Содержание

- 2. Lecture 2. Plan The Main Historic Events of the Period. Old English Alphabet and Pronunciation. English

- 3. 1. The Main Historic Events of the Period.

- 4. British History Timeline The Celtic Period (the 5th century BC – 43 AD); Roman Britain (43

- 5. Celtic People The Celts immigrated to England in the 5th century B.C. and drove out the

- 6. The Romans In 43 A.D., an army of 40,000 Roman soldiers invaded Celtic Britain and made

- 7. The Main Historic Figures Julius Caesar (100BC - 44BC) Caesar was a politician and general of

- 8. The End of Roman Rule 410 A.D. The Romans started pulling soldiers from Britain in 410

- 9. The Jutes Come to Britain Vortigern (Вортигерн), a Celtic chieftain, asked the Jutes, a Germanic tribe,

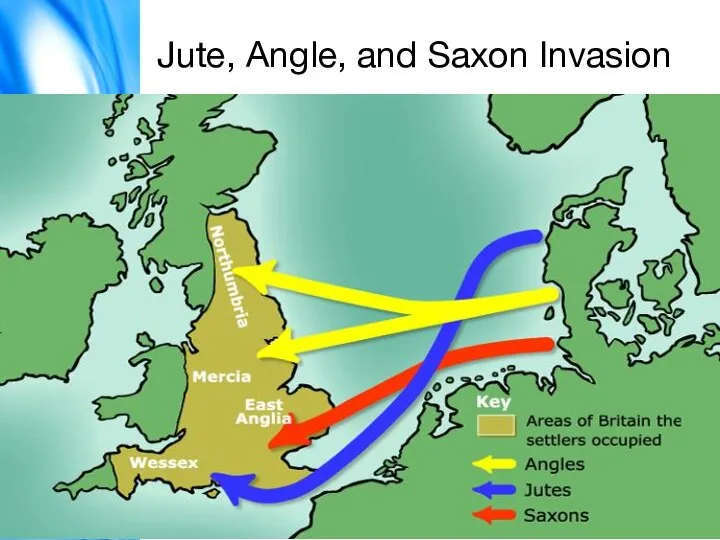

- 10. The start of the Germanic Tribes’ Invasion The Germanic Angle and Saxon tribes also invaded Britain.

- 11. Jute, Angle, and Saxon Invasion

- 12. The 7 kingdoms formed by the newcomers were the following: Jutes – the kingdom of Kent;

- 13. The Scandinavian Invasion Around 878 AD Danes and Norsemen, also called Vikings, invaded the country and

- 14. The Introduction of Christianity The arrival of St. Augustine in 597 and the introduction of Christianity

- 15. Alfred the Great (849 AD - 899 AD) King of the southern Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex

- 16. The Dialects spoken by the Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Frisians Northumbrian (нортумбрийский); Mercian (мерсийский); Kentish (кентийский); West-Saxon

- 17. The Available Texts Kentish (кентийский): The Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Latin: Historia ecclesiastica gentis

- 18. The Available Texts Mercian (мерсийский): Six Mercian hymns are included in the Anglo-Saxon glosses to the

- 19. 2. Old English Alphabet and Pronunciation.

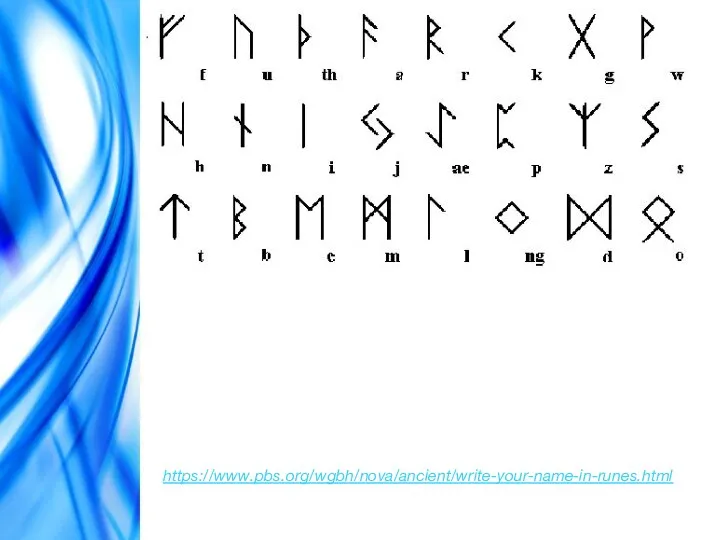

- 20. The Runes The runes are the letters in a set of related alphabets known as runic

- 21. They were of specific shape, designed to be cut on the wooden sticks, and only few

- 23. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ancient/write-your-name-in-runes.html

