Содержание

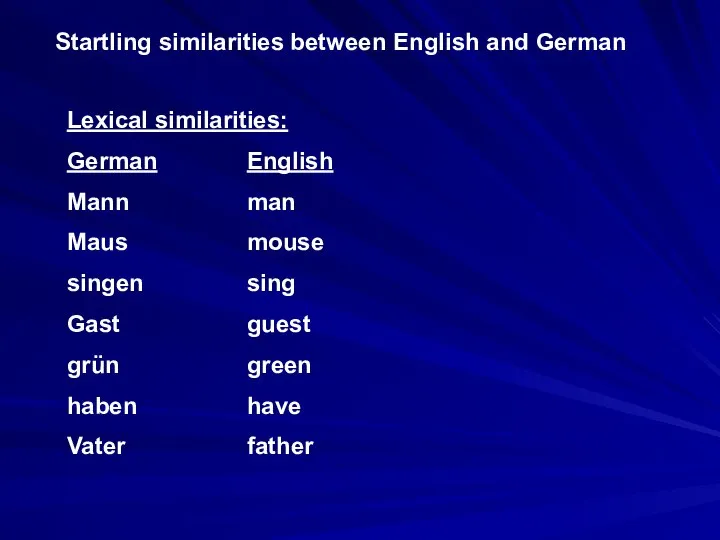

- 2. Startling similarities between English and German Lexical similarities: German English Mann man Maus mouse singen sing

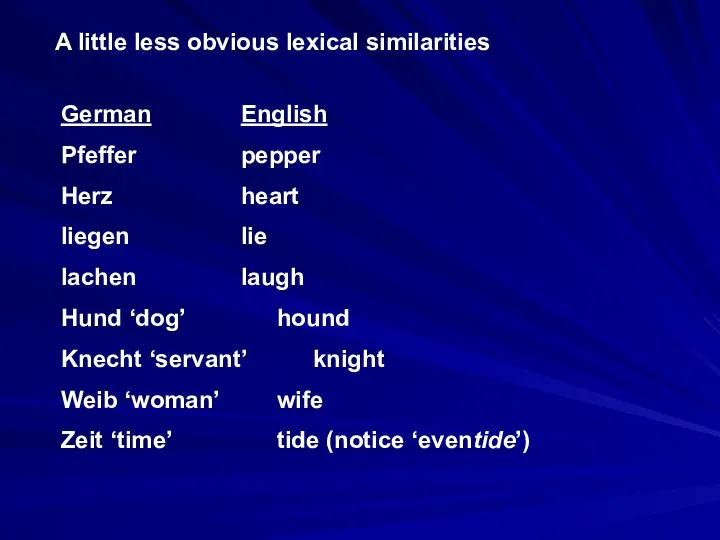

- 3. A little less obvious lexical similarities German English Pfeffer pepper Herz heart liegen lie lachen laugh

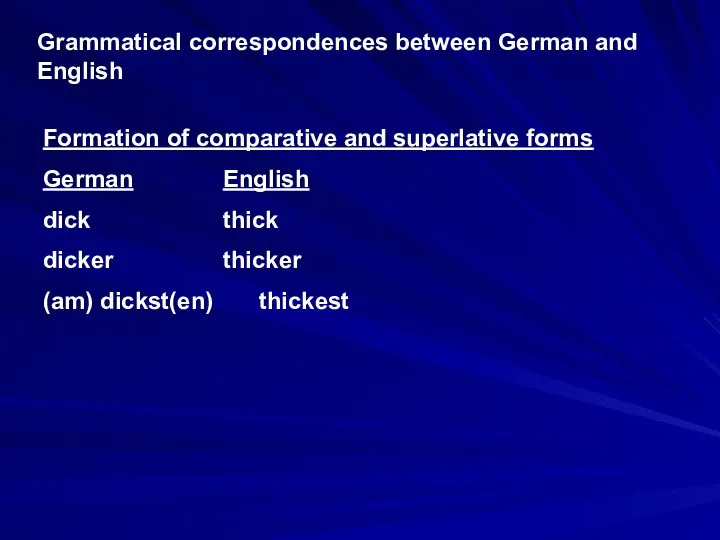

- 4. Grammatical correspondences between German and English Formation of comparative and superlative forms German English dick thick

