рудре Процессоры. Центральный процессор

Процессоры. Центральный процессор Заповеди православной культуры

Заповеди православной культуры Восстание Спартака

Восстание Спартака Состав слова. Разбор слов по составу

Состав слова. Разбор слов по составу Производство медицинских изделий. Компания ООО Сатурн

Производство медицинских изделий. Компания ООО Сатурн Мен топ жетекшісімін

Мен топ жетекшісімін Возникновение земледелия и животноводства

Возникновение земледелия и животноводства Полиграфия

Полиграфия 20130120_bylina_skazaniya_istoricheskaya_pesnya_powerpoint

20130120_bylina_skazaniya_istoricheskaya_pesnya_powerpoint Igra_dlya_5_klassov

Igra_dlya_5_klassov