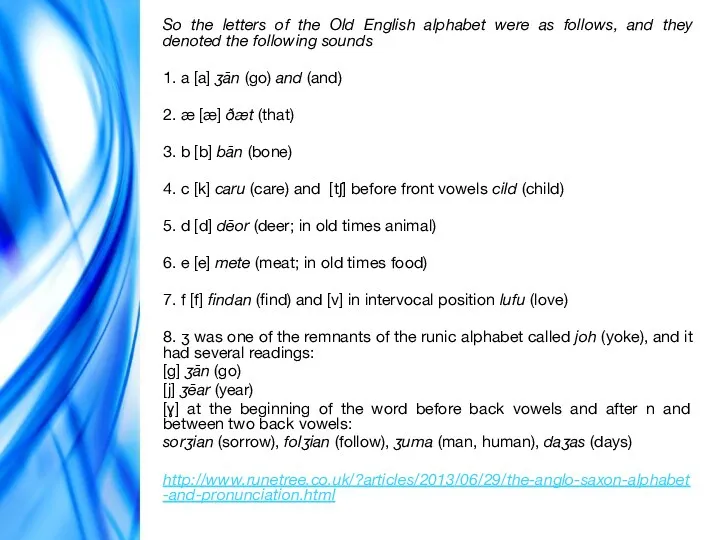

- 24. So the letters of the Old English alphabet were as follows, and they denoted the following

- 25. 9. h [h] hām (home), him (him), huntoð (hunting) 10. i [ɪ] hit (it), him (him),

- 26. 3. English Sounds as Compared with the Sounds in Other Indo-European Languages. Grimm’s Law. Verner’s Law.

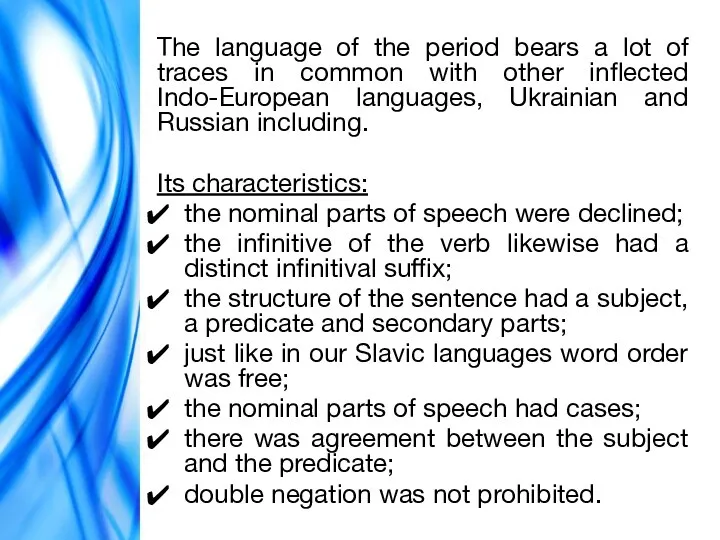

- 27. The language of the period bears a lot of traces in common with other inflected Indo-European

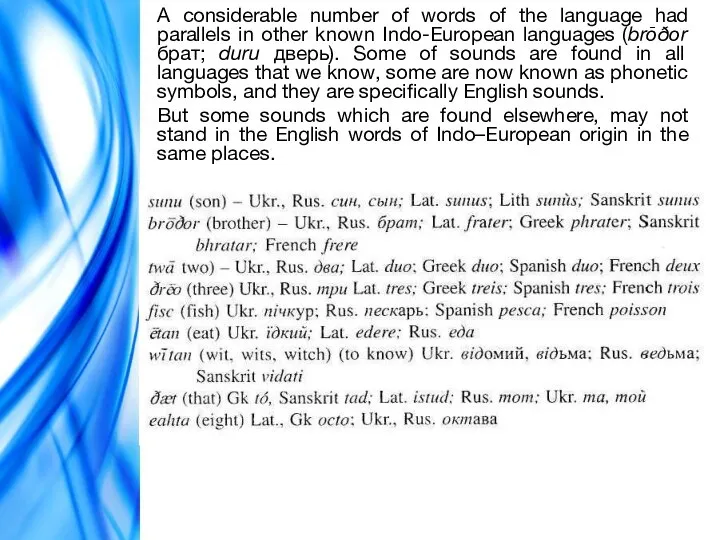

- 28. A considerable number of words of the language had parallels in other known Indo-European languages (brōðor

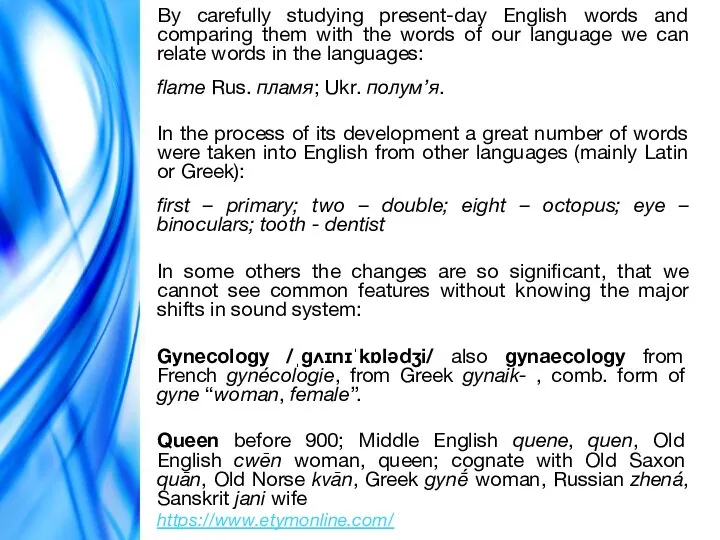

- 29. By carefully studying present-day English words and comparing them with the words of our language we