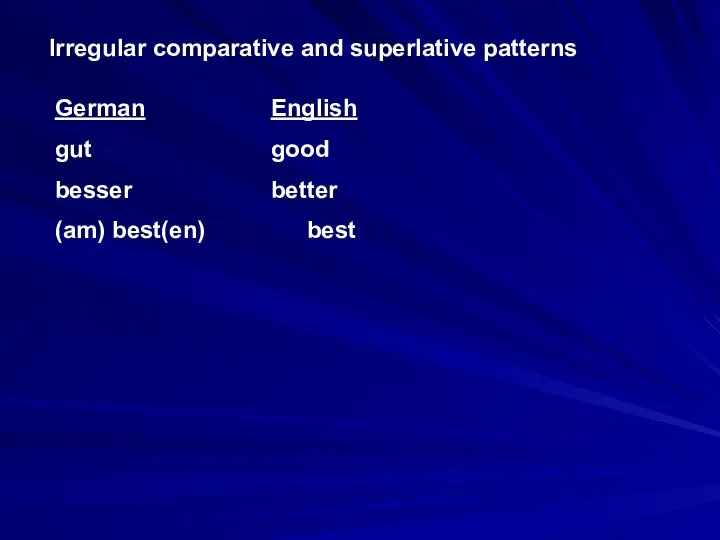

- 5. Irregular comparative and superlative patterns German English gut good besser better (am) best(en) best

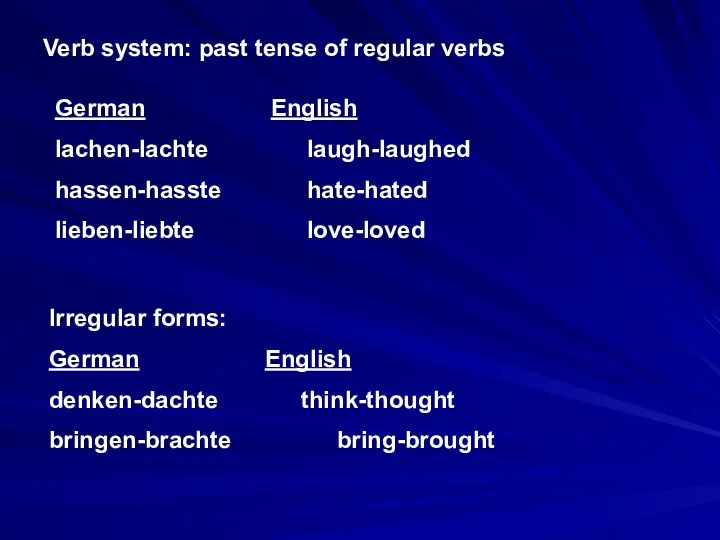

- 6. Verb system: past tense of regular verbs German English lachen-lachte laugh-laughed hassen-hasste hate-hated lieben-liebte love-loved Irregular

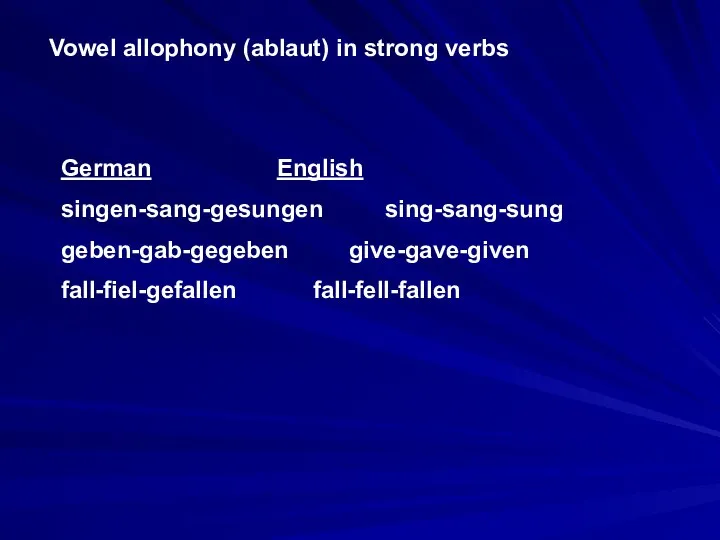

- 7. Vowel allophony (ablaut) in strong verbs German English singen-sang-gesungen sing-sang-sung geben-gab-gegeben give-gave-given fall-fiel-gefallen fall-fell-fallen