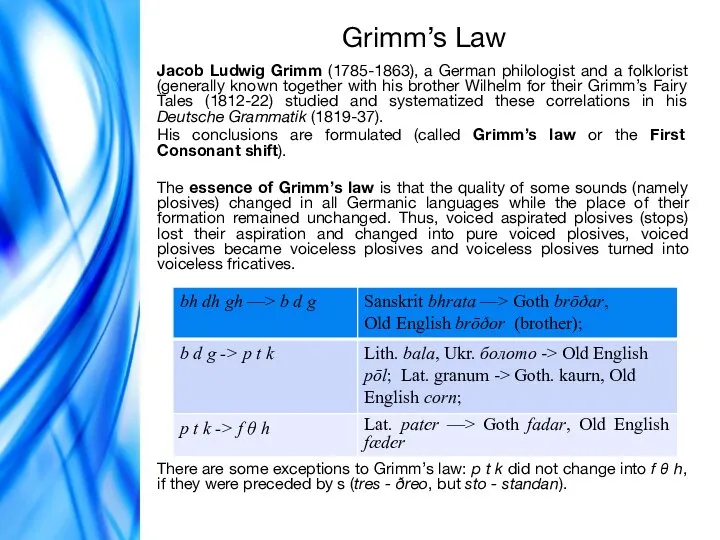

- 30. Grimm’s Law Jaсob Ludwig Grimm (1785-1863), a German philologist and a folklorist (generally known together with

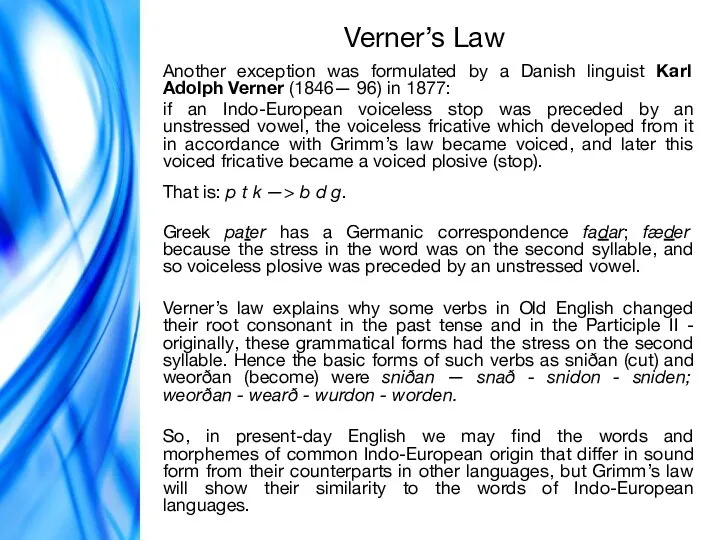

- 31. Verner’s Law Another exception was formulated by a Danish linguist Karl Adolph Verner (1846— 96) in

- 32. 4. The System of Vowels in Old English.