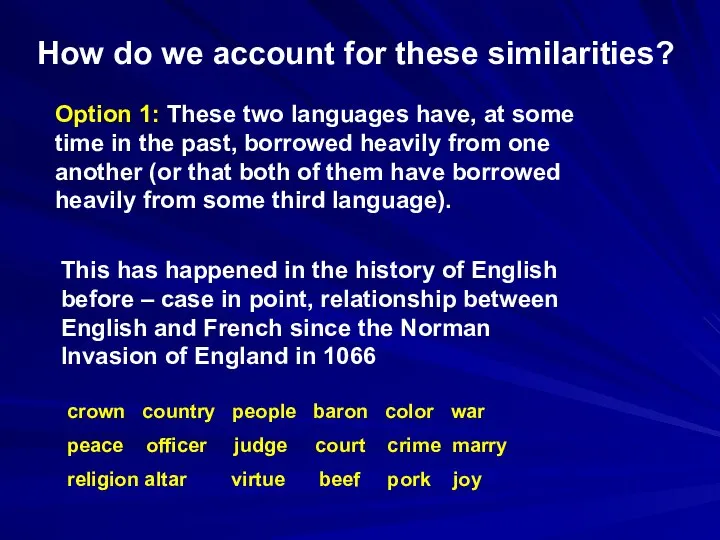

- 8. How do we account for these similarities? Option 1: These two languages have, at some time

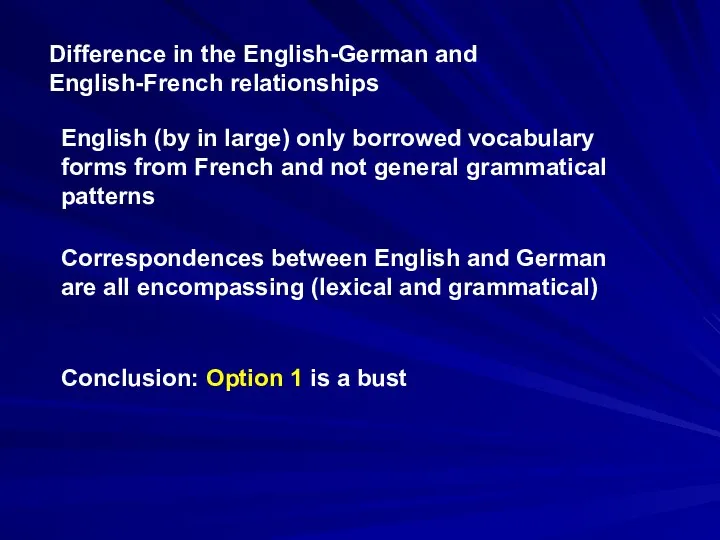

- 9. Difference in the English-German and English-French relationships English (by in large) only borrowed vocabulary forms from

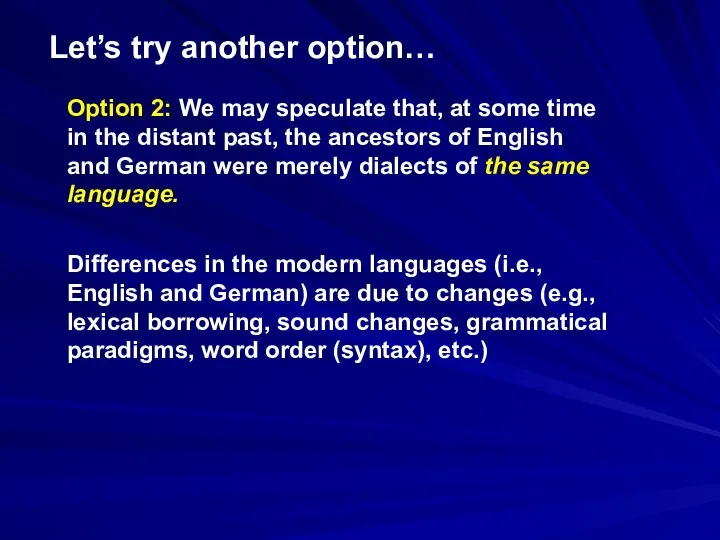

- 10. Let’s try another option… Option 2: We may speculate that, at some time in the distant