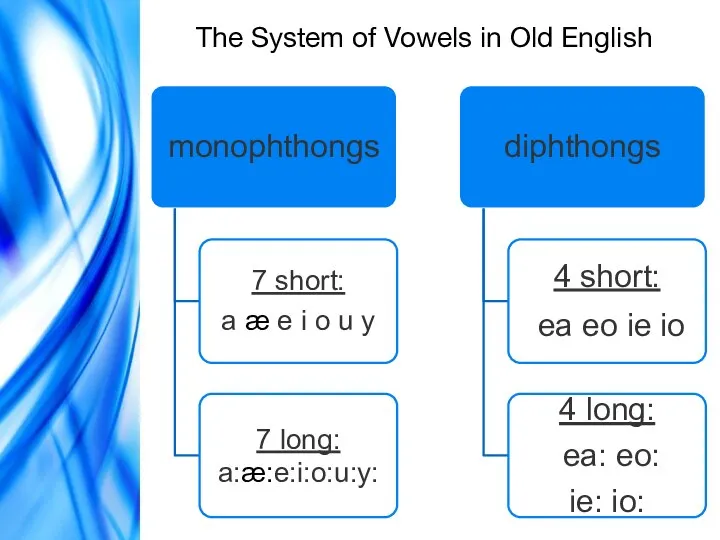

- 33. The System of Vowels in Old English

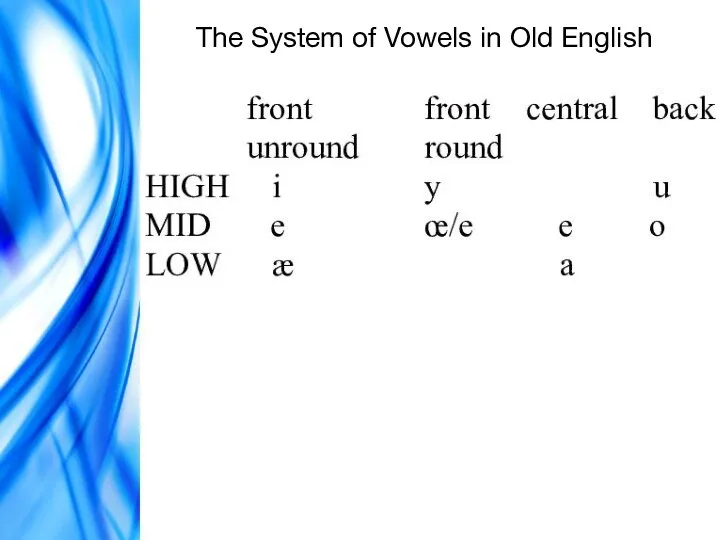

- 34. The System of Vowels in Old English

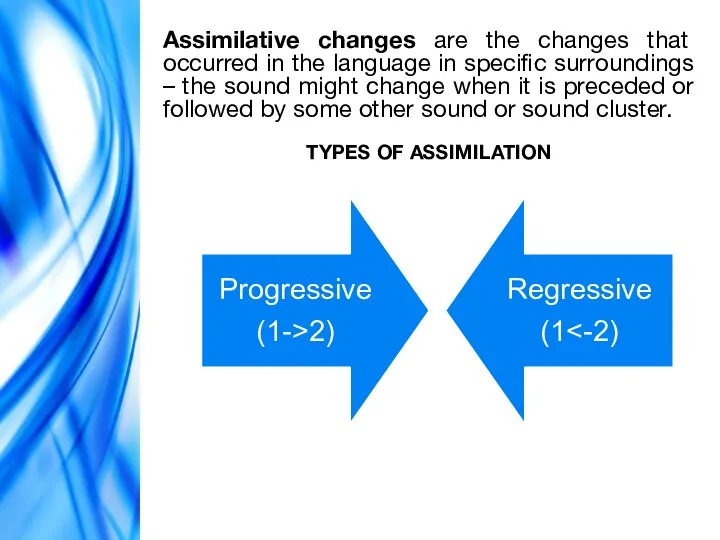

- 35. Assimilative changes are the changes that occurred in the language in specific surroundings – the sound

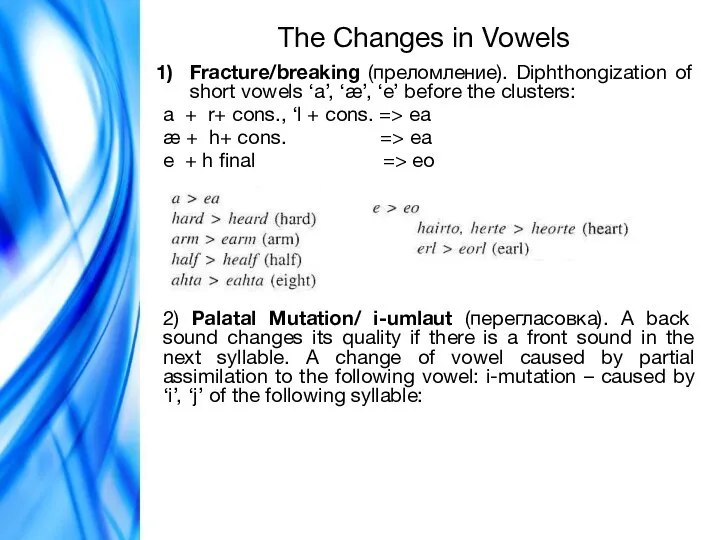

- 36. The Changes in Vowels Fracture/breaking (преломление). Diphthongization of short vowels ‘a’, ‘æ’, ‘e’ before the clusters:

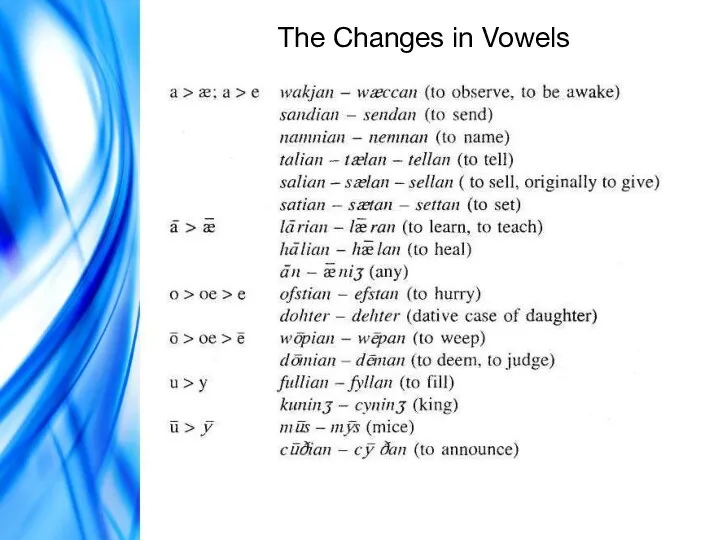

- 37. The Changes in Vowels

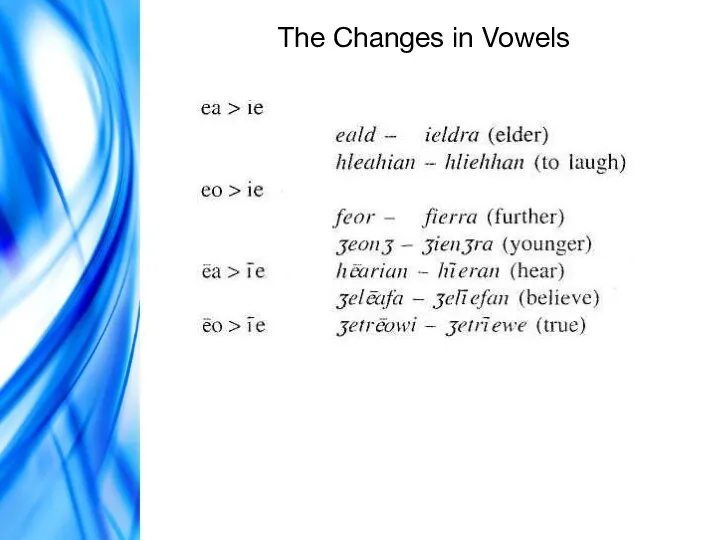

- 38. The Changes in Vowels

- 39. The Changes in Vowels 3) Diphthongization after palatal consonants. Vowels under the influence of the initial

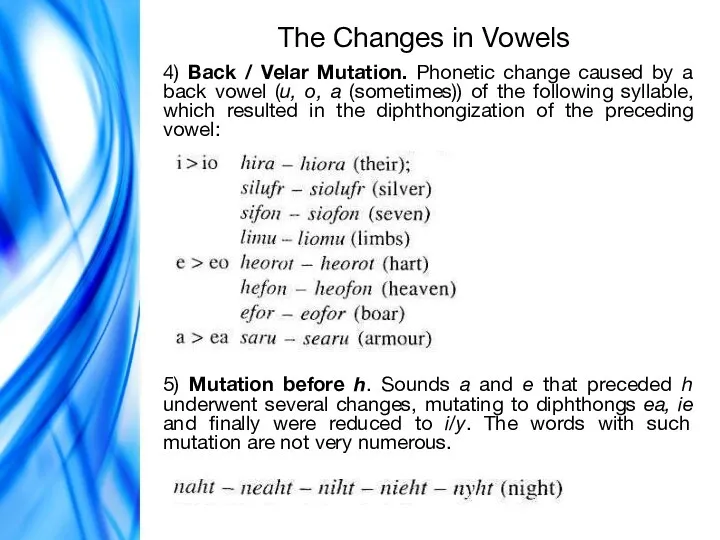

- 40. The Changes in Vowels 4) Back / Velar Mutation. Phonetic change caused by a back vowel

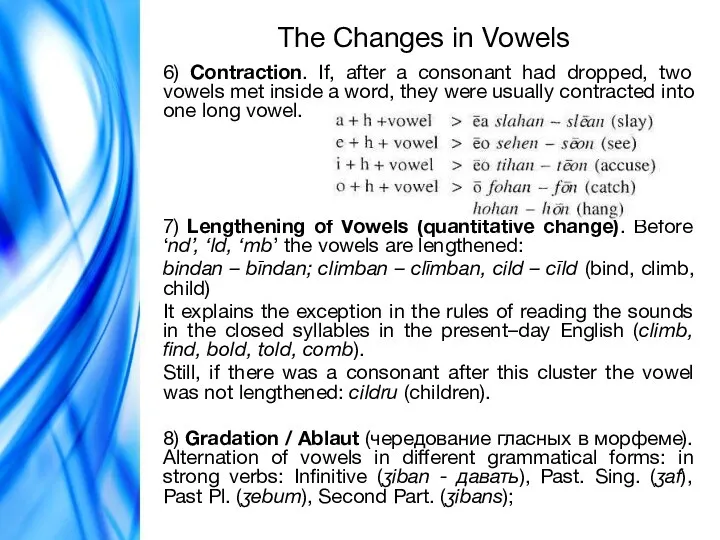

- 41. The Changes in Vowels 6) Contraction. If, after a consonant had dropped, two vowels met inside

- 42. 5. Changes in Consonants.

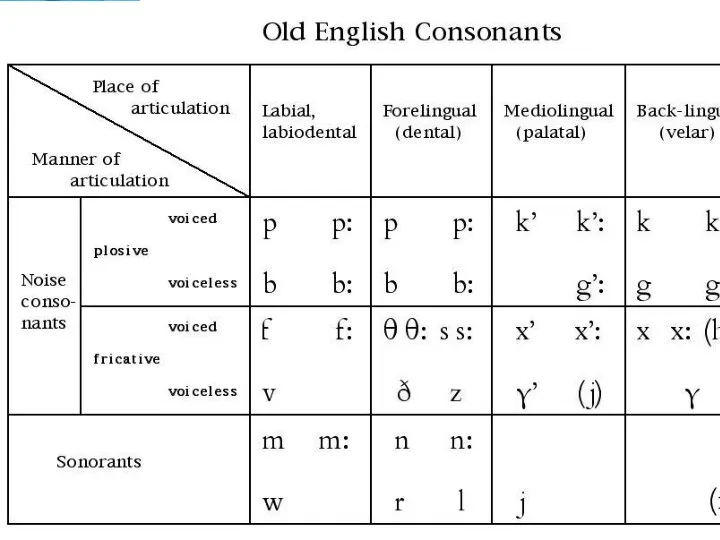

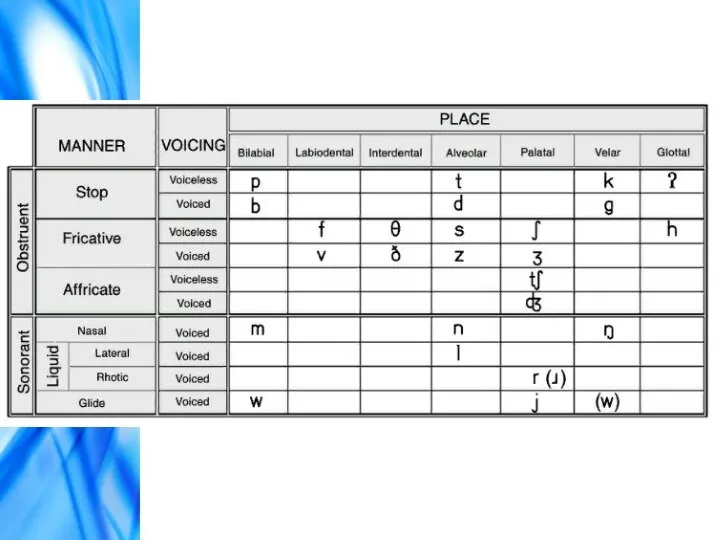

- 43. The System of Consonants in Old English The Old English system of consonants phonemes have changed

- 44. The System of Consonants in Old English

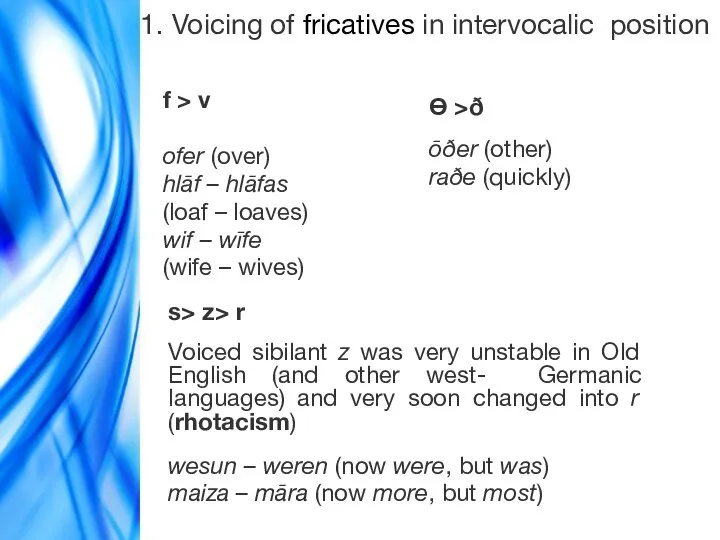

- 47. 1. Voicing of fricatives in intervocalic position f > v ofer (over) hlāf – hlāfas (loaf

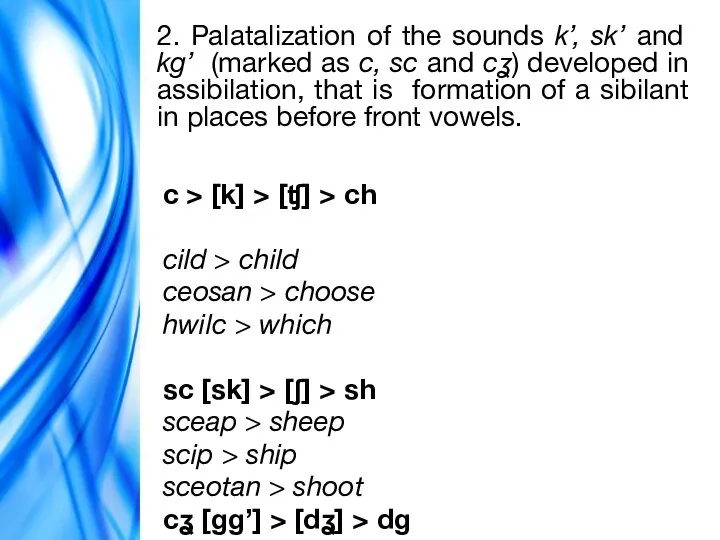

- 48. 2. Palatalization of the sounds k’, sk’ and kg’ (marked as c, sc and cʓ) developed