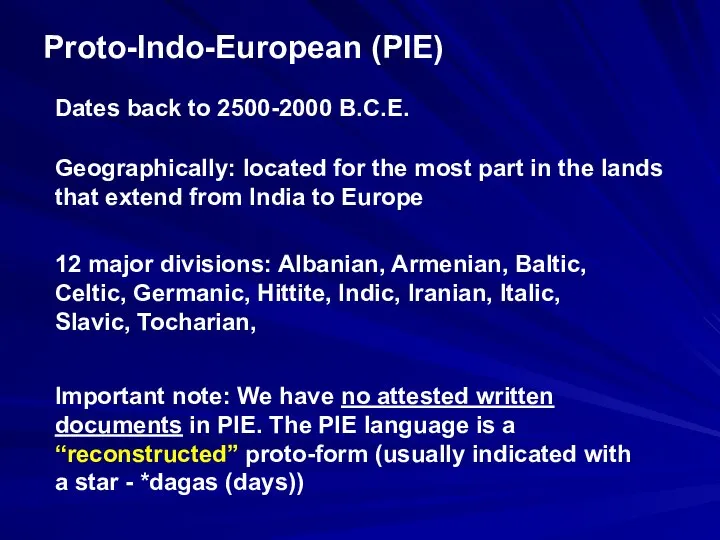

- 11. Proto-Indo-European (PIE) Dates back to 2500-2000 B.C.E. Geographically: located for the most part in the lands

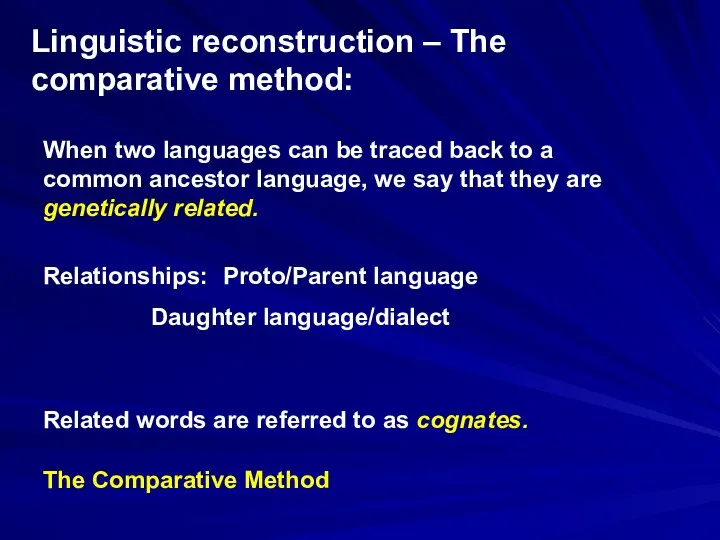

- 12. Linguistic reconstruction – The comparative method: When two languages can be traced back to a common

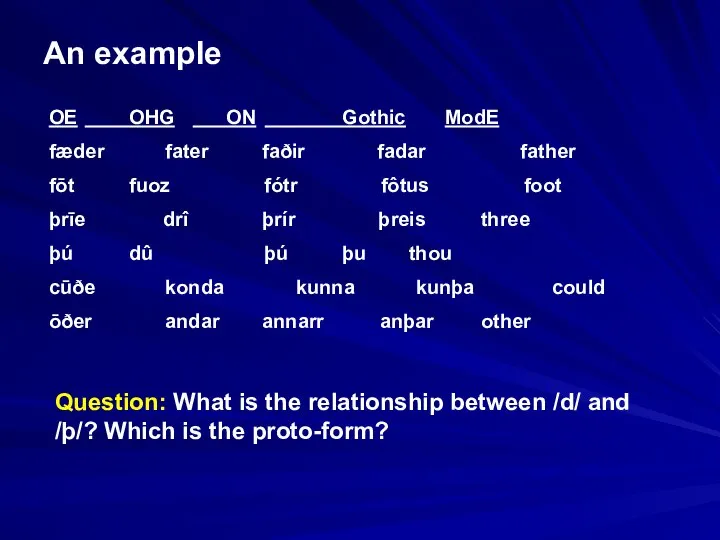

- 13. An example OE OHG ON Gothic ModE fæder fater faðir fadar father fōt fuoz fótr fôtus

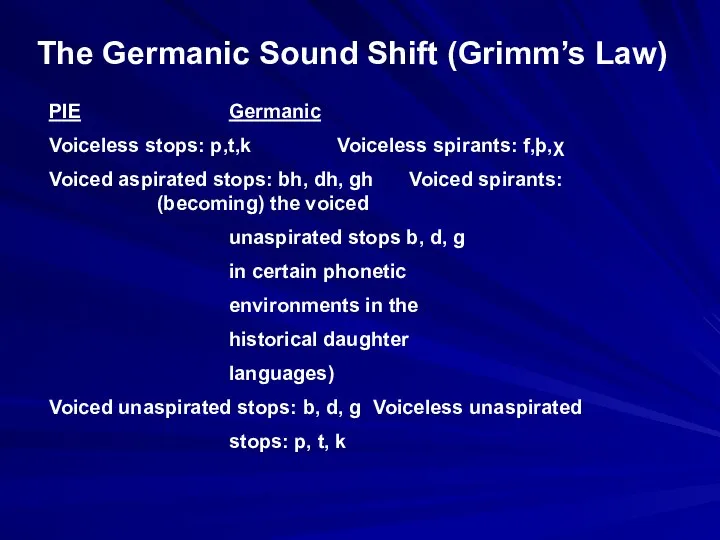

- 14. The Germanic Sound Shift (Grimm’s Law) PIE Germanic Voiceless stops: p,t,k Voiceless spirants: f,þ,χ Voiced aspirated

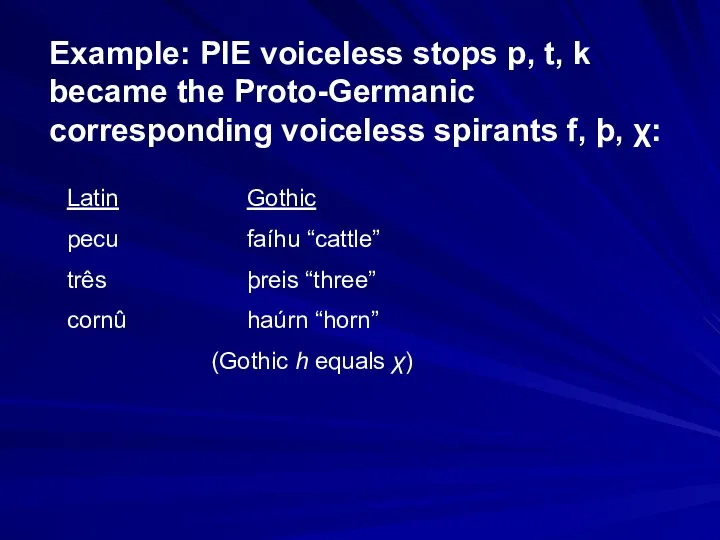

- 15. Example: PIE voiceless stops p, t, k became the Proto-Germanic corresponding voiceless spirants f, þ, χ:

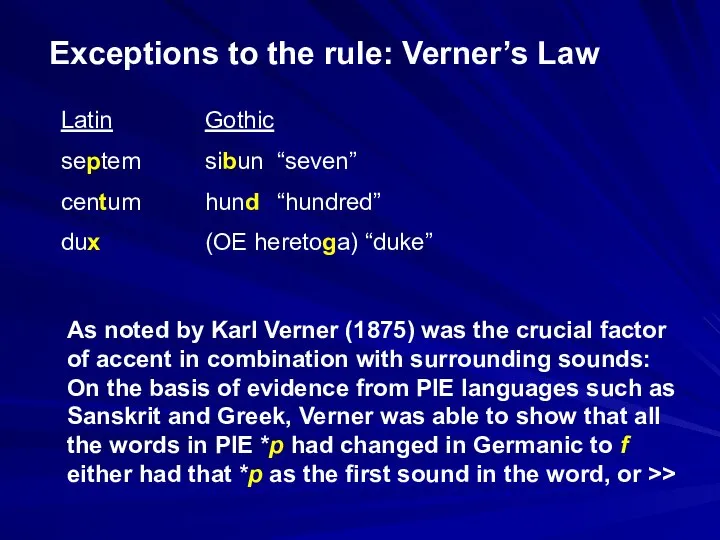

- 16. Exceptions to the rule: Verner’s Law Latin Gothic septem sibun “seven” centum hund “hundred” dux (OE