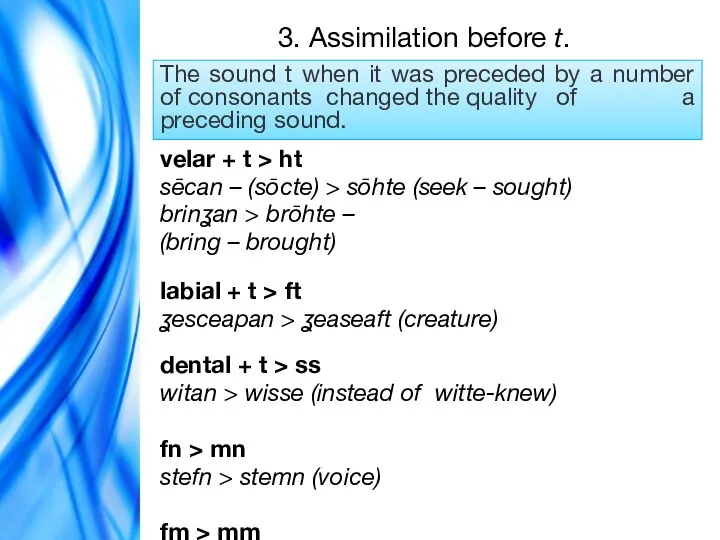

- 49. 3. Assimilation before t. The sound t when it was preceded by a number of consonants

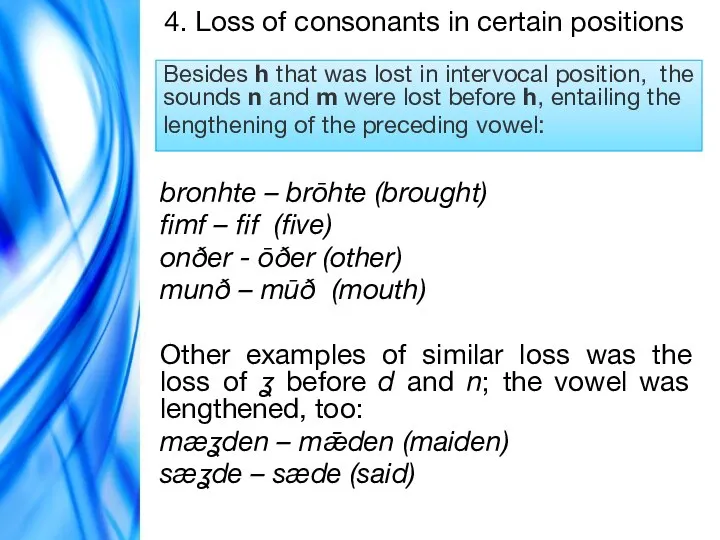

- 50. 4. Loss of consonants in certain positions Besides h that was lost in intervocal position, the

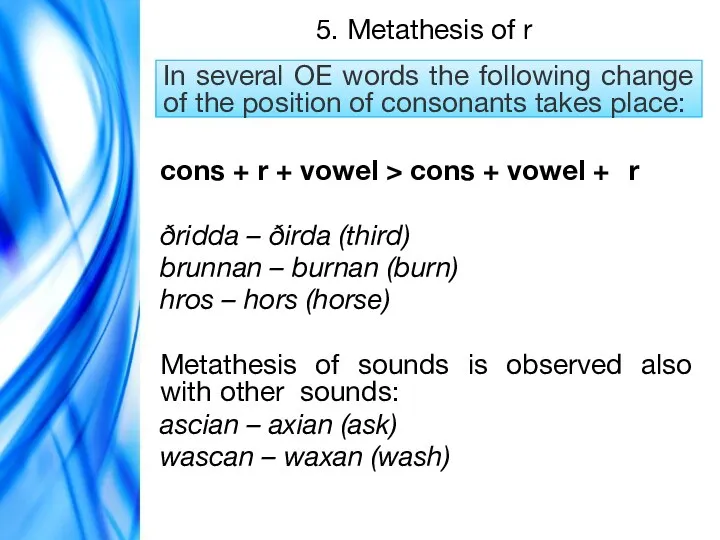

- 51. 5. Metathesis of r In several OE words the following change of the position of consonants