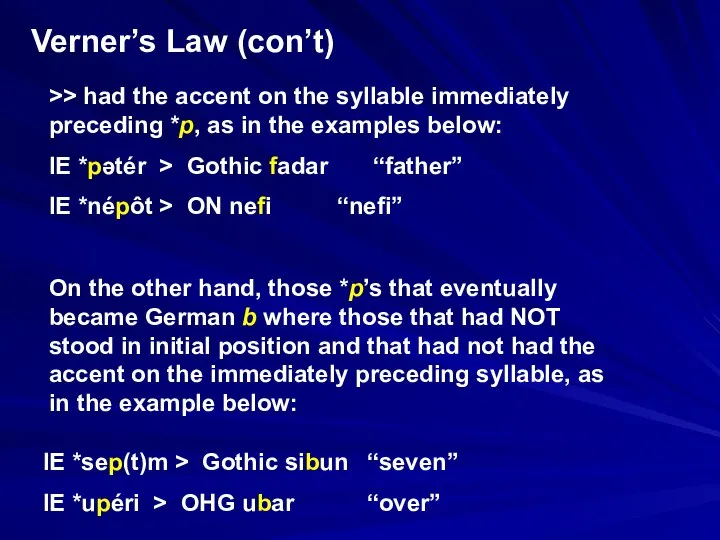

- 17. Verner’s Law (con’t) >> had the accent on the syllable immediately preceding *p, as in the

- 18. Linguistics, Archeology, and History Language groups should never be confused with ethnic groups. The Indo-Europeans appear

- 19. Final notes on the Indo-Europeans Beach tree – If this reconstructed form is correct, then it

- 20. The Germanic Tribes The weight of the evidence points to an ancient homeland in modern Denmark

- 21. Völkerwanderung We may reconstruct a gradual splitting-up of the Germanic people and their languages, along with

- 24. Скачать презентацию

British nature

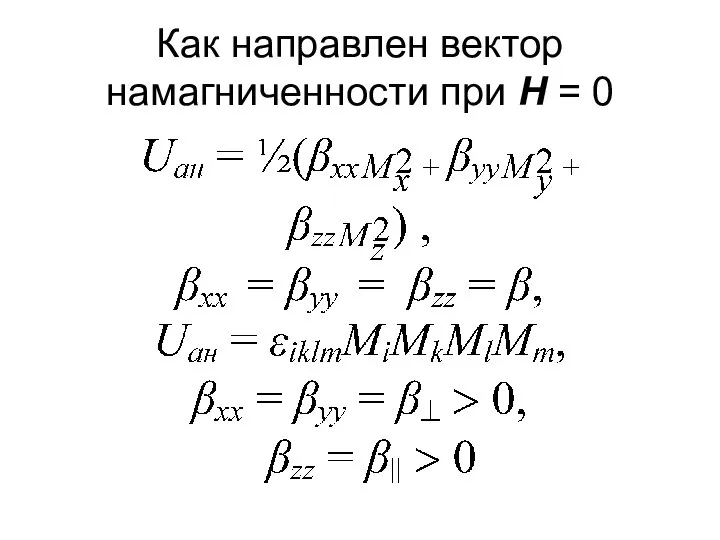

British nature Как направлен вектор намагниченности при Н = 0

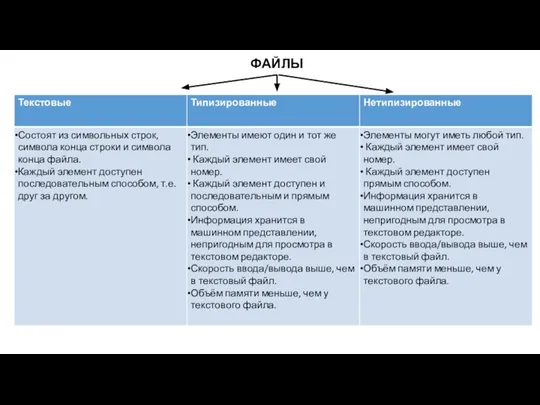

Как направлен вектор намагниченности при Н = 0 Текстовые, типизированные, нетипизированные файлы

Текстовые, типизированные, нетипизированные файлы 小 波 認 知 大 翻 翻 書

小 波 認 知 大 翻 翻 書 Паралимпийский спорт

Паралимпийский спорт Одновимірні масиви. Поняття масиву даних. Види масивів. (Лекція 5)

Одновимірні масиви. Поняття масиву даних. Види масивів. (Лекція 5) Доғалы пісіруге арналған электродтар

Доғалы пісіруге арналған электродтар Достопримечательности Санкт-Петербурга

Достопримечательности Санкт-Петербурга Народная кукла-оберег «Желанница»

Народная кукла-оберег «Желанница» Конвергентные и цифровые технологии

Конвергентные и цифровые технологии Труд как способ удовлетворения человеческих потребностей

Труд как способ удовлетворения человеческих потребностей Спортивная медицина. Неотложные состояния. Доврачебная помощь. Лекция 7

Спортивная медицина. Неотложные состояния. Доврачебная помощь. Лекция 7 Презентация на тему "МЕТОДОЛОГИЧЕСКИЕ ОСНОВЫ ПСИХОЛОГИИ" - скачать презентации по Медицине

Презентация на тему "МЕТОДОЛОГИЧЕСКИЕ ОСНОВЫ ПСИХОЛОГИИ" - скачать презентации по Медицине Безопасность интернет-проекта. Основные угрозы. Инструменты безопасности в платформе

Безопасность интернет-проекта. Основные угрозы. Инструменты безопасности в платформе ЖЕЛЧНОКАМЕННАЯ БОЛЕЗНЬ 7

ЖЕЛЧНОКАМЕННАЯ БОЛЕЗНЬ 7 Влияние занятий по дзюдо на развитие скоростно-силовых качеств у детей среднего школьного возраста

Влияние занятий по дзюдо на развитие скоростно-силовых качеств у детей среднего школьного возраста Структура уголовного законодательства. Уголовно-правовая норма. Действие уголовного законодательства во времени

Структура уголовного законодательства. Уголовно-правовая норма. Действие уголовного законодательства во времени Создание международного центра по разработке и внедрению новых материалов и имплантантов на рынок ортопедических услуг

Создание международного центра по разработке и внедрению новых материалов и имплантантов на рынок ортопедических услуг Налогово-бюджетная система

Налогово-бюджетная система  Реестр недобросовестных поставщиков, органы власти, уполномоченные на ведение реестра

Реестр недобросовестных поставщиков, органы власти, уполномоченные на ведение реестра  5. Фазы лечения.pptx

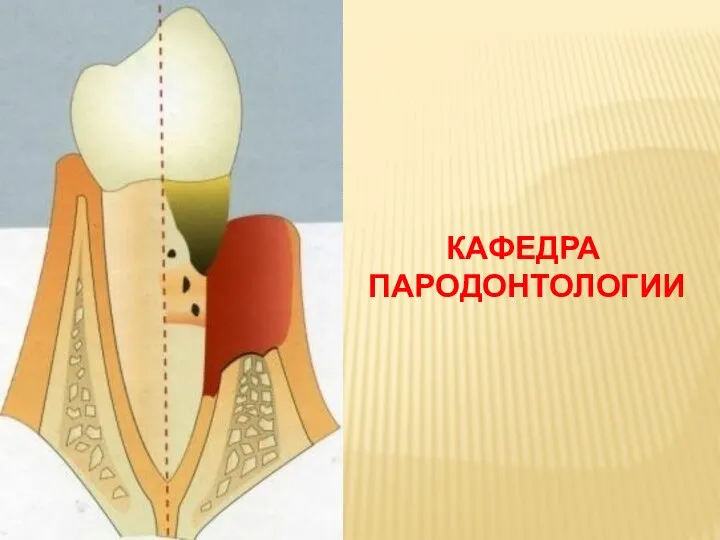

5. Фазы лечения.pptx Четвёртая власть и её роль в политической жизни обществ

Четвёртая власть и её роль в политической жизни обществ Отношение художника к миру вещей

Отношение художника к миру вещей Особенности восприятия изобразительного искусства Выполнила: Накраплённая Е.А.

Особенности восприятия изобразительного искусства Выполнила: Накраплённая Е.А. Тема: «Романтизм в западноевропейской культуре XVIII – XIX вв.» Выполнил: Габибов Тимур Ариф Гаджиев группа Т093

Тема: «Романтизм в западноевропейской культуре XVIII – XIX вв.» Выполнил: Габибов Тимур Ариф Гаджиев группа Т093 Razreshenie_konfliktov_pri_uchastii_posrednikov

Razreshenie_konfliktov_pri_uchastii_posrednikov Победа Дональда Трампа

Победа Дональда Трампа Сергий Радонежский

Сергий Радонежский