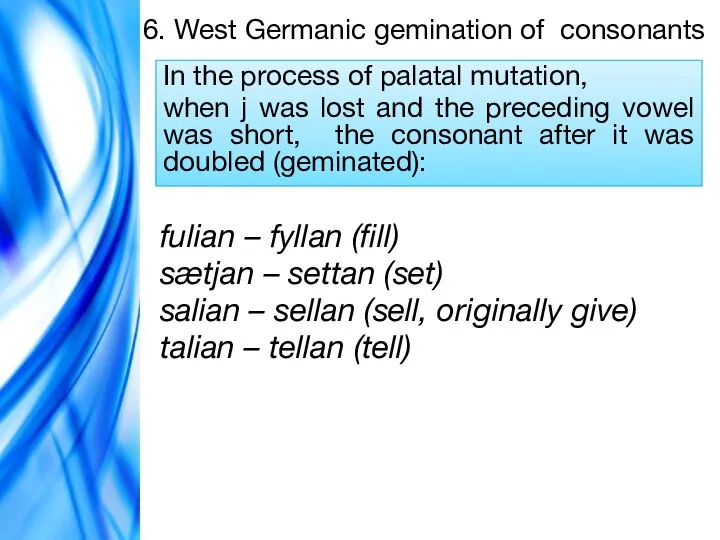

- 52. 6. West Germanic gemination of consonants In the process of palatal mutation, when j was lost

- 54. Скачать презентацию

![9. h [h] hām (home), him (him), huntoð (hunting) 10. i](/_ipx/f_webp&q_80&fit_contain&s_1440x1080/imagesDir/jpg/727281/slide-24.jpg)

Travelling to Учитель английского языка МОУ г.Кургана «Лицей № 12» Романова Н.В.

Travelling to Учитель английского языка МОУ г.Кургана «Лицей № 12» Романова Н.В.  Географические названия Великобритании

Географические названия Великобритании Fruit and Vegetables

Fruit and Vegetables Talking a walk around familiar places

Talking a walk around familiar places Present Perfect Tense

Present Perfect Tense Past Tenses. Continuous

Past Tenses. Continuous Youth organizations in Great Britain Made by: Kyznetsova Katia Form 11 A

Youth organizations in Great Britain Made by: Kyznetsova Katia Form 11 A  Скачать It’s delicious!

Скачать It’s delicious! Trouble shared. 7 класс

Trouble shared. 7 класс This is Bart. Bart is a student

This is Bart. Bart is a student Passive Voice. Пассивный/страдательный залог be + V3 (ed)

Passive Voice. Пассивный/страдательный залог be + V3 (ed) Говорение в ЕГЭ по английскому языку. Типичные ошибки, советы и рекомендации

Говорение в ЕГЭ по английскому языку. Типичные ошибки, советы и рекомендации Презентация к уроку английского языка "Поездка" - скачать

Презентация к уроку английского языка "Поездка" - скачать  The Houses of Parliament in London

The Houses of Parliament in London Get ready Starters

Get ready Starters Las

Las  Предпереводческий анализ текста Составители – д.ф.н., проф. Сулейманова О.А. ст.преп. Беклемешева Н.Н.

Предпереводческий анализ текста Составители – д.ф.н., проф. Сулейманова О.А. ст.преп. Беклемешева Н.Н. Урок английского языка по теме «The British monarchy and a parliamentary democracy” (По учебнику К.И.Кауфман, М.Ю.Кауфман для 8 кл Happy English.ru) Учитель: Корнилова Наталья Геннадьевна МБОУ «ДСОШ №3»

Урок английского языка по теме «The British monarchy and a parliamentary democracy” (По учебнику К.И.Кауфман, М.Ю.Кауфман для 8 кл Happy English.ru) Учитель: Корнилова Наталья Геннадьевна МБОУ «ДСОШ №3»  Презентация к уроку английского языка "The Teddy bear - a symbol of unloneliness" - скачать

Презентация к уроку английского языка "The Teddy bear - a symbol of unloneliness" - скачать  TO BE PAST SIMPLE Френдак Галина Емельяновна, учитель английского языка Копьёвской средней школы

TO BE PAST SIMPLE Френдак Галина Емельяновна, учитель английского языка Копьёвской средней школы Houses around the world

Houses around the world  Презентация к уроку английского языка "Present indefinite (simple) tense" - скачать

Презентация к уроку английского языка "Present indefinite (simple) tense" - скачать  Kharitonova Dasha Form 5”v” School №72 Krasnodar 2009

Kharitonova Dasha Form 5”v” School №72 Krasnodar 2009 Speaking Workshop #8 Modals and tenses

Speaking Workshop #8 Modals and tenses My winter holidays

My winter holidays Familly tree

Familly tree Youth`s problems Выполнил: Ученик 9Д класса лицея «Созвездие» г. Самары Учитель: Злобина Ираида Григорьевна

Youth`s problems Выполнил: Ученик 9Д класса лицея «Созвездие» г. Самары Учитель: Злобина Ираида Григорьевна New words

New words